Famed U.K. codebreaking centre to be new College of Cybersecurity

There is an old industrial-looking building in faded hues on the edge of a housing estate in the English town of Milton Keynes. It has broken windowpanes, peeling paint and the blank stare of a past that time seems to have forgotten.

But the derelict walls once throbbed with all the excitement and pressures of wartime Britain. They were — and still are — a part of Bletchley Park, home to the country's famed codebreakers during the Second World War.

Now the building is being called out of retirement, slated to house a brand new generation of codebreakers at the U.K.'s first ever National College of Cybersecurity.

It's long overdue, according to Oscar O'Connor, chief technology officer for Qufaro, a private consortium of cyber-industry experts and advocates driving and funding the project.

"The explosion of the internet means that devices that you wouldn't think of as a potential target area are really very easy to compromise," he said while touring the site of the school due for completion in 2018.

"We have to find new ways of thinking about the implications of what it is we want to do with the technology," he said.

"There are people out there, organized crime networks and nation states, who spend a great deal of money trying to figure out ways to use the stuff we buy for perfectly legitimate purposes — to subvert us, the organizations we work with and the countries we live in."

Prodigies wanted

Tuition will be free and places will be offered to "the U.K.'s most gifted 16- to 19-year-old prodigies," according to Qufaro.

The group says Britain isn't developing enough talent quickly enough to defend against the growing threat of hacking and other forms of cybercrime, from sabotage, to industrial espionage to old-fashioned spying.

They're looking for what they call "raw talent."

"That may be advanced coding skills," says O'Connor. "It may be cryptography, it may be behaviour — you know, that they can intrinsically think like an adversary. And we need all of those skills."

Qufaro clearly hopes placing the school at Bletchley Park will put it on the map, marrying a storied past with what the consortium promises will be a "pioneering security technology centre."

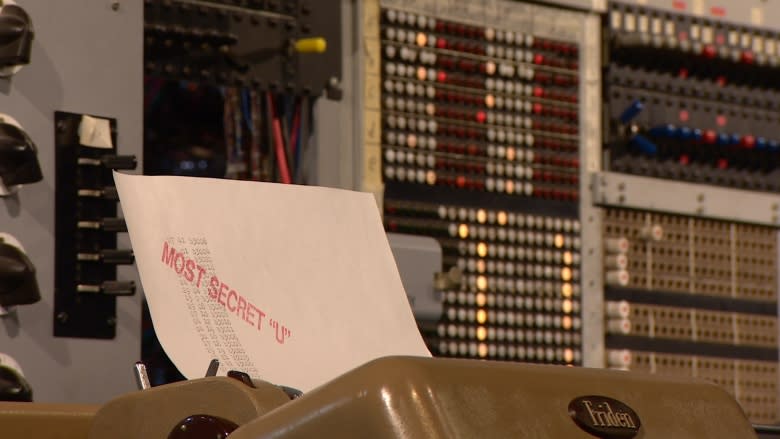

G Block, as the crumbling building was known during the war, was the section of the top-secret facility devoted to breaking codes intercepted from Nazi Germany's high command. Mathematician Alan Turing led a team that cracked the German Enigma code.

"It was actually in this building where the first messages were decrypted that told us about the Holocaust," said O'Connor.

Britain's National Museum of Computing is also on the Bletchley site. That's where you can catch a glimpse of "Colossus" — or at least a replica of the original, which the museum says was the world's first electronic, semi-programmable computer, created by the Bletchley team during the war.

Margaret Sale, a trustee at the museum and a member of Qufaro, sees a link between the original cryptographers at Bletchley and the type of students the new cyber college wants to attract.

"They were rather special," she says of the wartime generation of codebreakers. "What we're aiming for with G Block, in fact, is to pick out the youngsters with extra talents, the people who don't just take things at face value."

'James Bond moment'

Few Brits knew that Bletchley Park even existed until the 1970s because of secrecy laws.

Mary Every, now in her 90s, was recruited by British intelligence to work at Bletchley as a young woman.

One of her first assignments was to turn up at a Soho wine shop in London with a code word.

She calls it her only real "James Bond moment." When she delivered the word, she says, she was taken to a room upstairs.

"There was a senior RAF officer sitting there, behind a desk," she said. "And on the desk were a series of coloured telephones. Well, in those days, I had never seen a coloured telephone; they were always black. And he was talking on two, in two different languages!"

Every was then sent on a crash course to learn Japanese before arriving at Bletchley Park to work on messages intercepted from Germany's ally, Japan.

"I mean, I could tell you how to bomb an airfield, but I couldn't tell you how to have a cup of tea," she jokes.

Every isn't a fan of the internet, saying it compromises security on all levels. She worries about the lack of government involvement in the planned college. And, unlike Margaret Sale, she doesn't see a link between herself and the potential codebreakers of today.

"I mean, I don't even recognize how some of them think," she said. "It's such a different world, it's impossible for you to realize what the world that I grew up in was like."

But the new cyber school's backers say placing the college at Bletchley Park will help bridge that gap.

They also say the talent pool they create will benefit government and industry alike, preparing students for the workforce or university-level studies.

Wartime Bletchley was originally run by the government's Code and Cypher School, which evolved into what is today Britain's Government Communications Headquarters or GCHQ, another spy agency.

"The concept ... is interesting, especially if it can provide a pathway for talented students from schools that are not able to provide the support they need," GCHQ said in a statement about the college. "We wish Qufaro well in the endeavor."

The guardians of the Bletchley memory, like Every and Sale, are wishing it well, too, hoping that it will remind people of just how advanced — and how critical to winning the war — Britain's codebreakers were.

Much rather that than a faded building lost in cobwebs and sinking under the weight of time.

A look to the future, with a nod to the past.