Denied access to his parents' funerals, an Inuk inmate is demanding change

After being denied access to his parents' funerals, an Inuk inmate is demanding systemic change.

Johannes Semigak, serving a 3½-year sentence for manslaughter in the death of his brother in November 2020, is set to be released from the Labrador Correctional Centre this fall.

In late May, his father, Gus Semigak, died. In a statement, the Nunatsiavut government called Gus Semigak, a teacher who shared traditional ways with others, a "wealth of knowledge and a true champion for our language and heritage."

Johannes Semigak said his father had a complicated life; he was forcibly relocated from the northern Labrador community of Hebron as a young child and struggled with alcohol use. Despite that, he said, his father was a happy and kind person.

"He was always there for somebody. He was always helping somebody deal when you're down and out, and he was always helping anybody," Semigak said.

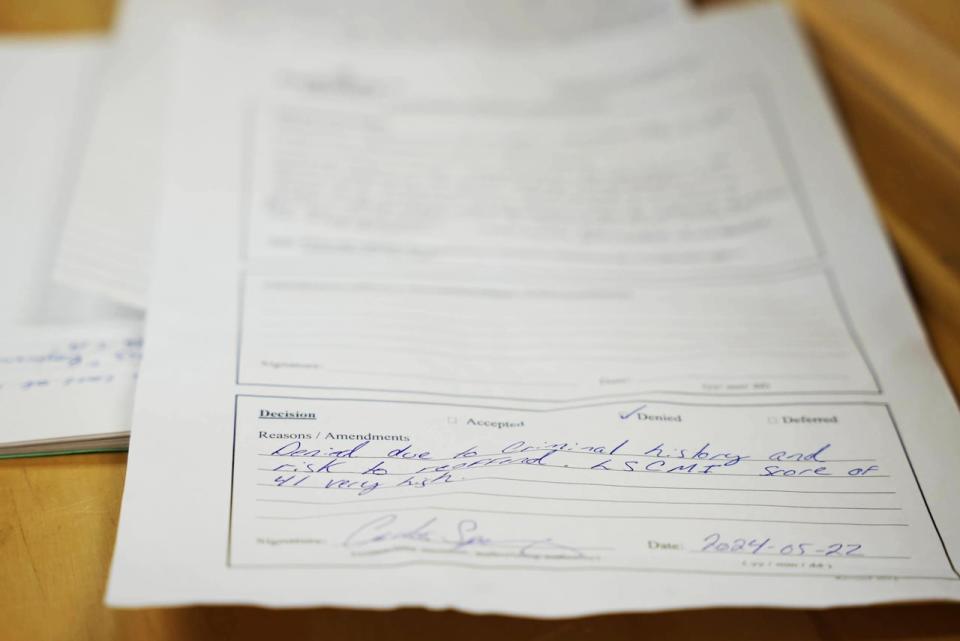

Semigak requested a temporary absence from the prison to attend his father's funeral in Hopedale, but it was denied due to his "criminal history and risk to reoffend," according to the written decision.

Semigak also wasn't permitted to attend his mother's funeral in March 2023. He asked to be escorted from the prison for a day trip to Hopedale for the funeral but was denied due to a staffing shortage.

"Your mom put you in this world," Semigak said. "I never got to say goodbye to my mom. I never got to kiss her on the forehead. What do they expect me to do? Dig up my mom and say goodbye to her? I'm never going to get that back."

Semigak appealed the rejection of his request to go to his father's funeral, asking for a one-day escorted absence. It was also denied. Now he's calling for changes to the process.

"I never got to bury them. I never got to say goodbye proper to them," Semigak said. "It should be mandatory to let an Indigenous person bury their loved ones, especially their mom or dad."

Justice and Public Safety Minister John Hogan said temporary absences can vary from a short escorted visit to a few days away.

The province uses the Level of Service/Case Management Inventory scale, which assigns people a number between one and 50, Hogan said. It considers a number of factors, including a person's criminal history, reason for incarceration, institution record, breaches of orders, risks to the public and prior victims, he said.

The higher a score, the less likely a temporary absence will be granted, Hogan said. Semigak was assigned a score of 41, Hogan said, not enough to allow a temporary absence.

Semigak's family and the Nunatsiavut government advocated for the minister's office to review the request. Hogan said he asked the Labrador Correctional Centre to review the decision. After that review, Hogan said, he's confident the appropriate decision was made. Semigak had a private viewing of his father at the funeral home and attended the funeral virtually, Hogan said.

Deciding whether to grant a temporary absence is a balance between helping a person's rehabilitation and public safety, Hogan said.

"We do need to look at how that rehabilitation can be done," Hogan said. "But the other side of that too is public safety is a priority, and we have to make sure that the public are safe."

Semigak acknowledged he has had a troubled life with a lengthy criminal record. But he has attended treatment and is actively seeking counselling and elder sessions to heal from his past and create a better future.

"I done bad things. Everybody does bad things. They learn from their mistakes. I learn from my mistakes," Semigak said. "I don't know why they denied me for it when I'm trying to, I was doing good in here, past three years."

Erin Broomfield, Nunatsiavut's regional justice services manager, said decisions shouldn't be based only on what she said are Westernized risk assessments.

"I think culture and context needs to be a priority to consider," she said.

The risk assessment needs to consider the different contexts and cultural factors of Indigenous peoples, include consultation with the community and elders, consider whether the community and family wants the absence, and be more transparent, Broomfield said.

The Inuit are a collective, and heal through being together, Broomfield said. Not allowing someone to heal with family after the death of a parent and participate in the cultural practices can cause distress and further harm, hurting their ability to heal, she said.

I was glad to see my dad before he got buried, but it was hard without my sisters. - Johannes Semigak

"If they are incarcerated, it means that they've already experienced traumas and colonial harms. And I think the priority needs to be what can we do to help them heal so that when they're released, they're more healthy," Broomfield said.

Semigak said he was lucky to see his father with a few extended family members at the funeral home in Happy Valley-Goose Bay and watch the funeral live but it wasn't the same as supporting his sisters and children in person when his father was buried in Hopedale.

"It really didn't feel right," Semigaksaid. "I was glad to see my dad before he got buried, but it was hard without my sisters."

If the correctional system truly wants to correct people's behaviour and keep them out of prison, Semigak said, Indigenous protocols and the risk of compounding trauma should be considered.

The situation has been traumatic and has him struggling to resist drinking and returning to his addictions, he said.

"Now I'm thinking like I want to go back to alcohol again because I never got to bury my parents," he said. "But I know I got a strong will to keep my promises to people I want to help."

The justice system isn't helping people, he said.

"It's just making the person worse for when they get out," he said.

Download our free CBC News app to sign up for push alerts for CBC Newfoundland and Labrador. Click here to visit our landing page.