It might not be the time for reparations in KC, but we need to talk about our history | Opinion

In 2021, the Chicago suburb of Evanston, Illinois, became the first American city to offer reparations to its eligible African American residents.

Now, a conservative organization has filed a lawsuit to stop the payments.

As Kansas City goes down its own road to reparations, there are lessons to be learned here.

Judicial Watch calls itself a conservative, nonpartisan educational foundation. On its mission page, it describes its actions of using open records or freedom of information laws “to investigate and uncover misconduct by government officials and litigation to hold to account politicians and public officials who engage in corrupt activities.”

On May 23, it filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of six individuals over the city’s use of race as an eligibility requirement to receive $25,000 payments. The program gives the money to Black residents and descendants of Black people who lived in Evanston between the years 1919 and 1969.

The lawsuit accuses the reparations program of violating the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

The eventual ruling on this lawsuit certainly will affect other states and cities looking to address the wrongs of slavery. Will it gut these efforts? Perhaps, because a national survey shows granting reparations isn’t a popular idea.

The history of atonement for injustice

Reparations is most widely known as a financial atonement to Black Americans whose ancestors were enslaved in the United States from 1619 to 1865, and those affected by discrimination during the following Jim Crow era. The NAACP’s resolution on reparations refers to how the enslavement and persecution of Black people in the United States has enriched the country and created disparities in income, wealth and education between Black and white people.

California was the first state to begin tackling the weighty issues of reparations. New York has followed suit. Evanston is the first city to approve the program. Boston, Atlanta and Asheville, N.C. have studied reparations. And in 2023, Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas announced the appointment of the Mayor’s Commission on Reparations to study and make recommendations. The commission has held public hearings over the past year, most recently in March.

The ordinance to establish Kansas City’s commission was written with the help of the KC Reparations Coalition. The legislation included a list from a local 2016 disparity study, which found:

White-owned firms were awarded 86% of $1.97 billion in local contracts. Black-owned firms were awarded 7%.

ZIP code 64128, which is predominantly Black, has the city’s lowest life expectancy at 68.1 years. ZIP code 64113, which is predominantly white, has the highest life expectancy at 86.3 years.

More than 75% of white residents are homeowners. Fewer than 45% of Black residents are homeowners.

The median household net worth of white families is $188,200 and the median net worth of Black families is $24,100.

In 2020, Black drivers were 23% more likely to be stopped by the Kansas City Police Department than white drivers.

The ordinance reads, in part: “The City of Kansas City’s past actions to support and defend the institution of slavery and segregation era human rights violations has led to substantial disparities in wealth, health, homeownership, criminal justice and educational outcomes for Black Kansas Citians as compared to non-Black Kansas Citians.”

The Star reported on the Black Audit Project in March, a separate initiative to gather stories from Black residents on injustices in the community. Its hope is to aid the commission when it makes recommendations.

Despite all this action, it doesn’t appear that Kansas City will move quickly with its own reparations program, especially now. But a new book from a Kansas City author shows how the disparities of slavery continue today.

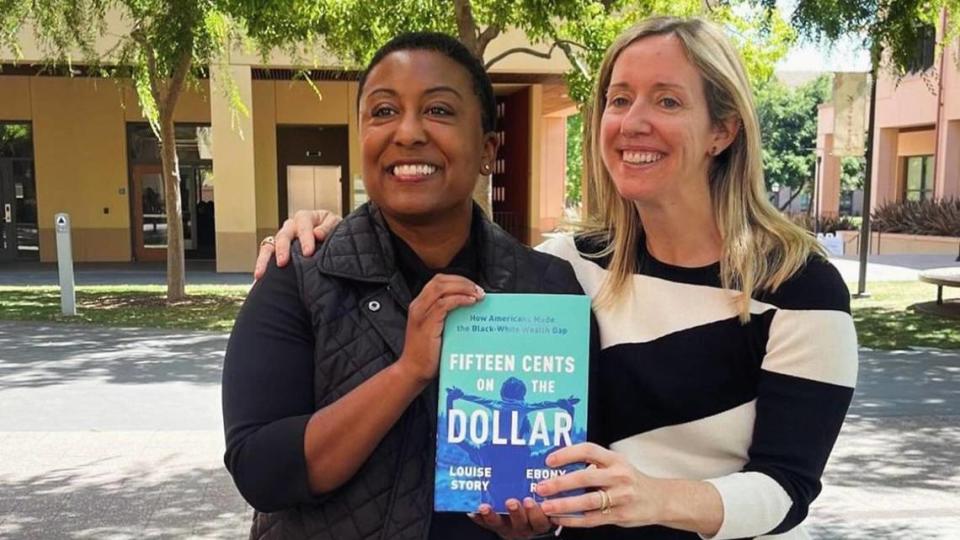

Ebony Reed and Louise Story wrote “Fifteen Cents on the Dollar: How Americans Made the Black-White Wealth Gap.” The book explores how slavery, redlining, banking practices and other economic discrimination led to the titular gap. Story and Reed describe that typical Black families have 15 cents in generational wealth compared to one dollar of the typical white family’s wealth.

They spoke to hundreds of people in researching the book, but focused on seven individuals — from poor to middle class — whose generational wealth has been affected by economic discrimination.

In the preface, Reed, who is Black, discussed her own generational wealth history: In college, she had to take out college loans, while Story, who is white, did not. Reed and her fiancé, who is also Black, decided to move to Kansas City in part to better steward their East Coast salaries while living in the Midwest. The 2008 financial crisis affected Reed during a short sale of her home.

“The courts can argue about what’s legal with these policies,” she told me, “but the reality remains that the typical Black family has 15 cents for every $1 of wealth held by a typical white family.”

Compensation with land, money unpopular

The Pew Research Center showed how Black and white Americans don’t agree on reparations. Not even close. The 2022 study found only 3 in 10 people say descendants of people enslaved in the U.S. should be repaid in some way, “such as given land or money.” About 7 in 10 say these descendants should not be repaid.

When you break it down by race, the statistics are startling. Only 18% of white Americans agree with reparations, compared to 77% of Black people surveyed.

I have to wonder what can account for the divide. Because I don’t believe that everyone who disagrees with reparations is prejudiced, I think it’s a lack of understanding how generational wealth is tied to the horrific beginnings of Black Americans’ history in America.

Is prejudice woven in somewhere? Perhaps. When I first heard about the reparations and later, the lawsuit, I found its location interesting. Despite it being a college (read liberal) town, it amazed me that Evanston was first to approve reparations.

I attended college at Northwestern University there, and growing up in Chicago, I always heard about intolerance in those northwest suburbs: the Nazi marches in Skokie, Illinois, and later, the Ku Klux Klan, for example.

As Judicial Watch makes its move to kill the Evanston program, we must look at the organization itself, which has a staff and board member connected to white supremacy.

While there is no direct evidence that Judicial Watch itself is a white supremacist organization, its director of investigations and research was tied to the Oath Keepers, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center’s HateWatch:

“Christopher Farrell, the director of investigations and a board member at prominent right-wing nonprofit Judicial Watch, was included on a membership roster of the antigovernment extremist Oath Keepers, according to leaked documents reviewed by Hatewatch.”

HateWatch found Farrell’s name twice in documents, but Farrell’s representatives said he only gave a small donation and purchased a T-shirt.

SPLC also points out that while Judicial Watch has no known partnership with the Oath Keepers, the organization pushes conspiracy theories and has partnered with the far right, including Donald Trump’s former White House chief strategist, Steve Bannon.

Even if you find reparations troubling and believe it does violate equal protection for everyone, I’d prefer a case with no racist implications. Is that possible?

Black-white wealth gap ‘dynamic’

If passed nationally, will reparations ultimately close the wealth gap? In the book “Fifteen Cents on the Dollar,” researcher Ellora Derenoncourt of Princeton University posits an amount — $267,000 per person — would close the gap, “but only for a short time.”

Authors Story and Reed call the Black-white wealth gap “dynamic,” with many variables, and believe that a one-time influx of cash wouldn’t make a meaningful difference to the wealth gap.

“If Black Americans were given an influx, the Black-white wealth gap would remain if it was still more difficult for Black people to get loans than it was for white people; if Black people were still arrested more than white people for the same alleged offenses; if Black people were promoted at work less than similarly talented white people; if Black people invested differently from white Americans; or, if Black people could not get access to the same types of relief as white Americans.”

Another thing to consider is timing. Is now, in 2024, with a presidential race that could spell the downfall of democracy, the right time to plead this cause?

We know a majority of Americans dislike the idea. There is a chasm between Black and white people on reparations. Would pushing this idea now push Trump into the White House? Should we wait until 2025 and start fresh?

Or, if you are a believer in reparations, is the idea of “not the right time” just an excuse?

Listen, I don’t expect to be paid anytime soon, and even if I were, I’d like to think I would use the money to help worthy causes.

Like Reed and Story, I do think reparations are worth studying, if nothing else, to help people understand this financial gap between Black and and white Americans.

It’s not laziness, ignorance or a cultural inability to succeed. It’s history.