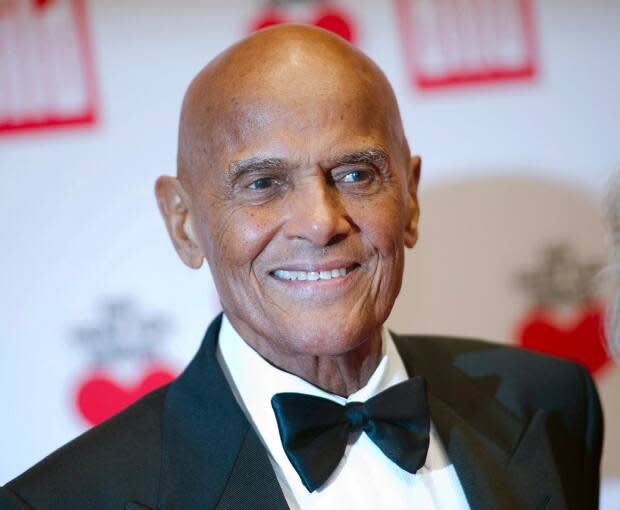

Harry Belafonte, legendary performer and activist, dead at 96

Harry Belafonte, the American singer, actor and social activist known as the King of Calypso, has died. He was 96.

Belafonte died Tuesday of congestive heart failure at his New York home, his wife, Pamela, by his side, said Paula M. Witt of public relations firm Sunshine Sachs Morgan & Lylis.

Belafonte, whose family was Jamaican, spent part of his childhood on the island and popularized Caribbean music with international audiences in the 1950s through hits such as the Banana Boat Song with its iconic "Daaayy-o" callout. He reprised the song for a new generation in an appearance in 1978 on The Muppet Show.

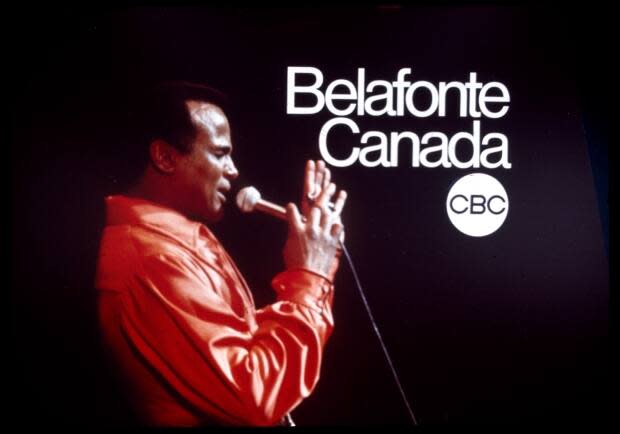

WATCH | Harry Belafonte speaks to CBC in the 1960s on mixing art and politics:

Belafonte had a significant career as an actor, challenging taboos in 1957's Island in the Sun, in which he played a Black man contemplating an affair with Joan Fontaine. The movie was banned in several Southern cities, where theatre owners were threatened by the Ku Klux Klan because of the film's interracial romance.

He won a Tony Award in 1954 for his starring role in John Murray Anderson's Almanac and was the first Black man to win an Emmy in 1959 for his solo TV special Tonight with Belafonte.

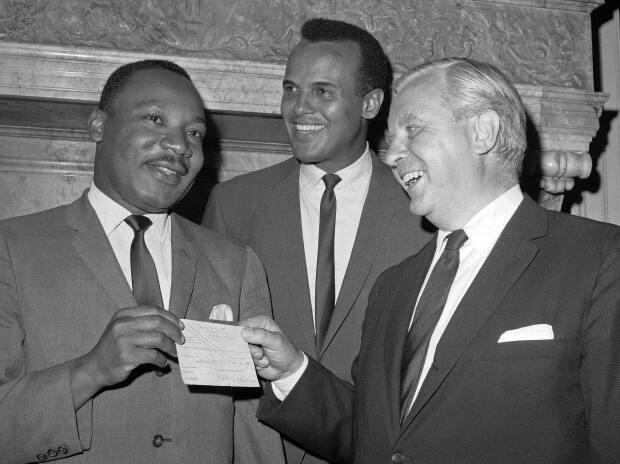

Offstage, he was an active participant in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, often working closely with Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. In 1963, Belafonte was deeply involved with King's March on Washington and two years later helped recruit Tony Bennett, Joan Baez and other singers to perform for the marchers in Selma, Ala.

He also played roles in the anti-apartheid fight in South Africa and helped raise money for food aid with the USA for Africa project and its all-star recording We Are the World, as well as AIDS charities in Africa.

Military service, then stardom

He was born Harold George Belafonte in Harlem, N.Y., on March 1, 1927, the son of a Jamaican housekeeper and a chef who worked in the Royal Navy. He spent part of his childhood in Jamaica, but returned to New York to attend high school.

Belafonte joined the U.S. navy during the Second World War, and when he returned he began acting classes at Erwin Piscator's famed Dramatic Workshop in New York, studying alongside Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier.

He began singing in nightclubs in New York so he could pay for his acting lessons — initially singing pop and jazz, and appearing with the Charlie Parker band in one early appearance.

During this period he developed an interest in folk music and began researching it at the Library of Congress, while also taking an interest in West Indian music. He shot to stardom with the lead role in the musical film Carmen Jones, with music by Oscar Hammerstein.

His first single, Matilda, released in 1953, became a signature song for him and he developed a following by introducing the music of the West Indies to America. His 1956 album Calypso sold over a million copies, a record number at the time.

Handsome and a consummate performer, he went on to record a string of hits including the spiritual Mary's Boy Child and the folk songs Jamaica Farewell and John Henry.

He achieved considerable clout from his commercial success and was able to use it to further the careers of other Black stars, including Miriam Makeba, Odetta and the Chad Mitchell Trio.

Sought to widen Black portrayals

He became TV's first Black producer for Tonight with Harry Belafonte. In a 1969 interview with the CBC, he said he established his own production company so he could bring the kinds of films and TV shows he thought were worth doing to the screen.

"I find no great pleasure in being an administrator, but I found that when I could not do as I wanted to do as an artist with existing institutions, I had to set up the kind of organization that would economically and personally allow me to pursue the kind of things that I was interested in," Belafonte said.

One of the things he said he hoped to do was reshape thinking about the roles of Black people on screen.

"If you want to show us on the screen dancing and smiling … it's fine, but it doesn't provoke any thought, it doesn't rock the boat. It pleases the status quo and leaves everyone out there feeling happy," he said.

On film and on TV he had a series of roles that challenged racial stereotypes. He also played a bank robber with a racist partner in Odds Against Tomorrow, and then starred alongside friend Poitier in 1972's Buck and the Preacher and 1974's Uptown Saturday Night.

In more recent decades, his film roles included Bobby, Kansas City, White Man's Burden and Swing Vote. In Spike Lee's 2018 film BlacKkKlansman, he was fittingly cast as an elder statesman schooling young activists about the country's past.

Following in the footsteps of his hero and mentor Paul Robeson, Belafonte spoke out against both prejudice in the U.S. and colonialism in Africa.

In a 2002 radio interview with NPR, Belafonte spoke of the sense of betrayal he felt, having fought for his country in the Second World War, yet forced to deal with racial discrimination at home.

"Many of us were very, very upset and very angry with the fact that here was democracy, having been fought for so vigorously, not reaching out to those of us who were the victims of the absence of democracy. And in that context, rather than submit, we joined and organized and did everything we could to have the principles of democracy in our constitution upheld," he said.

He was a confidante of Dr. Martin Luther King and provided for his family as King made only $8,000 US a year as a preacher.

"I saw the threats on his life and decided to take out insurance on his life for his family's benefit so that if anything happened to him, they would not be economically destitute," he said in a 2007 interview with the BBC.

Belafonte 'radiates greatness': Dylan

Belafonte befriended King in the spring of 1956 after the young civil rights leader called and asked for a meeting. They spoke for hours, and Belafonte would remember feeling King raised him to the "higher plane of social protest."

Then at the peak of his singing career, Belafonte was soon producing a benefit concert for the bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala., that helped make King a national figure. By the early 1960s, he had decided to make civil rights his priority.

He bailed King and other civil rights protesters out of jail and financed voter registration drives.

Belafonte's admirers included a young Bob Dylan, who played harmonica on Belafonte's Midnight Special and also performed alongside Baez at King's March on Washington.

"Harry was the best balladeer in the land and everybody knew it," Dylan wrote in 2004's Chronicles. "He was a fantastic artist, sang about lovers and slaves — chain gang workers, saints and sinners and children.… Harry was that rare type of character that radiates greatness, and you hope that some of it rubs off on you."

In 1985, he was one of the organizers behind the song We Are the World to raise money for African famine relief, and also performed at the subsequent Live Aid concert.

In 1987, he was appointed as a UNICEF Goodwill ambassador, a role that allowed him to raise the profile of the plight of children in Senegal, Kenya and Rwanda, and the impact of AIDS on the African continent.

Belafonte was sometimes critical of U.S. foreign policy and its long-term effects.

"Our foreign policy has made a wreck of this planet. I'm always in Africa.… And when I go to these places I see American policy written on the walls of oppression everywhere," he said in a 1995 interview.

He was ever engaged and unyielding, criticizing celebrities like Jay Z and Beyonce for what he said was a failure to meet their "social responsibilities."

The country's first Black president, Barack Obama, once asked Belafonte to cut him "some slack" on the performance of his administration.

Belafonte said he responded, "What makes you think that's not what I've been doing?"

Belafonte's life and times were featured in the 2011 HBO documentary Sing Your Song.

In addition to his wife, Belafonte is survived by his children Adrienne Belafonte Biesemeyer, Shari Belafonte, Gina Belafonte and David Belafonte; two step-children, Sarah Frank and Lindsey Frank; and eight grandchildren.