So many birds are in the sky at Ontario's Long Point right now, they're showing up on radar

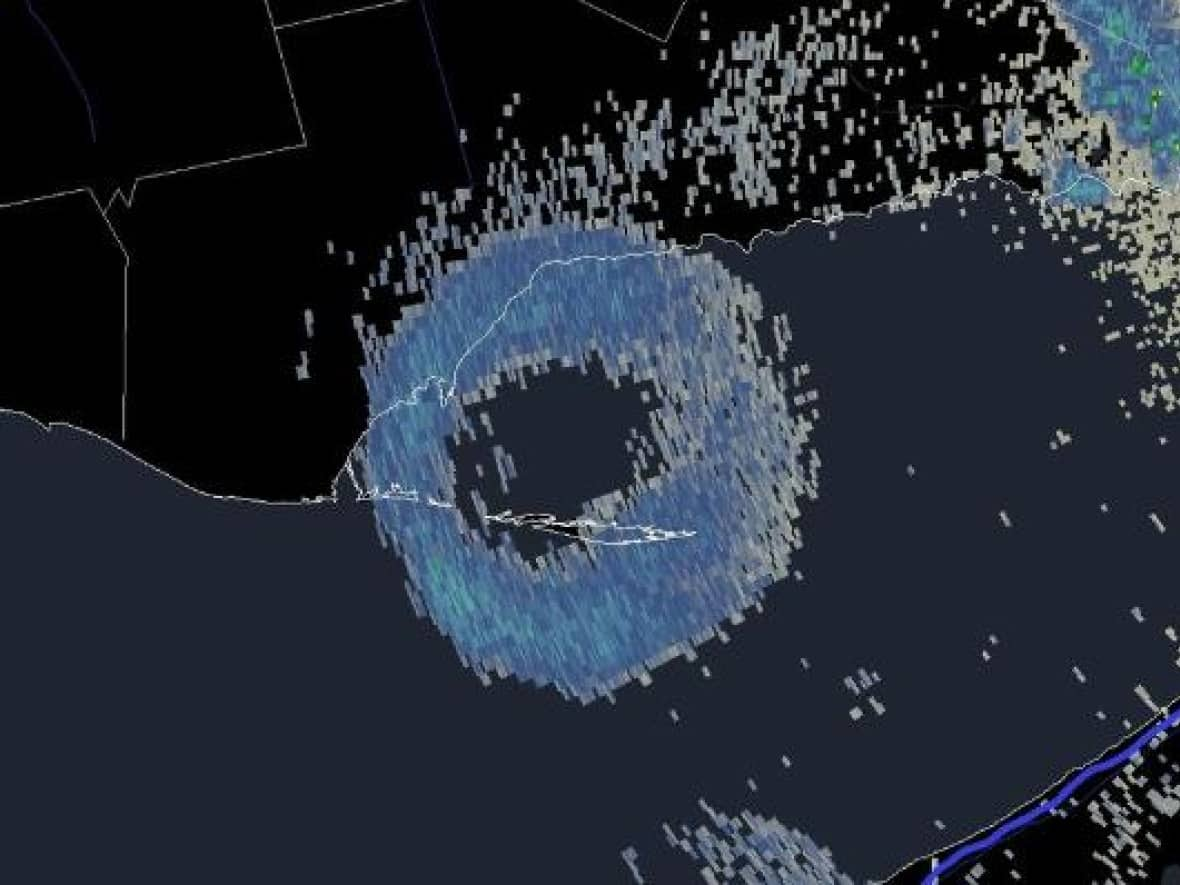

There were so many birds flying over Ontario's Long Point peninsula on Sunday that they appeared as a massive doughnut on American weather radar in Buffalo, N.Y.

The image has been captured and shared widely on social media — a sign of the annual southward migration of millions of birds that's in full swing across Canada as the arrival of shorter days and cooler temperatures signals them to take flight in search of sunnier weather far to the south.

The phenomenon is called a "roost ring." The U.S. National Weather Service describes it as "when the radar beam detects thousands of birds taking off from their roosting sites around dawn to forage for insects."

The image was posted to social media by meteorologist Corey Elder, who told CBC News by email that, while it is common to see roost rings, it's rare to see "such a perfect concentric ring."

While most people have never seen one, professional weather watchers see it quite often, according to Jim Mitchell, a meteorologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), across Lake Erie in Buffalo, who works at the radar station that captured the image.

Long Point is a UNESCO biosphere reserve

"The birds are all roosted together, and obviously when they take off, they have to spread out. It looks like a ring when they fly away, and there's so many of them, it shows up," Mitchell said.

Mitchell said the radar station in Buffalo is so sensitive, it picks up cars on the nearby freeway and flocks of seagulls scouring trash heaps at a dump south of the city. But the size and scale of the bird swarms at Long Point are so massive and dense, it registers on radar even though Buffalo is 167 kilometres away, he said.

"Long Point, that's the most pronounced one we see."

It's because Long Point is the largest freshwater sand spit in the world, and one of the most important areas for migratory birds in North America.

This sandy, narrow and uninhabited peninsula extends 40 kilometres into Lake Erie. It's so unique and rich in species at risk, it's been recognized as a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve.

"With it, is probably the largest wetland, if not, the largest wetland in the entire Great Lakes," said Stuart McKenzie. As director of strategic assets for the non-profit Birds Canada, it's his job to manage the Long Point Bird Observatory and the field work that goes on there.

Swarm is likely swallows or purple martins

McKenzie said that, given the size of the roost ring and the time of year, it's likely that barn swallows, bank swallows or purple martins, or a combination, were the birds swarming in the hundreds of thousands, roosting, moulting and fattening up for the journey on plentiful insects.

"Why it's so attractive to swallows is because of those protected wetlands; they give them a safe place to roost at night and huge quantities of food for them to forage on during the day."

The swarm is likely from across most of southern Ontario, maybe even further afield, and the birds congregate at Long Point to roost at night, McKenzie said. When dawn breaks, they leave in such large numbers that radar stations can detect them more than 100 kilometres away.

"The low end, in terms of the size of the roost, is about a hundred thousand swallows on any given night and, on the high end, it's well north of half a million.

"On radar, it gives sort of that doughnut signature, with the centre of that doughnut being the roost location as the birds disperse from the site in all directions," McKenzie said.

He said the phenomenon happens for a couple of weeks, and then one day, the birds decide they're off and they fly to the southern United States or South America for the winter.

Before they go, however, McKenzie said, to be there on the ground and see the birds congregate for yourself is a sight to behold.

"It happens very close to sunset when they begin to roost. They begin to swarm, and mix up and spend about a half-hour or 45 minutes cavorting over the wetlands moving in these large swarms.

"It's almost like a tornado or a vortex. Those swarms circle and circle, and then this vortex goes down in to the marsh, and that's when the birds peel off," McKenzie said.

When we didn't have this technology, they probably blocked out radar. It's hard to tell. - Stuart McKenzie, Birds Canada

"It seems to be in this co-ordinated fashion, and they will eventually descend into the wetlands and disappear."

It's something the birds have been doing for thousands of years, and yet we have only relatively recently possessed the technology to see it on a large scale at Long Point and similar sites, such as Walpole Island or less frequently at Point Pelee.

"For me, it's a humbling experience," McKenzie said of seeing birds whose populations have declined by 50 per cent in the last 40 years congregate in the hundreds of thousands.

"There's half a million now. It's phenomenal. What was it like 50 years ago? When we didn't have this technology, they probably blocked out radar. It's hard to tell."