Kansas WWII vet who survived 171 consecutive days of combat to be honored in Normandy | Opinion

A single day in combat, 98-year-old World War II veteran Bill Casassa, of Shawnee, told me, “is forever. It goes on and on and on.”

There is confusion, mud -- “always mud” -- and behind the battles, the “brutally hard work of just fetching the ammunition or the gasoline.” There’s the “physical agony of being half-frozen” half the time, and always, during direct engagement, “you know any second now, more rounds can come screeching in. Somebody always got hit and they were screaming. My main memory of combat is terror.” Not mere fear, “but terror.”

I asked Casassa whether he felt, as the D-Day paratroopers depicted in the 2001 miniseries “Band of Brothers” told historian Stephen Ambrose, that they had to consider themselves dead already to really be able to fight. Yes, he said: “When it’s really bad, you’re dead already, so you’ve got nothing to lose.” But “getting dead” mentally was not a one-time ordeal. Because once you’ve come through the day, hope comes creeping back in. So that the next morning, if you are lucky enough to be “alive again, you know you’re going to have to go through the same section of hell to get dead again. To get dead again, you’ve got to go through some awful stuff.”

For an astonishing 171 consecutive days, that’s what Casassa did.

Donnie Edwards, former Chief, helps send veterans to France

The first of those days was November 18, 1944. That’s when, as part of the 638th Tank Destroyer Battalion in support of the 84th Infantry Division’s initial attack on the Siegfried Line at Geilenkirchen, 19-year-old Casassa, of Fitchburg, Massachusetts, rolled into this lovely village — Apweiler, he thinks it was — in his M18 Hellcat tank destroyer.

He saw bricks flying into the air, and an American on a radio running a fight and hitting the dirt periodically, because he could tell from the sound of the rounds when to duck. Finally, Casassa called to an American he saw dodging from doorway to doorway. “Hey Mac, where’s the front line?” The answer, of course, was this: “You’re on it.” He went on to fight in the Rhineland Campaign, in the Ardennes, and in the Central Europe Campaign in the spring of 1945.

Just as he was telling me about getting frostbite in both hands and feet in Belgium, despite knowing the New Englander’s trick of rubbing your skin with snow, the phone rang. It was former Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Donnie Edwards and his wife Kathryn Edwards, whose organization, the Best Defense Foundation, will be bringing Casassa and about 50 other World War II veterans to Normandy for the 80th anniversary of D-Day. They had news: Casassa will be among those receiving the French Legion of Honor Medal — France’s highest honor, civil or military — on June 6.

“You must forgive me; I’m more or less speechless,” Casassa told them. “I’ll be doing this for the outfit — all the guys — but still and all, wow.”

French President Emmanuel Macron will present him with the medal, and President Joe Biden, King Charles and some 25 other heads of state will be there to thank Casassa and the others for — sorry, Bill — saving democracy.

I say “sorry,” because Sgt. Casassa has impressed on me that he does not want to see himself made out to be heroic in this column, and does want me to clarify that he was not in Normandy on D-Day, but arrived in Cherbourg, France, three months later, on Sept. 15.

I also should, according to him, say that all he did was “show up.” And I must make plain that he in his tank destroyer did not personally liberate any death camps, though his outfit did, twice, and he will never forget the smell of what he initially thought must be an abandoned slaughterhouse at Ahlem. As he rolled past, and others went in, on April 10, 1945, “the wind changed and a stench — the foulest, vilest, most terrible smell” — overwhelmed him. “Looking back, it was the smell of pure evil.”

Concerned about rise of US antisemitism

The death camps he did not liberate have stayed with him all these years, though, and he’s still angry that American soldiers weren’t told what was behind that smell, which he thinks would have made them fight even harder.

“The State Department knew about it, the president knew. Everyone in power knew, so why in the hell couldn’t we have focused our attacks” on the camps? “We could have done more. Two or three days’ difference would have saved thousands of lives.”

Which is one reason he takes the recent rise in antisemitism, particularly on college campuses, so personally. “To have done all that and then to have this happen in our own country is kind of a slap in the face.”

After the war in Europe was over, Casassa was sent home to rest up and then train for duty in Japan, so he was still sure he would die before his life had really even started.

Then, when Truman dropped the atomic bomb and the war ended, “I was going to live! I was going to live! I was going to live! I had survived. … I never expected to.”

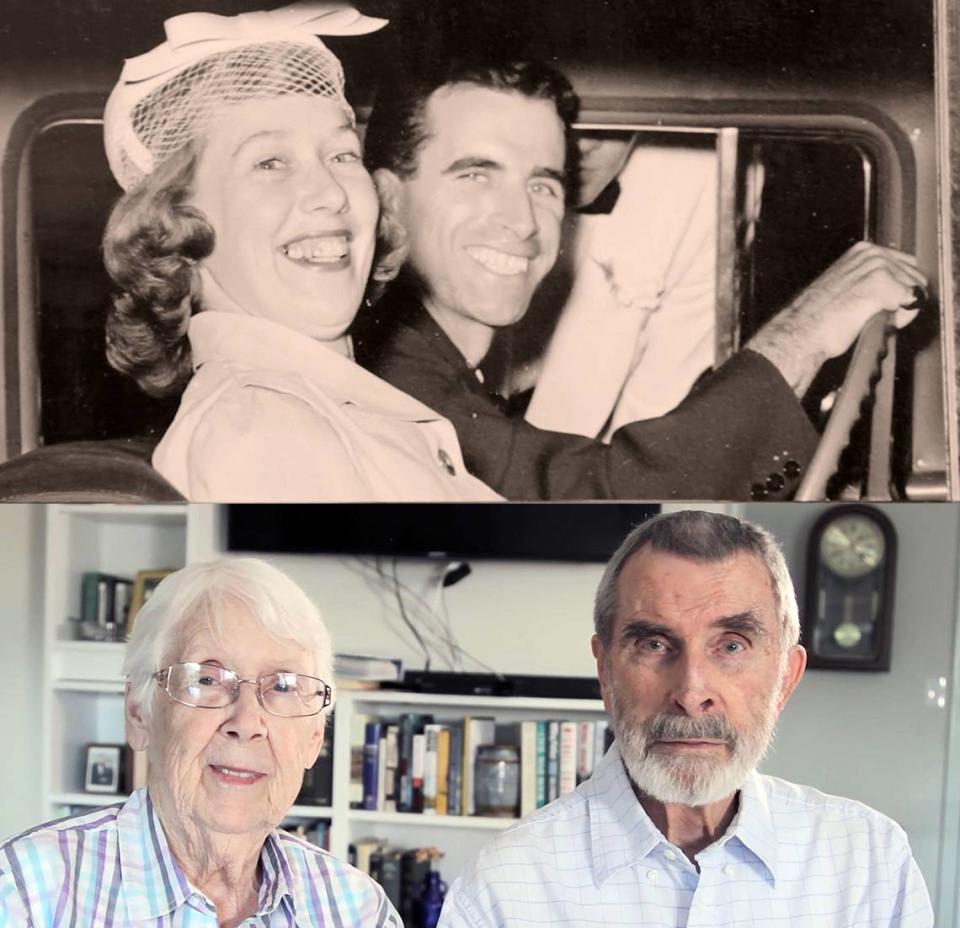

Through his work as a salesman for a candy company in Boston, he met a girl — Maggie, a D.C. native to whom he will have been married 69 years on June 25. He was transferred to her hometown, where their son and three daughters were born, and then, in 1966, to Kansas City, a move he calls “the best thing that ever happened to me.”

What’s always fascinated me about D-Day is the improbability of it all, and the fact that a day on which so much went horribly wrong led, less than a year later, to a victory so complete that even the expected guerrilla campaign of Nazi dead-enders never happened.

At the Battle of the Bulge, American troops didn’t even have winter clothes, yet here we are, 80 years later, free but also frustratingly oblivious to those whose willingness to be “dead again,” day after day, saved the world from the Nazis and kept our republic alive.

Unlike too many of us, the French of Normandy have not forgotten the 2,500 Americans who never made it home from D-Day, or the grit and grace of those like Bill Casassa, who insists that he’s “just one of the ones who survived.”