Grandson of Dayton Boots founder among dozens of workers owed money in gift card wage dispute

The grandson of the man who founded Vancouver's Dayton Boots is one of dozens of employees still owed money after a B.C. Employment Standards Tribunal found the company had paid workers in Dayton gift cards instead of money.

Ray Wohlford doesn't know what his cut is of the almost-$500,000 decision, but says the ruling is a black eye on the once-proud company.

"It's just too bad that this particular thing is dragging the Dayton name down," said Wohlford.

The dispute started when two confidential complaints were filed with the B.C. Employment Standards Branch in October 2020. Both alleged Dayton Boots was deducting 50 per cent of worker wages and "repaying" the amount with gift cards.

An investigation by the Employment Standards Tribunal found Dayton Boots Company Ltd. and sole director Eric Hutchingame were in breach of the Employment Standards Act, which says wages must be paid in Canadian currency and prohibits unauthorized deductions.

On appeal, the determination of the amount owed to workers was reduced by over $100,000. Dayton was ordered to pay $484,995, with Hutchingame's personal liability adjusted to $446,472.

An application to reconsider the appeal decision was denied in November 2022.

'Obvious accounting errors'

In a statement to CBC, Hutchingame said he disagrees with the determination and will continue to fight it.

"...Of the remaining balance almost all of the amounts claimed are the result of obvious accounting errors," he said. "Accordingly Dayton will continue to seek all possible legal remedies."

The determination has been filed as an order in B.C. Supreme Court and it's unclear how Hutchingame will continue to contest it with the tribunal process exhausted.

Documents from the decisions paint a picture of a company with serious difficulty keeping accurate payroll and employment records. In one submission, a former Dayton employee said he only ever received gift cards totalling $3,000, yet the 2020 T4 from the company said he was paid $34,200.

The original determination named 71 employees, including Wohlford. He rejoined Dayton Boots as operations manager in May 2020, two decades after the family's ownership stake in the company was sold.

The offer to return was extended by Hutchingame, he said, and came with the condition that half his wages would be paid out in gift cards.

"It was weird," said Wohlford, "but I wasn't really looking at the intricacies of the deal. It was exciting to me that after 20 years of being away from my family's company, I was being asked back."

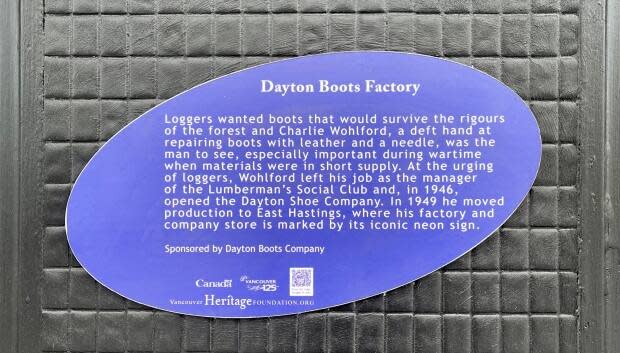

Charlie Wohlford, Ray's grandfather, opened the Dayton Boots factory store in the early 1950s on East Hastings Street where it still stands today.

Dayton logging and work boots were famous for quality and durability. But it was in the late 1960s, when the company started making a style called the Black Beauty, that the brand's popularity exploded.

'No knives. No Guns. No Daytons'

Black Beauties became the embodiment of badass chic, coveted by bikers North America-wide. As urban legend has it, some Vancouver bars even started posting signs reading, "No knives. No guns. No Daytons."

Wohlford still marvels at the fame, and infamy, the boots achieved.

"Anyone over the age of 40 who grew up in B.C. knows Daytons," he said.

Today, the Dayton vibe is more litigious than colourful.

Richard Kobayashi says he is also owed money by the company.

A shoemaker by trade, he joined Dayton Boots in October 2020, agreeing to be paid 50 per cent of his wages in gift cards. Laid off from his previous job when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Kobayashi said he was desperate for work.

'I needed a job'

"Of course, you would think it's kind of strange. But at that time I needed a job. I wanted to get any job within my expertise," he said.

"So when Eric proposed the salary structure where he would pay me 50 per cent in regular salary and 50 per cent in Dayton gift cards, the usual, rational sense was out the window."

Kobayashi exchanged some of the gift cards for boots, and sold some of those online for an estimated 20 cents on the dollar. He quit the company after five months. Looking back, he now feels Hutchingame used the pandemic to take advantage of employees.

"Seeing how these 70 people were affected makes you realize the scope, and how one person could actually affect so many people," he said.

Wohlford worked at Dayton for four months, bailing when he sensed "everything was coming off the rails."

He doesn't expect to see a dime of what he's owed, and says that's OK.

"My father walked those halls … I grew up at that facility," he said.

"I signed up willingly. I felt like I was helping."