Judicial activism has had vastly different impacts in Brazil and the United States

Earlier this summer, Brazil’s top electoral court banned former president Jair Bolsonaro from running for office for eight years. Bolsonaro is 68 and will be unable to run for president until he’s 75.

Five of seven electoral court judges supported the ban on Bolsonaro, who, in the lead-up to the 2022 election, spread misinformation about the legitimacy of Brazil’s electronic voting system.

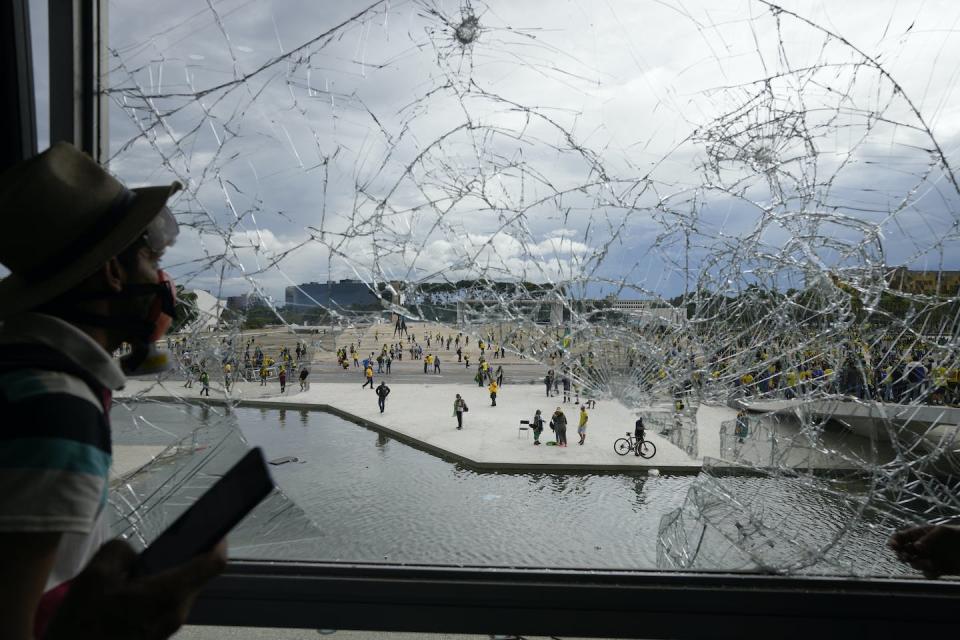

Brazil’s election was marred in violence, with voter suppression tactics occurring before the election. After the vote, thousands of Bolsonaro supporters stormed the Presidential Palace, congress and the Supreme Court.

“This response will confirm our faith in the democracy,” said Alexandre de Moraes, a Supreme Court justice and head of the electoral court, as he cast his vote against Bolsonaro.

The former president is expected to appeal the ruling. However, he still faces 15 cases in the electoral court along with several ongoing criminal investigations. They encompass accusations that he improperly used public funds to influence the electoral vote and target his role in provoking his followers to violence on Jan. 8, 2023.

A conviction in these cases may render him ineligible to ever run for office.

Lessons for the United States

The court’s ruling demonstrates an essential milestone in Brazil’s young democracy while offering lessons for other countries. That’s particularly true for the United States, where former president Donald Trump is the frontrunner to be the Republican presidential candidate in 2024 despite being under two indictments.

First, it indicates that Brazil’s institutions tend to respond vigorously when they perceive threats to democracy and prioritize preserving institutional stability.

Second, it highlights the proactive engagement of legal systems in addressing substantial modern risks to democracy, like disinformation, hate speech and attempts to manipulate voters.

Finally, it establishes a precedent to punish leaders, even presidents, who try to manipulate voters and stoke polarization.

But there are also important implications about the role of the courts in elections and the impact of judicial activism.

Bolsonaro — evidently inspired by his close ally, Trump — followed a similar trajectory after losing his re-election campaign. Like Trump, he resorted to casting doubt and spreading misinformation about his country’s electoral system, ultimately leading to the storming of their respective democratic institutions.

But the aftermath of their actions has unfolded in very different ways.

In Brazil, elections are governed by a federal court, which can determine whether candidates can seek office. The courts reacted swiftly after the Brazilian election, barring Bolsonaro from re-election, citing a threat to the country’s democracy.

American elections, however, are run by individual states, with different policies determining eligibility. Trump’s fate is therefore left up to the voters and the deliberative U.S. judicial system.

Judicial activism

The striking difference between the two cases is the role of the judiciary in federal elections. In Brazil, the court took on a role as a political regulator, fuelling a debate about judicial activism.

Judicial activism — when the judiciary takes an active role in addressing instability, threats or inequality rather than simply responding to cases brought by third parties — is attracting growing interest from scholars.

The active role of courts often comes into play when democratic institutions are under threat, slow to act or neglectful in making crucial decisions or passing significant laws, leading to potential instability or dangerous legal loopholes.

Judicial activism has been particularly evident in the case of Bolsonaro. A culmination of electoral misinformation, violence, threats against the judiciary and political instability resulted in the electoral court’s intervention.

This strong judicial response resulted in the loss of Bolsonaro’s political rights. It raises an important question: how far can a judiciary, intended to be independent and impartial, involve itself in the outcome of democratic proceedings?

Some scholars point out that judicial activism can have negative effects on society.

This is especially true when a president appoints court justices based on their political alignment and agenda. Trump did so and the result has been the endorsement of anti-abortion laws by the U.S. Supreme Court. Another example is in Venezuela, where the judiciary has supported President Nicolás Maduro, resulting in the persecution of politicians who oppose his established regime.

The role of the courts in determining Bolsonaro’s fate has fuelled far-right extremism in Brazil. The Supreme Court has become a target, with threats and violence directed at its judges and their families. De Moraes and his son, in fact, were recently attacked at an airport in Italy by three Brazilians.

Overreach?

Bolsonaro’s followers believe the judiciary has overstepped its bounds, intruding into the political arena. This sentiment could benefit politicians endorsed by Bolsonaro in upcoming elections.

On the other hand, right-wing politicians who employ disinformation and hate speech as tools for electoral manipulation may need to change tactics, prompted by the fear of judicial repercussions for voter incitement.

The actual impacts of the electoral court’s ruling, and the future of the far right in Brazil, will be tested during municipal elections in October 2024.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. The Conversation is trustworthy news from experts, from an independent nonprofit. Try our free newsletters.

It was written by: Gerson Scheidweiler, York University, Canada and Tyler Valiquette, UCL.

Read more:

What the US can learn from affirmative action at universities in Brazil

Why Brazil’s Bolsonaro is following Trump’s pre-election playbook

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.