Kimbell exhibition ‘Divinity in Maya Art’ is reminder of culture’s enduring influence

The works in the Kimbell Art Museum’s exhibition on Maya art are well over 1,000 years old, but the curators can’t help but refer to some in modern terms.

Take the “Eccentric” flint scepter depicting a canoe with passengers. The piece looks like “when a roller coaster at Six Flags goes on a deep dive,” said Jennifer Casler Price, the Kimbell’s curator of Asian, African and ancient American art.

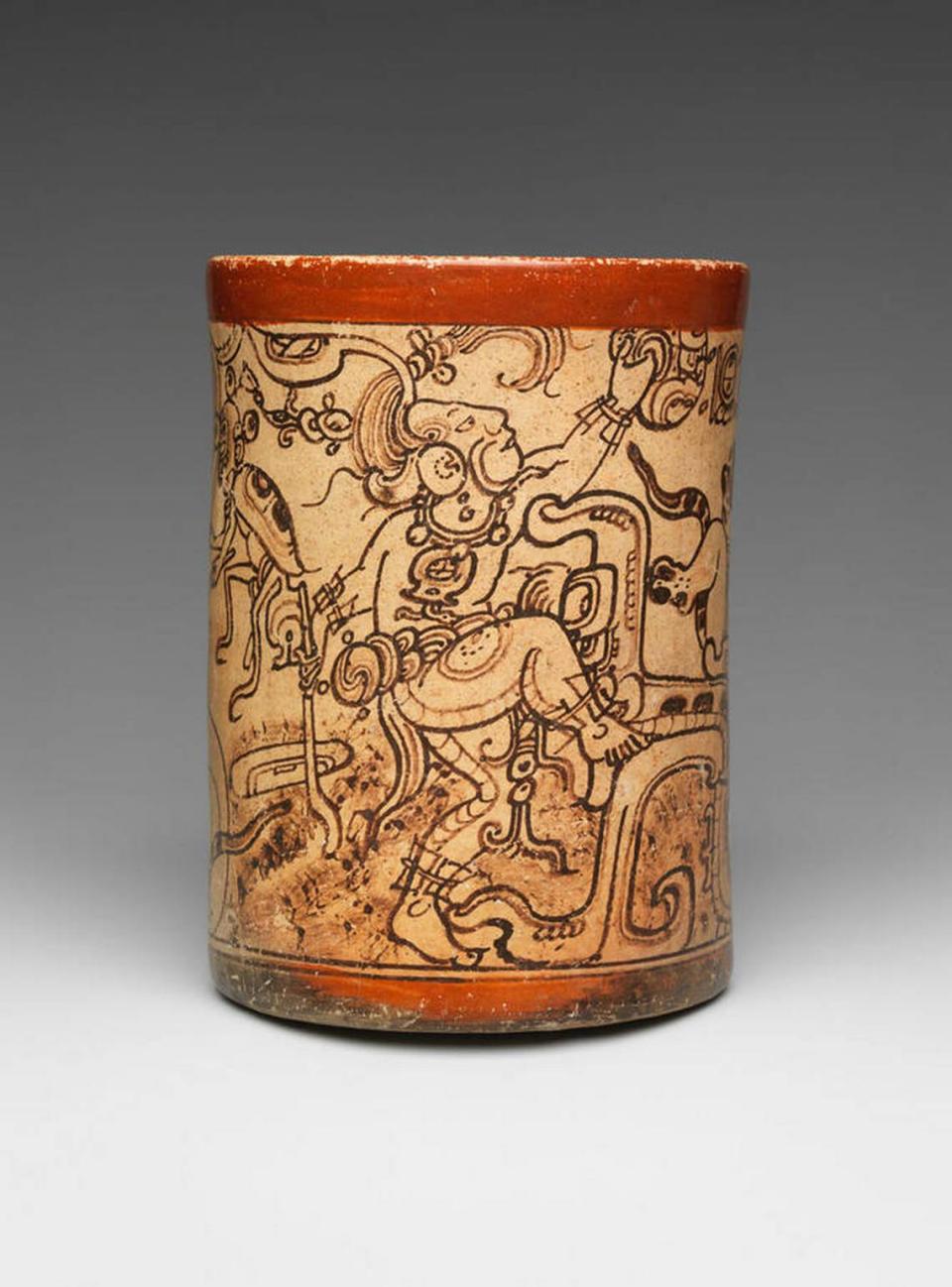

Serving vessels, such as the ceramic Lidded Vessel with Howler Monkey from the 4th century, are the Classical Period royalty’s equivalent of high-quality Pyrex dishware, said James Doyle, a professor at Pennsylvania State University who was previously at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And drinking vessels, decorated with comic-like stories about the deities, were the fine China of the era.

The exhibition “Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art,” which opened in May and runs through Sept. 3, displays nearly 100 rarely seen pieces from 250 to 900 AD that show the early culture’s influence into modern times. The works, including recent discoveries, are from the Kimbell, the Met and museums in Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras.

The show is the first comprehensive look at the relationship between Maya artists, royalty and the ethereal since the Kimbell’s 2010 show “Fiery Pool: The Maya and the Mythic Sea.” A 13-year gap between exhibitions may seem long in the museum world, where a blockbuster Egyptian show tours for five years and Salvador Dali or Andy Warhol display every six months. But the timing is just right, Price said.

For Mesoamerica specialists, each show is a chance for critics and scholars to highlight their discoveries. There are many in “Lives of the Gods.” For Price, the biggest feat is that for the first time, artists are identified. Four of the 20 painters and 120 sculptors who were identified in recent years are named, and three are attributed.

Given artist signatures weren’t even a trend in Europe until the 1800s, “for the Maya to do this in the 7th and 8th centuries is huge,” Price said.

Even as discoveries are ongoing, organizing these shows is getting harder.

There are two factors. One is logistical, with high insurance costs and difficulty in finding reliable transport. But it’s also cultural, as Western museums reckon with the provenance of works that had been stolen or seized. New restrictions by foreign governments and grassroots indigenous groups limit or even ban loans.

Two of the final pieces in the Kimbell show are controversial. The works, Throne 1 and Panel 3, are owned by Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología in Guatemala City.

Doyle called them “next level” and perhaps the exhibit’s biggest gets. Doyle pointed out details in the 19-inch Panel 3 that show rulers paying tribute to an elder on the throne of creation. Throne 1, depicting a similar similar story, was recently restored by the Met before going on display. It was last touched by conservators in the 1930s.

In January, indigenous groups published an open letter to the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture and Sports decrying the decision to loan the items for the exhibit. While Guatemalan law forbids loaning historical objects, a rare agreement between the Met and the Ministry allowed for the transfer of both from 2021 throughout the exhibition. The agreement would allow the Met to restore and display Throne 1 before returning it. Opponents objected because they were not consulted, and the works are not owned by the government.

Drew Eubank, marketing and communications manager at the Kimbell, said they know about the letter but have not received correspondence from Guatemala about the loans.

“It has been an honor to work with Guatemala to bring these extraordinary loans to the Met and the Kimbell in order to study, conserve and celebrate Guatemala’s rich cultural heritage in this groundbreaking exhibition,” he wrote in a statement.

Visitors are reminded Maya culture still exists in the final gallery, where a video by Ricky López Bruni shows a ritualistic dance in Santa Cruz Verapaz, Guatemala. The Maya aren’t an extinct people whose culture died off centuries ago, leaving behind only beautiful artifacts.

In addition to Doyle and Price, the exhibition is curated by Met’s Joanne Pillsbury, Laura Filloy Nadal and Yale’s Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos.