How the loss of Grand Bank's Mabel Dorothy echoed across decades through the crew's descendants

The years of the Second World War, with German U-boats prowling the North Atlantic, were exceptionally dangerous for Newfoundland mariners manning the small wooden schooners carrying salt fish to Caribbean and European markets.

Captain John Ralph and his six-man crew of Grand Bank, in the 167-gross-ton schooner Helen Forsey, had two encounters with enemy submarines within a six-month period of 1942.

It was 80 years ago — at daybreak on April 1, 1942 — on a return trip from the Caribbean, about 1,600 kilometres south of Newfoundland, that Ralph spotted wreckage and lifeboats of a recently torpedoed British merchant ship, the S.S. Loch Don. While being observed through a U-boat periscope, the captain altered course, stopped his ship and rescued 44 of the 47 crew members.

The crew of the Helen Forsey fed and cared for the ship's enlarged company of fifty for seven days, while dodging and avoiding other enemy submarines, before they arrived at Burin.

On his second trip coming back from the Caribbean that year, with a load of molasses, Ralph was not so lucky. German submarine No. 514 was lying in wait 1,900 kilometres east of Bermuda. It was just at daybreak when, without warning, they were fired on repeatedly. The first shell struck the schooner, quickly followed by another. Two of the crewmen —Leslie Rogers of Grand Bank and Arthur Bond of Frenchman's Cove — were killed and Ralph was seriously injured.

Thomas Bolt, Jacob Penwell and William Keating managed to drag their injured captain into a lifeboat with them. Calling upon his master mariner's navigational skills, Ralph set a course for Bermuda. With his other three crew members rowing, they finally landed safely in Hamilton Harbour, after surviving 13 days and nights in their small open lifeboat.

Fast-forward to the mid-1950s and Ralph is now master of the Grand Bank schooner Mabel Dorothy. The days of the salt fishery have come to an end and the remaining schooners still working are involved in the coastal trade, carrying freight including coal, flour and feed between Sydney and various Newfoundland ports.

It was on Nov. 3, 1955, when the 95-ton vessel left Roddickton on the Northern Peninsula bound for North Sydney, N.S., for a load of coal. Weather conditions in the area included wind and occasional snow flurries. This was to be the former bank fishing schooner's last trip for the year and upon her return to Grand Bank she would be tied up for the winter.

We will never be sure what happened on that fateful night to result in the Mabel Dorothy being smashed to pieces and the loss of her seven-man crew: Ralph, mate Herbert Hollett of Grand Beach, chief engineer Willoughby Riggs of Stone's Cove, second engineer Garfield Lawrence of Bay L'Argent, cook Thomas Bolt of Grand Bank, seaman Henry House of Bay L'Argent and seaman Thomas Jensen of Harbour Breton.

It was common for many seamen to keep their families informed of their whereabouts by wiring a telegram home whenever they arrived in a port. Nov. 8 was the birthday of Ralph's wife, Sylvia, but a telegram didn't arrive that day or the next. The families of the other crew members also began to get concerned that something terrible had happened. After a couple of days Manuel Bolt, son of the schooner's cook, went to see the owners, Forward and Tibbo Ltd., to find out if they had any information about the ship. They didn't.

After several more days passed, the Royal Canadian Air Force, with the help of ships in the area as well as the U.S. air force, began searching. The families' worst fears were realized on Nov. 14 when wreckage was sighted. The next day parts of the doomed schooner were found scattered over a wide area, including the Horse Islands near the entrance to White Bay, Hooping Harbour, Jackson's Arm and Twillingate. A smashed dory was found and there was some hope that the crew might have escaped in the other dory — but it was not to be. Then the Mabel Dorothy's stern section was found, with part of its nameplate still intact.

At Grand Bank, the vessel's home port, hopes faded and public functions were cancelled as residents mourned their fellow townsmen. After several more days the search for the men was called off. No trace of any of the crew members was ever found.

All the debris from the schooner seemed to indicate she met whatever fate befell her not long after leaving Roddickton. The initial conclusion reached was that she had crashed into the cliffs of the Horse Islands due to stormy seas combined with strong tides that drove her off course.

Another theory

It wasn't too long before another possible explanation surfaced, that she had been cut down by a paper carrier that entered the port of Botwood on the same night the Mabel Dorothy left Roddickton. The doomed schooner would have been steaming on a course that could have placed her directly in the path of the approaching larger Norwegian ship.

On Nov. 15 — the 16th birthday of Ralph's daughter Mae — the search was coming to an end. The blinds in her house, as in all the other homes of the missing sailors, would be drawn shut. But through tears her mother said, "We can't lower the blinds today. It's Mae's birthday."

Mae had a very close bond with her father and was heartbroken to have lost him so tragically and at such a young age. She saw her dreams of becoming a nurse vanish and instead she had to find a job to help ease her mother's financial burden. It would be a full year before any of the widows or children would receive their first monthly insurance cheque for the loss of their husbands and fathers.

Three of the men who were lost on the Mabel Dorothy were single: Garfield Lawrence, 20, and Henry House, 21 — both of Bay L'Argent — and Thomas Jensen, 39, of Harbour Breton. Three of the others — the 57-year-old Ralph; Thomas Bolt, 54; and Herbert Hollett, in his early 50s — were older, with nearly all of their children grown.

Chief engineer Willoughby Riggs, 46, of Stone's Cove left a wife and nine children to mourn. Six of the children were young, ranging from two months to 14 years old, and thus still living at home. To make the situation even worse, his wife, Theresa, died just two months after he was lost at sea.

Riggs had moved his family to Grand Bank early in the summer of 1955, as it was the schooner's home port and he would be able to see his family more often. Theresa, who was pregnant, had been complaining of stomach pains before the family left Stone's Cove. Her baby was born in September; that event coupled with the news of her husband's death in November caused her condition to drastically worsen. Shortly after she was airlifted from the Grand Bank Cottage Hospital to the General Hospital in St. John's, where the doctors diagnosed her as having inoperable stomach cancer. She died in January 1956.

Two of the Riggs's older daughters were married and the oldest boy was at university, but what was to become of the six younger children? The extended family members did their best; three of the Willoughby's sisters came down from Halifax, and each took a child back with them. The two older daughters, with young children of their own, also pitched in to take care of the other three.

More tragedy

But there was more tragedy to come: the aunt who had taken the baby died in March 1956 and the second eldest daughter died in January 1957.

Leroy Riggs turned eight just after the family moved to Grand Bank.

"Everything was kept from us," he said. "I was never told what really happened, only that the schooner was missing and maybe Dad swam ashore."

Leroy's older married sister, Beatrice, came down from Halifax and took him along with the baby — Willoughby Junior — back with her. The following spring he moved back to St. John's to live with his sister Vera after Beatrice died.

"I moved around so many times while in Grade Three that I attended five different schools," he said. "I was so mixed up that when I was told in January that Mom had died, I couldn't even cry."

Harvey was 10 years old when he lost both parents.

"I had a happy childhood in Stone's Cove, but that all came to an abrupt end when we relocated to Grand Bank. I saw a car for the first time and I remember being really scared at a soccer game and going to Fortune in a small bus. Then I remember being in the hospital and saying goodbye to my mother," he said.

"The last vision I had of my dad was of a bald-headed man with a brown leather jacket walking away. Later I remember being in downtown Halifax and seeing a bald-headed man walking in front of me, thinking, 'Could that be my dad?' I was 52 years old when I grieved the loss of my dad. The biggest problem I had to deal with was no closure."

Eventually two of the younger children were adopted. The youngest child, Wayne, became very successful as a writer, won many awards in journalism, and penned several plays, including Abandon Hope Mabel Dorothy.

Wayne had been adopted by a MacPhail family in Dartmouth, N.S., where he grew up. When he was still very young he has a memory of his grandfather Riggs coming to visit him there. Later in his youth the family moved to Burlington, Ont., and, according to Leroy, they lost contact with him.

"I was always asking our family about Wayne but no one reached him," Leroy said. "Then one day when I was looking in the Burlington phone book, I saw his name and called him — this was in the early 1980s. I told all my siblings that I had found Wayne and most of them then contacted him."

Leroy was then living and working in St. John's. One day when he had to go to Toronto on business he called Wayne to see if they could meet at the airport. Wayne agreed.

Reuniting with Wayne

"On arriving at the airport baggage area I spotted Wayne from a long distance," Leroy said. "I didn't know what he was wearing and didn't know that he had a beard — I just knew it was him."

A few months later, Wayne and his wife came to visit Leroy's family in St. John's.

"While there he discussed writing a play about the family. A few years later, early in the 1990s, he spent several weeks in Newfoundland, at Grand Bank, Corner Brook and St. John's researching, asking a lot of questions and gathering information — some that was new to all of us — about the loss of our father's schooner," Leroy said.

But according to Wayne, although some thin evidence and hearsay suggested the schooner had been cut down, he didn't turn up any proof, and concluded he really didn't know what happened.

He was moved to write the play because he felt the story might resonate with other folks who were also adoptees.

"I also thought it would be a good way for me to explore my own feelings about finding a new family after so many years — decades, really," he said.

"I think the thing that affected me most during my research was being in the merchant's shop in Grand Bank and seeing the papers about the Mabel Dorothy, still there in an old oak filing cabinet — I spent a long time going through those papers."

Wayne found that visit to Grand Bank to be emotionally difficult, especially the day he walked down on the wharf and was recognized by an older gentleman, who told him he looked like his father.

Leroy continued to live with his sister Vera Frampton, and became regarded as one of her children and a brother to her children. In 1960 another sister, Catherine, also came to live with Vera and her family. Vera, in Leroy's words, "supplied much of the glue that kept our family together." Some years later she self-published a collection of her memories, entitled Triumph Over Tragedy — The Riggs Family of Stone's Cove.

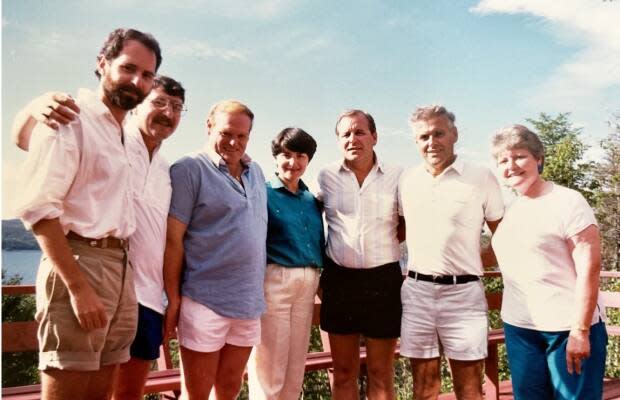

All of the Riggs children have done well in their chosen careers and have kept in touch with each other. Harvey, Frank, Newman and Leroy meet every Friday morning in downtown Halifax for a coffee, and there are plans being made for a Riggs family reunion in Prince Edward Island this summer.

The Mariner's Memorial in Grand Bank has given a form of closure to some of the widows and children of lost seamen but the emotional fallout can carry on into future generations.