In governor’s race, a test of the life (or death) of ‘old school’ campaigns in a sea of ads

Just over 20 people gathered in the small Robertson County Community Center and Volunteer Fire Department building on an April morning, a sizable chunk of the county, Kentucky’s lowest in population at 2,193.

They came to hear Ryan Quarles, the Republican state commissioner of agriculture, speak about his campaign for governor.

Sue Green, shopkeeper at an open-once-weekly downtown Mt. Olivet (pop: 347) store called the Jun’Q Stop, rose to comment that she liked Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear. But she thought she’d support Quarles because he was the only state politician she recalled stopping in Robertson County.

“If you make governor, are you gonna forget this day ever happened? Are you gonna forget about Robertson County,” Green asked.

“No,” Quarles said immediately. “I’m going to remember the folks who took me.”

The moment played out like a scene in the most romanticized version of the Quarles campaign.

At every turn, Quarles has gone out of his way to brand his campaign as the one with the most “grassroots” energy, old school charm and rural appeal as the “jeans and boots” candidate that looks out for the oft-forgotten communities like Robertson County. As evidence, his campaign often touts the 235-plus local elected official endorsements its collected – a far greater number than any other campaign.

There’s some truth to the Quarles campaign’s branding. The 39-year-old commissioner has had as much or more time to travel the state and make political connections than any other major contender.

Scott Jennings, a former top staffer for U.S. Senator Mitch McConnell who’s become perhaps the chief Kentucky Republican political representative for national media, has made the point many times over: this race is less about policy differences between the top three “mainstream conservative Republicans” than it is their varying political approaches.

And so far, the approaches of Attorney General Daniel Cameron and former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Kelly Craft have put them above Quarles in the lead-up to the race.

Cameron has consistently built a celebrity profile within the state given his status as the first Black attorney general, a pro-Trump speech at the Republican National Convention and his handling of an investigation following the police killing of Breonna Taylor.

Craft, who has loaned herself more than $9 million so far, has been on television consistently since January. She’s carved out issue-based lanes on matters of national and statewide importance.

The last publicly available poll, conducted in mid-April as Cameron was just beginning to get up on television and before Quarles had done so, Cameron garnered 30% of the vote to Craft’s 24% and Quarles’ 15%.

What separates Quarles’ campaign from that of the other ‘top three’ candidates is a bet: that “old school” campaigns can work statewide, and that local political machines still matter. They could matter even more with a predicted low turnout, he added.

“I believe that many elected officials are influencers back home in their county, and even in their district within the county. Magistrates know where the votes are at. We’re happy to aggressively pursue as many endorsements as possible – it’s a reflection of our grassroots campaign,” Quarles said.

But politics is shifting in a direction away from Quarles’ strategy and towards Craft and Cameron’s media-heavy approaches. In many places throughout the state, particularly urban and suburban areas, voters know less about who their local officials are, let alone who they’re supporting for governor. The question, though, is how quickly that’s changing.

Strategies may vary

Though Quarles’ campaign is betting on local connections, they’re still playing the television game. But make no mistake: that’s a game Craft, and to some extent Cameron, are winning.

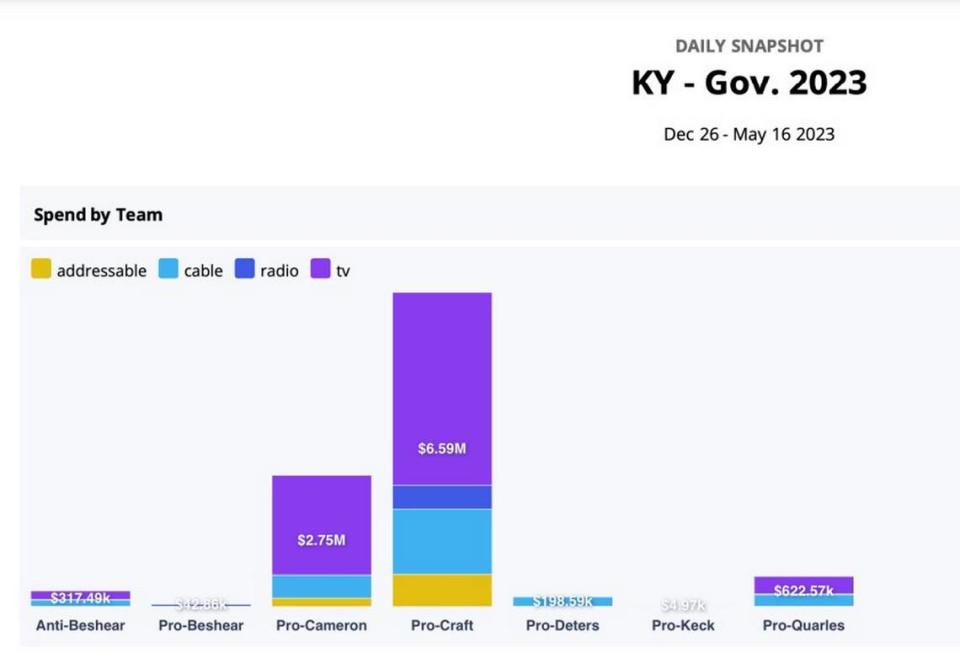

Craft’s $6.6 million documented ad spending, according to Medium Buying, dwarfs all other competitors. Craft and a political action committee (PAC) formed to support her have spent more than half of the totals spent this cycle on cable television, local broadcast television, direct mail and radio advertising.

She has aired more television ads in every single media market across the state, as well. Her ads outpace the competition especially in smaller markets and ones that bleed into other states. No other candidates have made significant television investments in the Kentucky-serving markets of Paducah; Cincinnati, Ohio; or Evansville, Indiana. Craft has made six-figure buys in all three. In Cincinnati, the campaign and PAC have spent more than $810,000. Northern Kentucky firebrand conservative activist Eric Deters has spent the second most there, dropping $29,000 on cable ads there.

One potential ace in the hole for Craft against Quarles is his predecessor. Former commissioner of agriculture turned conservative television staple U.S. Rep. James Comer, R-KY, does not like Quarles, though neither official will say why. Comer had the backing of many local officials, and many agriculture folks, in his narrow loss to former governor Matt Bevin in the 2015 GOP primary.

Now Comer is helping Craft barnstorm the state, campaigning alongside her in her South-Central and West Kentucky district. Many Comer-aligned local politicians are now backing Craft as well.

And Craft has a few other nationally prominent figures backing her, including U.S. Senator Ted Cruz, R-Texas, who is a client of the same consulting group — Axiom Strategies — that Craft is using. Cruz is set to attend Craft rallies in the Louisville and Lexington area the weekend before the election.

GOP presidential nominee Vivek Ramaswamy, who started the year as a relative unknown but has risen in the field per some polling, is also backing Craft. Craft has the support of former colleague Mike Pompeo, who served as secretary of state under Trump, too.

Both Cameron and Craft’s campaigns have garnered much more media attention than Quarles, both local and statewide. The two have made appearances on popular conservative Fox News talk show The Ingraham Angle, whose host said the primary race was “largely coming down” to the two of them.

Cameron’s strength comes mostly in his celebrity status and the popularity of his biggest endorsement: Trump.

That means a lot across the state, which Trump carried by 30 points in 2016 and 26 percentage points in 2020.

Harlan County Judge-Executive Dan Mosley said he’s been impressed by how many people he’s run into who have met Quarles, valuing in-person interactions over televised ones, but still thinks Trump’s popularity in his native Eastern Kentucky is a huge factor that helps Cameron.

“If you’re a candidate out there and you’re trying to decide whether you want Donald Trump to endorse you or Dan Mosley, I would encourage you to get Donald Trump to endorse you,” Mosley joked.

In terms of spending, the key difference between Craft and Cameron is that Craft got up on television much earlier. Since getting on air in April, Cameron’s team and a PAC supporting him have largely kept pace with Craft in the main media markets of Lexington and Louisville, where they’ve spent $656,000 and $1.5 million, respectively.

Cameron’s PAC, Bluegrass Freedom Action, has received more money — most of it via untraceable ‘dark money’ — than Craft’s PAC, which has been largely funded by Craft’s husband, billionaire coal magnate Joe Craft. In its ads,Bluegrass Freedom Action has worked hard to remind voters through direct mail and television ads that Trump supports Cameron over Craft.

Looks like Bluegrass Freedom Action is up with another Trump-centric ad supporting Daniel Cameron for #kygov. BFA says this one is only up in Eastern KY, where Trump is generally quite popular. pic.twitter.com/CDeA9R90DL

— Austin Horn (@_AustinHorn) May 5, 2023

There’s some tension there, as Cameron has throughout his political career been branded as a “protege” of U.S. Senator Mitch McConnell, who has been linked to the same dark money group funding the pro-Cameron PAC. Trump and McConnell notoriously do not like each other, in a battle between Trump’s “anti-establishment” attitude and McConnell’s long tenure and strong presence in the U.S. Senate.

That’s a tension that the Craft campaign perhaps tried to get at in placing Cameron and McConnell together in the same frame in a negative light.

But some Cameron supporters are fine with not liking McConnell — a recent poll showed that he’s the least liked Senator in the U.S. — and backing Cameron.

Prominent Northern Kentucky GOP attorney Chris Wiest is supporting Cameron for governor in a notable move for someone who considers himself anti-establishment. Wiest – who claims that McConnell “did not want (Cameron) to run for governor” – says that Cameron’s McConnell ties are apparent, but that he believes Cameron is his own man.

“It doesn’t mean Daniel isn’t going to take a call from Senator McConnell, but I know Daniel is going to take a call from Chris Wiest,” Wiest said.

A ‘laboratory-style experiment’

Not all elected officials, including those supporting Quarles, put as much stock as Quarles does in the power of their opinions.

Bill Bartleman, a McCracken county commissioner – the equivalent of a magistrate in most Kentucky counties – and former political reporter for the Paducah Sun, is supporting Quarles because he thinks he’d look out for West Kentucky.

Bartleman recalled the days when, in McCracken County, the word of figures like the local Democratic party chair could easily sway a primary election. However, this year he hasn’t bothered going public with an endorsement yet because he’s not convinced it matters.

“I’m not sure that my endorsement would help him get more than two votes. You might get mine, my wife’s, and maybe my mother-in-law’s,” Bartleman said.

But longtime Kentucky political operative and Quarles supporter Tres Watson thinks that there’s a chance local politics still matter – that rallying local elected officials, focusing on local issues, and engaging small rural – enough to carry a statewide race.

Watson called this election a “laboratory-style experiment.”

“If you wanted to run a test on (former U.S. House speaker) Tip O’Neill’s saying ‘all politics is local,’ you’re not gonna get much of a better laboratory-style experiment here. Craft and Cameron are hyper-focused on national issues and Ryan is much more focused on the local stuff,” Watson said.

The results of the GOP primary — whether or not Quarles is competitive with the current “top two” — could prove that O’Neill’s famous words still ring true. Or they could prove Bartleman right.

Does it fit today’s politics?

Veteran Kentucky political observer Al Cross said that Grayson County used to be one of several places where local kingmakers reigned supreme in “carrying” a place.

“There’s a retired circuit judge there named Kenneth Goff – he’s 95 years old. He used to be the kingmaker of the county, sometimes he would wait until Sunday afternoon before the election to get in his pickup truck and drive around to all his contacts and say ‘we’re going this way.’ And Kenneth Goff won a lot more than he lost,” Cross said. “You don’t see that happening in rural Kentucky anymore, I don’t think.”

And it’s definitely not happening in the largely suburban Northern Kentucky, per Wiest, who shared to his large Facebook following a lengthy endorsement of the attorney general.

“Do I think (local endorsements) are decisive? No, I don’t. So I think that all politics are at some level relational in that, if somebody that you know vouches for somebody then that has an effect? Yeah,” Wiest said.

Wiest’s post got more than 100 shares.

Boyle County GOP chair Tome Tye, who is neutral in the governor’s race, said that part of the equation could be the decline of local media. That leaves voters to be influenced by social media figures like Wiest, along with nationally-driven news networks.

“The local newspaper here is only two days a week, the morning show on the radio is pretty decent, but outside of social media there really isn’t a lot of local news. I think it does diminish the role (of elected official endorsements), unless they adapt and move to social media,” Tye said.

But perhaps politicians can still carry some “influencer” weight themselves.

Several of the 230-plus local officials that Quarles has collected have posted about their endorsements of the commissioner on Facebook, with many like Rep. Michael Meredith, R-Oakland, who recently sponsored a bill legalizing sports betting in the state, reminding their followers of their support several times.

Somerset Mayor Alan Keck is another candidate for the GOP nomination. Seen as a longshot by some, the statewide political newcomer has tried to utilize social media to a great extent in his campaign, hosting live Q&A sessions and running ads on the platform. He says the era of local official endorsements mattering a lot to voters has largely passed in his native Pulaski County.

“I think there’s a generation of people who are sick of being told who to vote by an elected official… And a state rep, at the end of the day, is probably not going to put in the work that a 22-year-old college student who supports you and really believes in you, is gonna do,” Keck said.

That’s the question for Cross as well as University of Kentucky political science professor Stephen Voss, who studies voter behavior: an endorser putting their name on a list is much different than working to advocate for their preferred candidate.

“Endorsements, in and of themselves, don’t matter very much,” Voss said. “Voters are more likely to take cues from co-workers, family members and interest groups. So you need more than the endorsement – it needs to mean that their networks mobilize on behalf of the candidate they endorse.”

Grigson said she believes that a “word of mouth” campaign fueled by supporters like herself could push Quarles over the top among Robertson County’s 559 — the lowest total in the state, though that figure is more than double what it was in 2015 during the last contested primary.

The number of Republicans in Harlan County almost doubled in that eight-year span, 5,506 to 10,634. Mosley, whose flip from Democrat to Republican in 2021 helped spur the trend, said “it’s a different Harlan County now.”

“The local officials don’t miss a vote, and the people that respect them, they’re asking ‘who’re you for’ and why you’re for them. I think the low turnout is the key. These people, particularly in the rural parts of the state, their families are going to go vote... I don’t think it guarantees that someone’s going to win Harlan County because I’m for him, but the people in my circle are probably going to vote my way,” Mosley said.

A farm base?

Having a political base in an industry – in Quarles’ case, agriculture – is another selling point for his viability on May 16. He highlights the fact that many farmers in East, West and Central Kentucky used to be Democrats until recently, shifting the GOP electorate in his favor.

Among the fastest growing Republican voter bases are counties with agricultural identities. Shelby, McCracken, Greenup and Quarles’ home of Scott County all grew their GOP voter count by at least 47%, according to data from the State Board of Elections. Of the top 30 GOP counties, only Madison and Pike counties posted similar growth rates.

But are farmers really for Quarles?

The answers from voters at Rip’s Farm Center, a staple in Lewis County’s Tollesboro community, varied.

Quarles popped in not for the farm supplies, but for an annual customer appreciation day. Free lunch was served, so that meant lots of potential voters.

The farmers gathered at Rip’s represent the Eastern wing of what Quarles claims is his “farm base.”

Mike Savey and Ronnie Lowe are cattle ranchers close by. They said Quarles’ identity as the farmer candidate plays a huge role in their support for him, not swayed by Craft, referred to as “that lady.”

“Ryan’s a good guy, he’s a farmer, he wears boots and not tennis shoes” Lowe said. “I don’t really know the others, to be honest. Every time I turn the TV on that lady’s on there, but I don’t really know where she is (on the issues).”

One part of Craft-aligned messaging worked with Mason County cattle ranchers Garnet and Shelby Trimble: negative ads hitting Cameron.

“His platform, I cannot stand behind,” Shelby Garnet said, without naming specifics.

Being drawn to Quarles’ agriculture background, he said, “I can stand behind Ryan’s platform.”

However, the farming community is no monolith.

Mary Newell runs a corn and soybean farm with her husband in Mason County. Newell said she’s for Deters. She’s drawn to authentic politicians, and added that she believes Deters shares her negative opinions about COVID-19 lockdowns and

“He’s kind of like my personality: out there and extreme. I’m just gonna be me,” Newell said.

What if it’s not working?

After the stop at Rip’s Farm Center, Quarles held a meet and greet in the dreary gray of early April under a pavilion at the Tollesboro Lions Club Community Park.

Only six non-campaign people showed up.

It stood in contrast to events hosted by Craft, a fellow Central Kentucky resident whose “Kitchen Table” tour has drawn several dozen in the past. Some events for Cameron have also garnered huge crowds.

Quarles spent his time with those who showed up, most of whom were elected officials or very plugged in politicos, instructing them on how to be effective “vouchers” for his campaign.

He asked them to post a photo of themselves with him leading up to election day, to put a road sign and to actively persuade others in the area to vote for Quarles.

“You all are the community connectors in Lewis County. It’s inevitable that the conversation about the governor’s race is going to come up, so please just say ‘hey, I’m supporting Ryan Quarles, and here’s why: he shows up in Lewis County.’”

If they don’t do that, the six in attendance might amount to just six votes.