New Kansas political party wants to change how you vote. Can they get around the ban?

Reality Check is a Star series holding those with power to account and shining a light on their decisions. Have a suggestion for a future story? Email our journalists at RealityCheck@kcstar.com.

Imagine walking into the voting booth and looking at the ballot. One candidate’s name is listed twice in the race for state representative – once as a Republican or Democrat and once as a third-party candidate.

Kansas law prohibits this scenario, but it’s exactly what United Kansas, a new political party, wants to achieve.

If the party succeeds, it could upend Kansas elections, challenging decades of Republican dominance in state legislative elections and undermining the power of conservatives to send their candidates to Topeka over the opposition of moderates and Democrats.

It’s a big if.

United Kansas, recognized last month by the Kansas Secretary of State’s Office, has nominated five candidates for the 2024 general election – two candidates for state representative, one for state senator and two for Leavenworth County Commission. All three state legislative candidates are also running in a major party primary, two as a Democrat and one as a Republican.

Under United Kansas’ plan, those candidates would appear on the November ballot twice if they win their major party primary in August. On one line, they would be listed as a Republican or Democrat and on a second line as a United Kansas candidate.

Voters could still only vote one time. The votes the candidates receive from both ballot lines would be combined for their total. Like every other election, whichever candidate has the most votes wins.

But Kansas law prohibits any person’s name from appearing more than once on a general election ballot, with small exceptions for special elections and races for party precinct positions.

United Kansas’ leaders are readying themselves for a legal confrontation over the ban – their supporters will argue the restrictions violate voters’ constitutional rights – even as the party signals it’s uncertain how state officials will react.

“We need to be prepared for that and we are prepared,” Jack Curtis, the United Kansas chair, said.

The idea at the core of United Kansas, called fusion voting, has a long history in the United States. Sometimes called cross nomination or multi-party nomination, it was once a common part of politics, especially prior to the 20th century. Today it is widely practiced in New York but few other areas.

Before the Republican and Democratic parties achieved the near-total dominance they enjoy today, smaller parties would often team up to jointly nominate a single candidate or give their ballot line to a major party candidate. Fusion voting allowed smaller parties – and the voters they represented – to still influence election outcomes even when they were unlikely to win elections outright.

Most states have since banned or heavily restricted fusion voting, part of a backlash to progressive and populist-era politics. The Republican-controlled Kansas Legislature passed an anti-fusion law in 1901, part of its fight against Populist and fusionist candidates in the years following the 1893 legislative “war” when Populists took armed control of the Kansas House.

Modern fusion voting supporters say it exerts a moderating effect on elections. Voters who have a difficult time casting their ballot for a Democrat or Republican candidate may be more likely to vote for that person under a third-party ballot line. And candidates elected with the help of fusion votes know they must pay attention to the concerns of fusion voters to continue enjoying their support.

At a time of sharp polarization, fusion voting offers a way for voters to push back against candidates on the ideological fringes, supporters say. United Kansas says it wants to break the two-party “doom loop” and encourage political coalitions and compromise.

“It doesn’t take a degree in political science to know that there is a mess and it is not working as effectively as it should be. There’s always a better way,” said Curtis, who leads the new party along with Sally Cauble, a former Republican member of the Kansas State Board of Education, and Aaron Estabrook, a former Manhattan city commissioner.

‘Test the waters’

Kansas law poses major obstacles. Modern state statutes contain several provisions that prevent fusion voting, including a requirement that no candidate may accept more than one party nomination.

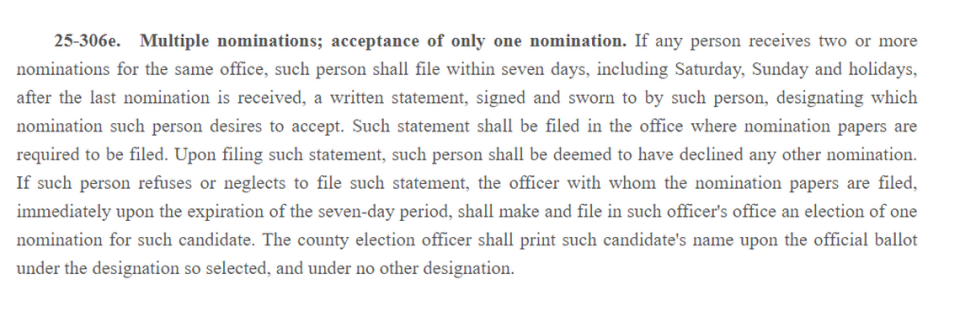

Asked how Kansas Secretary of State Scott Schwab will handle the United Kansas nominations, spokesperson Whitney Tempel pointed to KSA 25-306e – the state law that limits candidates to one party nomination. If candidates are nominated by multiple parties, they have one week to decide which one to accept; if they don’t choose, Schwab chooses for them.

At this point, none of United Kansas’ candidates have technically been nominated twice. They include Rep. Jason Probst, a Hutchinson Democrat; Lori Blake, an Assaria Democrat; and J.C. Moore, a Republican challenging Republican Sen. Chase Blasi of Wichita.

Probst and Blake have no Democratic opponents, and barring an unforeseen event appear set to test the Kansas ban on fusion candidates after they formally win their party primaries in August.

Blake said the potential legal issues surrounding the United Kansas effort were a concern but that she ultimately agreed to be nominated by United Kansas.

“I think sometimes in order to make change, we have to test the waters. If that’s where it goes, I will be a part of that,” Blake said of a legal challenge.

Probst said he agreed to allow United Kansas to nominate him after speaking with individuals from the party several months ago.

“There’s a lot of people, particularly west of me, who would be really good in government, who would be good representatives and could do some good things. They cannot get through a Republican primary. Same thing can be said in some Democratic areas,” Probst said.

By way of example, Probst mentioned Steve Morris, a moderate Hugton Republican who was the Kansas Senate president from 2005 to early 2013. Morris was defeated in the 2012 Republican primary by a conservative challenger, part of a larger effort by then-Gov. Sam Brownback and other conservatives that year to oust moderates.

“I think our primary system is really widening the divide and I think we could create an alternative in some areas where that’s the case – where there’s nothing to choose from but a Republican primary or a Democratic primary – and we can provide another option for people who might be a better option for the community and the state, I’m willing to support that,” Probst said.

Legal challenge likely

Whoever sues to challenge Kansas law – whether United Kansas, a candidate or a voter – will likely argue the restrictions violate rights to free speech and association. A third party is fighting an anti-fusion law in New Jersey on similar grounds.

The Kansas Constitution says “all political power is inherent in the people,” that “all persons may freely speak” and that the people have a “right to assemble” peaceably.

Beau Tremitiere, counsel at Protect Democracy, a group that aims to defend American democracy against authoritarianism, said modern litigation surrounding fusion voting has often centered on the right to association. Protect Democracy, which supports fusion voting, has been in communication with proponents of fusion voting in Kansas.

“It really just gets to the heart of can a group of people work together in pursuit of their goals – can they name the person who best represents their interests?” Tremitiere said. “Few things are as central to that right as being able to name who your standard-bearer is.”

A successful challenge to Kansas’ anti-fusion laws would likely require convincing the state Supreme Court – not a federal court – to overturn the ban. The U.S. Supreme in 1997 affirmed the power of states to restrict fusion voting, upholding a Minnesota law that prevents candidates from appearing on more than one party’s ballot. In the 6-3 decision, the high court found the state law didn’t violate federal rights to association.

The Kansas Supreme Court has shown a willingness to interpret the state constitution to provide additional or stronger rights than those guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. In 2019, the court ruled that the state constitution protects bodily autonomy, securing the right to abortion at the state level just three years before the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Still, the Kansas Supreme Court last month ruled that voting is not a fundamental right.

Of course, the GOP-controlled Legislature could repeal the state’s anti-fusion laws, but there’s no indication that’s imminent. Kansas Republican Party chair Mike Brown didn’t respond to a request for comment about United Kansas.

Kansas Democratic Party chair Jeanna Repass said the party puts its full support, faith and effort behind Democratic candidates. The party is heavily focused this year on ending Republican supermajority control in the Legislature, which would prevent Republicans from unilaterally overriding vetoes from Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly during her final two years in office.

“We don’t have a comment about any other parties,” Repass said, adding that “our goal is to elect as many declared Democrats as possible.”

Moore, the United Kansas candidate who’s challenging a sitting state senator in the GOP primary, said he agrees with the new party’s aim of bringing the state toward the middle. Moore, who calls himself a moderate Republican, previously served one term in the Kansas House, in 2019 and 2020.

“I think most Kansans are very moderate in their views,” Moore said, “And the Legislature advances to the tune of the money, basically.”