How Jay Versace Got SZA to Talk Her Shit on ‘SOS’

On Thursday, around 9 p.m. Pacific Time, SZA’s highly-anticipated sophomore album SOS appeared on streaming services, exactly five years and six months from the day her deeply beloved debut, CTRL, was released. Jay Versace, who produced two songs on the new album — including the first and titular track, a bold declaration of her extraordinary talent and tested temper — spent the hours before the release walking the streets of Pasadena, where he lives.

“I don’t know why I do that,” Jay Versace says. “But I literally was walking all over, everywhere you could think, just listening to music. Then it dropped, and I listened to the full album and just embraced it.” That evening, he heard the project in its final form for the first time, along with the rest of the world. Afterward, he scrolled through reactions to the album on his phone all night. His name was trending on Twitter, but he preferred to watch people respond to the music on YouTube and on TikTok.

More from Rolling Stone

“I make a lot of what people consider to be boom-bap music,” Jay says. “A lot of the boom-bap community or the hip-hop community, they love to make videos reviewing music.” Knowing he brought a similar style to SZA’s album, he was curious to how hip-hop heads would respond to alternative R&B’s resident It-Girl taking on the sound. SZA starts “SOS,” with searing vocals and a sharp tongue (“Nah lil bitch can’t let you finish, yeah that’s right, I need commissions on mine,” she sings) before rapping — like, really rapping — about who she is and what she’s owed.

“I seen one video,” Jay says. “Somebody was in the club, they was playing it in the club, and they was like, ‘Wait, what?’ They was like, ‘Play that back!’ They stopped the music in the club and played it back! I was just like, ‘Oh my God.’” SOS was almost instantly and universally met with acclaim, and is projected to top the Billboard 200 on Tuesday, earning SZA and her collaborators the first No. 1 album of her career.

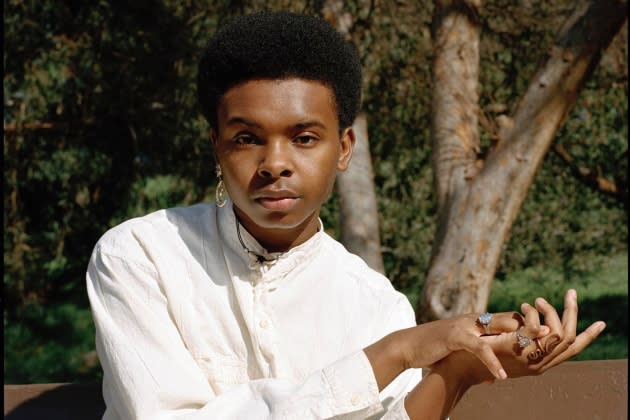

On Saturday afternoon, Jay took spoke to me via Zoom from Malibu, where he said he was staying with a friend. He sat in a spacious, cream-colored room, wearing a white long-sleeved tee and tan beanie. Forty-five minutes into our conversation, as we discussed the SZA songs we loved first (for him, “Caretaker” with DRAM, likely “Hiiijack,” for me), that friend poked her head in the door to get his Starbucks order, her face fuzzy in the distance on the screen.

“Who this?” Jay hollered towards the door. His friend spoke so softly I couldn’t catch her reply. “I’m doing an interview —” Jay said carefully.

“I’m sorry,” she shot back quickly.

“— about you.”

SZA seemed genuinely caught off guard, though Jay had ran my interview request by her and their friends before agreeing. We all burst out in laughter. “Nigga,” she said, her voice louder and deeper. “I feel crazy.” Still, she stayed to confirm that he wanted the iced matcha she suspected he would like.

“I love you,” she cooed to Jay, preparing to pop out but instead engaging in a brief conversation about what seemed like their sleepover the night before.

“Hi, person! Whoever that is,” she said to me brightly. After some cautious fangirling over the album from me, she steered the praise to Jay.

“Thank you. I’m so grateful. Jay deserves all the things. Oh, he’s the coldest,” she said. “I really, literally, I’ve never wanted to rap or make anything aggressive before Jay came into my life.”

“I was like ‘Talk that shit!!!’” Jay reenacted with a wild whisper-scream.

“Nobody has ever gassed me like they have,” she emphasized. “Let me get the fuck out of this interview. I love y’all.”

As SZA’s star was ascending in 2017 with the release of CTRL, Jay was going viral nearly every day with brief and brilliant comedic skits on Vine, a now-defunct predecessor to TikTok. And SZA was using a clip of him making fun of her hit “The Weekend,” in her performances. When Jay found out, they connected through DMs and texts, and maintained a digital relationship for a couple years before meeting in person. By that time, Jay had just begun producing music, under the tutelage of friends like Knxwledge and Pink Siifu. In 2019, SZA invited Jay to a studio for their first IRL link, an awkward encounter that blossomed into a deep friendship.

Since then, Jay has blossomed into a formidable producer, too. His songs — like “Safari,” on Tyler, the Creator’s Grammy-winning Call Me When You Get Lost, “Lil Diamond Boy” by Lil Yachty, and “Versace,” by Westside Gunn, which the Griselda rapper named for the beatsmith he was once skeptical of — are rich, soul-and-gospel sample driven fare that are indebted to the past of Black music as they shape its future.

In spite of his passion, success, and growing list of placements, Jay mostly and intentionally refrained from sharing beats with SZA unprovoked.

“I really value my friendship with people and I know how it can get out here,” said Jay. “I know how people are with me, where I’m like, this person’s so fire. I want to hang out with them. I want to go to movies with them. And then while we’re on the way to the movies, they’re playing me all these beats and they’re doing all this stuff. I understand how that can be really discouraging in the friendship. It can ruin a friendship if you’re using that moment to advance in your career.”

Jay produced the “SOS” instrumental, originally titled “Grief,” over two years ago, without SZA in mind. He made his other contribution, the beat to “Smoking on my Ex Pack,” just a few months ago. It wasn’t until a trip to Hawaii with SZA and more friends in March — mostly a vacation where music happened to get made, according to Jay — that he had heard what she had done with the first beat.

“When she’s excited, she wants to do a surprise,” said Jay. “So we was making beats or whatever and she was like, ‘Come back [to her room]. Then when you come back I’m going to show you something.’” That something was “SOS.”

“I was so shocked because I’m like, ‘This is what I wanted,’” Jay said. “I wanted her to really claim her queen energy that she has because she really had a chokehold on the entire world for five years. How many other people can have people waiting on you for five years and still pow?”

SZA was clear that Jay was integral to the punch of SOS, an album that already feels quintessential. Here, he goes deep into the making of it, the expanse of Black creativity, his skepticism of external validation, and his next moves.

Tell me about Hawaii. What was that like for you?

Hawaii, it was beautiful. That was my first time there ever. It wasn’t like, work, because we’re actually friends. We actually have sleepovers and go to the beach all the time. We don’t publicize it because I’m not really good with showing who my friends is without feeling weird. I don’t want to make anybody feel weird around me. I just like hanging out with my friends. So Hawaii was more like, “Let’s hang out. But also we make fire music, so let’s actually get that together too.” We went to the beach every day because we were literally on a beach. We ate, cooked, and made music.

What city or part of Hawaii were you in? Do you remember?

Don’t remember. I got on that plane, I got in that car, and I just went to wherever we were supposed to be.

Was that when you first got pulled into her album process? Had you been involved in the album at any point before that, or is that really when you became a part of what became SOS?

It was probably a few years ago, where she was just like, “I’m about to do my album. Come to the studio and play me some beats.” That was a few years ago. She was just like, “I need you on my album,” and we were just trying to figure it out, but I was still learning my sound. She was very patient with me as I was trying to figure out mixing and just getting my sound together to really present fire beats for her. She was just like, “I’m doing an album. Play beats whenever.”

Then for the years that followed, were y’all just talking about music every now and then, like playing beats for her over time?

Yeah, it was very casual. We love music, we love riding around playing music, talking about music. So literally it was like, maybe we’ll be driving somewhere and then we’ll be listening to some music and I’ll be like, “Oh wait, that reminds me of this song that I did…” Then she’ll be like, “Oh, save that for me. I think I’m going to write an idea or something.” Or she’ll be at the studio and she’ll be like, “Come by the studio.”

Let’s talk about “SOS” and “Smoking on My Ex Pack,” specifically. Basically, what I’m going to do is ask you pretty much the same questions about both. With those two songs, did anybody collaborate with you? Let’s start with “SOS.”

I’m glad you asked this because some people say, “Oh, did he sample Drake for that song? He sampled “Champagne Poetry?” I played that beat for her when we was in Hawaii, but I actually made that beat three years ago. Wasn’t even making it specifically for anybody. I’m a gospel head, I listen to gospel all day long. I was just chopping gospel samples. I heard that, “Last night” [in “Until I Found The Lord (My Soul Couldn’t Rest)” by The Gabriel Hardeman Delegation] and I was like, “Uh-huh, loop that boy up!” I made that beat literally way before Drake’s album even came out.

I mean, I don’t know how long Drake was working on his music, but there was no crossing of paths? You never heard anybody use that sample before?

No.

Are there any other parts of making that beat that you want to describe?

I have different eras of my producing career. That was when I was really into just hearing something. I like vocal samples. I like when people are saying something in the sample. My first big placement was with Westside Gunn [with “Versace”]. It was a gospel sample and it was like they were saying “Blood of the Lamb.” I was like, This reminds me of my mom. First thing I did when I made that beat is I sent it to my mom. I was like, “This reminds me of something that you would listen to.” That was when I sent it to Gunn and then he used it

You said you wanted her to talk her shit, that’s a thing that you were encouraging her to do. When you heard the lyrics with “SOS,” were you proud? Were you surprised? What were the feelings you remember having?

I believe that spiritually our ancestors, the people around us, they can use us spiritually for whatever we’re trying to convey. I feel like that’s something that she wanted to do. I feel, even though I was telling her to talk her shit, I feel like that was something that she wanted to do too. I feel like she never really got the chance to really do that.

When I heard those lyrics, I was like, This is her ancestors using her to really push whatever she needed to push out. It just released. It felt powerful. I don’t think anybody has heard her voice like that on a song. I was literally really just in awe of the monster that she released when she was rapping and singing on that song.

When did you become aware it was going to be the first song on the album and the title track?

I think it was random. She says stuff so random in conversations. I think it we was eating or something. I don’t remember when, but she was like, “Oh yeah, that’s going to be on my album. That’s the first song on the album.” I was just like, [Jay looks around frantically, mimicking his surprise] “Wait. Okay.” We just kept talking. I didn’t know it was going to be “SOS,” which is the name of the album, until literally this month.

I didn’t even know until she put the track list [on Twitter and Instagram]. “Grief” was the name of the beat, [but] she said I’m going to be the first beat on the album. [Recalling his thought process] This say “SOS,” then that must mean that’s my track. Then I looked at the production and I’m like, That’s my song.

I give people so much space when it comes to their creativity. I don’t ask them too much. I don’t ask, “Oh when is this? What is this?” I’ve never asked her when she’s releasing, what she’s going to name it, [or ] if shes’ going to use it. I don’t ask anybody because I don’t like when people ask me. I just was like, I’m going to let her come out with whatever she’s coming out with.

Do you have a favorite line or favorite lines from “SOS?”

That whole song, when she was saying, “I just want what’s mine.” Anytime people talk about they need their credit and they just want what’s theirs, I’m like, “Yeah.” So many people don’t get the proper credit. There’s barely any Black people that really get the credit for the stuff that they do. I just love hearing that from Black people, especially Black women.

I feel like we’re all just told to just stay humble and if something happens to us, take the easier route or just don’t express how you feel. Just let it go and just appreciate.

So now let’s go through “Smoking on my Ex Pack.” Did you produce that by yourself? Anybody else contribute to it?

I produced Smoking on My Ex Pack and I literally made that for her. That song was inspired by just rap songs that I heard growing up, that I wanted to hear her either singing or rapping on. That was specifically for her.

What does it sample?

Webster Lewis’s “Open Up Your Eyes.” That’s not a gospel song. That’s a little love song.

How did you find it?

I’m really into ballads, seventies Philly ballads and [from] Jersey and New York. They had a really crazy instrumentation in their music that people don’t really look at and that’s where I’ll be looking at. I probably shouldn’t say that because that’s my secret hiding spot to look for music that I sample, but it’s so much stuff there.

I think I just ran across that song and I just let it play. I immediately loved the horns. Then that’s when the lady was like, “You can trust…” and then the way she just went off like “Meeeeeee,” I was like, That’s fire. I was like, Let me put this in into Ableton and I’m going to make a beat for Solána for this because this is fire.

At that time I was listening to a lot of Dipset, Camron, stuff like that. I [wanted] to make a sound, something where someone could be on just some boom-bap, hip hop stuff that reminds me of just driving around with my dad when I was a little kid. I chopped [this] up and then sent it to her.

Did she respond pretty quickly?

I think she texted me and she was, “Your beats are so easy to write to. Why am I already writing lyrics right now?” Then when she sent that song back, I was like, “Yes.” The song was actually originally longer. That song you all hear is the second half of the song. . She was just a little bit….like, “It’s my first time rapping. I don’t know what people are going to think.” Then she just put half of it out, but now people love [it], everybody’s like, “SZA’s a rapper. SZA’s a rapper!” Now she’s just like, “Oh, shit!”

The rapping is so phenomenal. She’s so good at everything. How many beats do you think that you’ve provided SZA in your friendship? It can be a very rough estimate.

[Going into their text messages to count] It’s probably 15 songs that I sent her. But she also sends me stuff too. So it’s like even. When she sends me music, that’s when I send her music.

How did y’all become friends?

So she used to put my videos in her performances. So when she made [“The Weekend”], I just moved from Jersey to LA. When I was in Jersey, everybody was singing that song, “My man Is your man…” It got annoying at some point. So I made a video just making fun of it. I was like, “How girls be when they hear SZA.”

Then she loved the video and she started putting it in her stage performances on the screen while she was singing. And I was like, okay, she knows who I am. I wasn’t even making music. We started talking and being friends, DMing, texting. When I first started making beats, she was one of the first big people to get me in the studio. That’s when I first met her, in the studio [around 2019]. We was both equally nervous and shy. But then we just started playing music and just started having fun and it was fire and then we just kept doing it.

Now that you’re a part of her creative process and a friend of hers, what would you say her music means to you now? And is it different from what it meant to you before you became a part of it?

I feel like it’s way more personal. Everybody [keeps] saying, “how are you?” Even at the release party, and I was like, “I’m just in shock.” I have a personal connection to those songs where I’m just like, wow. It feels like these are my songs. I feel like they’re my babies too.

Just in general I like when people make art… I like the way she… This is why she’s my favorite: I like the way she makes her art because people can perceive it in whichever way they want. When people just have to figure out their own definition of it, that’s when it’s really timeless. Because people can live their entire life creating different definitions and coming back to it. [SZA] makes things like a coloring book. You put your own colors into the lines, but she’s just creating the outline for you. There’s not a lot of people that does that. She doesn’t really explain exactly specifics — what she’s talking about or who she’s talking about. She’s just saying, I feel like people don’t treat me like this…And that’s why she’ll always go crazy. People will always love her music.

It’s so interesting because she accomplishes that, but there’s also… There’s a specificity to it. It’s not who she’s talking about or the situation, but the verbal descriptions are so colorful. You’re able to make interpretations and add yourself to it, but there’s also character and directness. Does that make sense?

Yeah, it definitely makes sense, especially with this album. She’s definitely at least more telling her story more with this, telling exactly what’s going on. But I think even still then, I think that passion that she has… Even with those two songs that we did, the passion that she has is something you can go take on a jog. You can work out and listen to that. It’s motivating, but it’s also like, she’s talking about herself, her own life, her own… So it’s that passion doesn’t go anywhere.

Even if it’s something where she’s completely talking about every little thing that’s happening, she’s still really emotionally outpouring, which is something that a lot of people don’t do nowadays, where we feel like we can’t do.

When you say people feel like they can’t emote in the way that she has on this album, what do you mean? Where do you think that comes from? Where have you observed that?

I think we have a hard time expressing ourselves. I think it’s not easy for us to express ourselves and to be vulnerable, especially publicly, especially as Black people, because it’s dangerous. It’s literally dangerous for us to be vulnerable, be emotional, just to talk about things that are bothering us, to tell someone I’m tired. To tell somebody I’m sad, to even cry. And all these things are targets for us to be attacked or lose our job or something like that.

[SZA] don’t care about the consequences that may come with what she’s saying or how she’s saying [on this album]. She’s just going to say it.

I was listening to some of the music that you’ve produced and people tackle it so differently, Like Boldy James does it differently than Yachty did, who does it differently than Denzel Curry did. Or Tyler, the Creator. When you hear these vocal performers take your music and do their thing on it, what does that do for you?

That’s what I look for. I don’t want people to sound like… Somebody just asked me at a DJ set that I did, “Why don’t I hear you on more albums? Why don’t I hear you in more music?” And I was just like, “Because everybody sounds the same.” And if I wanted to make the same song three million times, then I could easily do that. But I’d rather make stuff that sounds different.

I love that people have their own significant texture or voice. If you don’t have that, I cannot send you any beats because I literally cannot listen to one more song of somebody with the same flow that’s like every single song that I’ve heard for the past three years. I literally look for somebody to come with something new.

So then what else have you been up to this year? You’ve been talking to SZA about her album, you guys went to Hawaii. You’ve made these two wonderful songs. What are the other things you’re proud of that you’ve done this year professionally?

The Grammy, I’m really proud of the Grammy [for Tyler, the Creator’s Call Me If You Get Lost].

Do you get a statue or do you get something else?

It was a picture of a statue. It was a Grammy picture. I was still appreciative, but that was something I was really happy about. Honestly, this year I tried to detach myself from materialism. . I’ve been really trying to work on distracting myself from validation, just making cool stuff, putting it out. I receive the love and I’m appreciative, but I do that temporarily and then I just move on to whatever my mind calls me to do next. I don’t want to sound ungrateful, but that’s literally how I don’t get caught into what everybody else is doing. I don’t really have a lot of things this year, besides the Grammy and [SOS], that I was super emotionally invested in.

I think that you’re our own growth, our own self-actualization is something we can be proud of. Since you’re saying you’ve spent time trying to detach yourself from finding validation and accomplishments, can you talk a little bit about the ways that you feel like you’ve grown personally because of that?

I need to find out who I am and really be happy with it and really just work with that, ’cause a lot of times the advice I give everyone when they ask me for advice, is like, “How much of yourself is involved in your creative process and your life and stuff like that?” I always tell people, and applause is not always a good thing. When people are applauding, that’s not always a compliment. Sometimes that’s holding you back because sometimes you’re not even supposed to be doing [the thing you’re being applauded for].

A normal person would do that thing for the rest of their life ’cause they have everybody clapping for them. But my thing is, that’s validation. We’re doing that for validation. So how much of what you’re doing is not involved with what somebody applauded you to do? So, that’s my entire year of just figuring out, “Do I actually like this or am I just doing this because people saying, ‘Congratulations, keep going?'” That’s literally my entire motivation right now.

That’s really powerful. Finding internal motivation as opposed to external motivation can be really hard, especially if your career is public, because you have to put the work out and art is meant to be discussed. Writing is meant to be discussed. It’s meant to be thought about. It’s supposed to make us better as individuals and as a society. So, you could make your things and just keep them, but that’s not necessarily the function of the work. So divesting from the praise, the applause, the validation, that really resonates with me.

I’m just being really transparent. Making those [comedic] videos was miserable for me. I was really going through a lot at that time. But people were telling me, keep going, keep going, keep going. I was like, “Am I living my dream right now?” It was a lot. That’s when I really noticed that. I was like, “I think I‘m living my dream. I don’t know, ’cause people keep telling me to do this, but I hate it.”

There had to come a moment where I literally looked in the mirror one time and I was seeing myself as a little kid and I was like, “He don’t like this.” I just really had to look at myself outside of the fame, the followers, all that. I’m like, “What does he want?” I was like, “He does not want to do this,” and I literally stopped. That’s literally when I started making music. I ended up into a Grammy and now I feel like I’m fully making him happy, making that little child and me proud because I stopped listening to, “Oh, congratulations!”

What fuels your creativity? When you were making those funny videos on the internet, it was still very creative. What fueled that creativity, and then what fuels your creativity now? What’s the same, and what’s different?

I’m still the same funny person, but I just learned how to use my weapons when they’re needed. Instead of making a whole bunch of people who don’t care about me and who laughing at me instead of being a clown for them, I’d rather go and hang out with my friend when they’re sad and just cheer them up. That’s how I’ll use that [humor], or if I’m sad and I’m going through something, I’ll just make music or create. I’ll use my musical talent to help me through that.

I know that I’m a multi-talented person. So now I’m using it in a way that benefits me and doesn’t hurt me, because some of your talents can hurt you sometimes, especially if that’s not supposed to be your destination.

All I do is joke around. ? I can’t have a serious moment for too long. I’m just not built that I grew up around uncles and aunts, somebody going to say something that’s funny. I’m the person that walks into the repass and tells funny jokes. I’m the same exact person, but I’m not a clown. There was a time where I was literally depressed and people were like, “Oh, you’re that funny guy.” I’m like, “My life is not funny right now.”

We’re wrapping up, I only have a few more questions. You did an interview with Charles Holmes for Rolling Stone in 2020. I guess we’ve talked about so much, but if you had to reflect on the time since your first Rolling Stone feature, what would you say?

A lot has changed. I’ve learned different things about sound now. I would say the biggest thing that has changed is I’ve realized that texture…There was this point in time where I was just like, “I love music from the ’90s, the ’70s, the ’80s, and I want to recreate that.” I would say the biggest thing that has changed within me since then is that I realized that it’s not the time period that we miss, it’s the texture that we miss.

When you look at the early 2000s and how people like to dress, like Aaliyah and certain people, people want to recreate those outfits [now], but sometimes it is not the outfit, sometimes it’s the fabric. That’s what I’ve been incorporating my music, not trying to make something specifically of a genre of a time period, more like [asking], “What hardware was they using? What software did they use? What type of drums did they use?” And actually using that and making stuff that I think is futuristic, but using tools from the past. Hopefully, with the next thing that I release, people can hear more of that.

Are you open to sharing any details about what you’re working on?

Yeah, I’m working on my album right now. I just started putting some songs together and I really want to make something that’s not just beats on a playlist. I want this to actually sound like an album. Hopefully that it can be released next year.

Are you thinking of a more instrumental project, like Kenny Beats put out this year? Are you thinking having different vocalists perform on it, whether they’re rappers or singers?

I want to do both. I want to have beats on there, so just instrumentals, but then I also want to have people pop in and out — maybe somebody sings, maybe somebody raps, maybe somebody plays the drums. I want to just incorporate anything that I think is fire and just have somebody come do it. I don’t want to make it a clout thing like, “Oh, he’s just bringing all these famous people on this album.” I want it to be like, “No, it’s these fire ass songs.” So that’s why I’m really putting a lot of intention into it, just trying to make it as fulfilling as an actual album.

I think I understand. You want it to sound cohesive and have ideas that string it together, even though some of it might be instrumental and some of it might be vocal and some of it might be one person and some of it might be someone else. You still want it to feel whole.

I want it to feel like it’s a whole, full album that people can play through and not just press a song because they [see] some somebody on it. I don’t feel like I’ve really heard an instrumental album when it didn’t just sound like people just rapping on beats, which I can’t really explain it. I just want to be the first person to do it, though.

Best of Rolling Stone