Nearly 70 years later, CFB Gagetown expropriation still resonates

Even though she was a young child at the time, Connie Denby remembers Labour Day of 1953 as if it was yesterday.

It was the day her family left Upper Hibernia, a New Brunswick community that no longer exists, having been swallowed up by CFB Gagetown.

"It was raining so hard and we were all crying," Denby said.

The family was moving to a new home built in nearby Queenstown, and she was supposed to start Grade 2 at her new school the next day.

"Everyone was crying and upset, and we put as much of the personal belongings and furniture in the back of a logging truck with sideboards that we could get."

"It was traumatic. Even though at a young age, I still remember it well because so many people were going through the same thing."

Her family was one of about 750, living in 20 communities, who were forced out of their homes by the biggest expropriation in New Brunswick's history.

Places with names like Dunn's Corner, Coote Hill, New Jerusalem, Clones, Armstrong's Corner and Summer Hill would all disappear along with Hibernia.

Denby said her hometown, like the others, was a close-knit community.

"Most of the men worked in the woods in the winter and did some farming in the summer," she said, "with just a few milk cows and a team of horses and what have you. But everybody pitched in."

"There was a community hall and churches and the schools … there was a general store that also doubled as a post office, and it was a gathering place."

"And the lady that lived there one time — we had a copy of a five-year diary that she had with not one word of gossip in it — but she recorded every day what the temperature was, what the weather was like, who stopped by, who might have been there for dinner," Denby recalled.

"I don't know how the lady kept up. Almost everybody that came stayed for dinner or stayed for tea. … People looked after one another and if there was a hardship, they were there to help."

But in July 1952, that quiet rural life would change dramatically.

'Boy scout camps'

Ottawa had been in a search of a national training area since the end of the Second World War.

The army had struggled to train large formations at home in what one officer said at the time were "overgrown boy scout camps."

It was such a problem, Canada had to send units destined for Korea to a large U.S. base to train.

New Brunswick had lobbied hard to be home to the new base, to create what would be at its outset the sixth largest employer in the province.

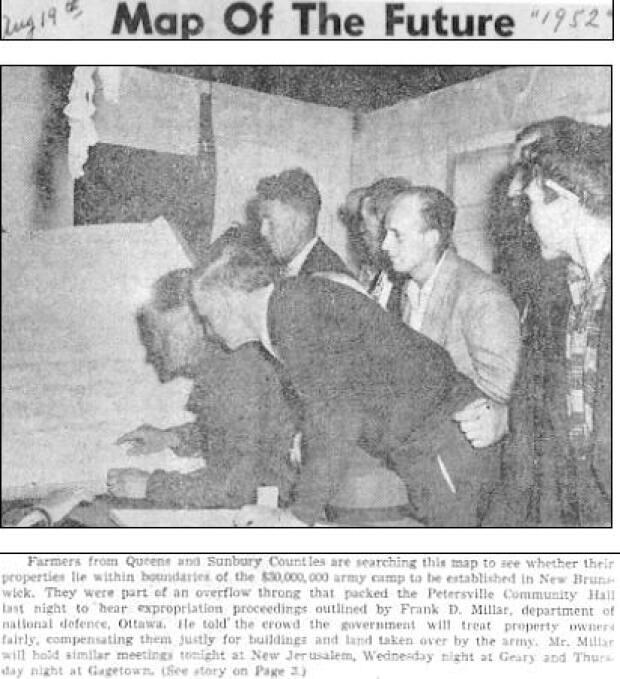

When the final decision was made, the people who lived in that area of the lower St. John River Valley were shocked to find out their homes were in the army's crosshairs.

The late Bill Clarke was then a veteran of the war and newly married with a young family living in Hibernia.

Speaking to CBC News in 2003, seven years before his death, he described the Department of National Defence buyer, a man named Frank MIllar, as a "very smooth talker" and a "hard customer."

"They found the people that were maybe willing to take a settlement and go, and they settled with them, you see," Clarke recalled, " Well, then this made it inevitable that this was happening, so then they started pushing into the others."

Some resisted, at least for a while.

"A few did put up a fight and went to Ottawa to try and get information and persuade the powers that be," Denby said. "But it just happened and certainly some people were happy to move because some people were maybe not as prosperous as others."

Denby said Ottawa was able to take advantage of a populace that had deep Loyalist roots and had just come through the hardship of a war — people who were generally trusting of government.

"It's just amazing that it happened. It would never happen today, for sure … there'd be an uprising, shall we say."

A reporter from MacLean's magazine visited the new base in 1954 and described what he saw.

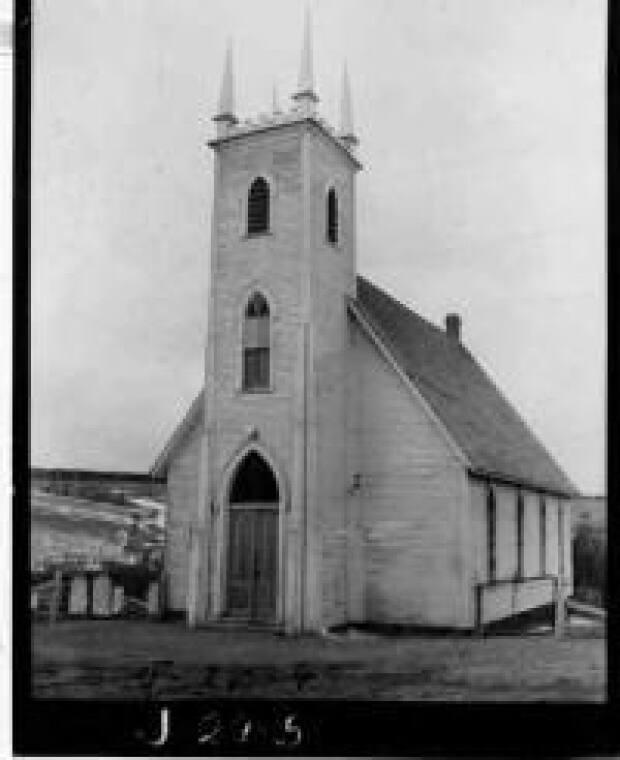

"On it hundreds of farms, tilled since the days of the United Empire Loyalists, lie deserted. … Dirt roads wind through dark woods past ghost villages whose people have sold out to Ottawa and moved on. Numerals painted on each empty house, each school, church, barn and privy signify that the army has taken over."

In what has been described as the most complicated land deal in the province's history, the army paid out almost 1,100 settlements.

The army also agreed to maintain nearly 30 cemeteries and to allow families to return for special occasions such as reunions and funerals.

Bob Johnson, who lived in New Jerusalem until the age of 11, said the attachment to the area hasn't gone away.

"It's always there," he said. "It's home. And people say, 'Oh, I'm going out home.' It doesn't matter where they live."

"I was visiting a family just recently, and they were living on the same ground, an original grant, that their grandfather and great-grandfather had had.

"And I said, 'You know, the one thing I miss about New Jerusalem not being there anymore is the fact that we don't have that ancestral place to go to anymore.'"

It's the day of the annual July 12 picnic at the Loyal Orange Lodge Hall in Queenstown, just on the outskirts of the base. This has become a traditional annual meeting place for people who once lived there.

The hall was moved to Queenstown from the base in 1954. It was in Dunn's Corner, where it was known as the No. 4 Hall.

On the wall inside, there's a photograph of a dance at the No.4 Hall. Based on the clothing worn by the dancers in the photo, it's likely from the late 1940s or early '50s.

On the opposite wall, there's a large map of the base property, with the former communities marked.

The map is surrounded by black and white photographs of buildings from those communities, buildings that are long gone now.

On this warm Saturday, about 30 members of the Base Gagetown Community History Association have gathered before the picnic supper is set to begin to talk about the future of the group.

Formed in 1998 by former residents of the area, it has spent more than two decades gathering photos, documents and family histories.

But nearly 70 years since the expropriation forced them from the place they called home, the number of people who actually remember those events is dwindling.

The group's Facebook page is mostly postings of obituaries these days.

"In 2006 there were 217 members and in 2022 we're down to 83 members," Denby, who is president of the association, tells the assembled group.

She's one of the youngest, at 76 years old.

Denby believes the time has come to formally shut down the association.

"I certainly have mixed feelings," she said. "But people are certainly aging . … And as sad as it will be to lose that social connection, I sort of feel it's about time that we have to perhaps move on."

That leaves the question of what to do with the material the group has gathered.

"There's many, many plastic totes full of information.," Denby said. "And we seem to perhaps maybe add more each year as we had a booth at the Queens County Fair every September … and we just kept amassing more information and photographs and what have you.

"And it's going to be quite a task to sort through the material and save what is important and perhaps even think about discarding some of it."

The hope is the provincial archives will be the eventual home of that material, and that the archives might also take over operation of the association's website.

Provincial archivist Fred Farrell said the group has been in contact, and the archives are interested in taking on the material.

"They did a wonderful thing in acquiring this material, and they did it probably better than any outside agency could do," Farrell said.

"People have to have confidence in you to give you this stuff. And because they knew these people, they were, you know, back in the day, they were their neighbours or their parents were their neighbours, and so they had that confidence."

Farrell said if the archives take on the material, his staff will likely have a big job sorting through what is valuable and what isn't, and will rely on the association for help.

"When the organization does it, sometimes they make links between things that aren't obvious … because they know the stuff so well that they make those connections."

Even if the association disbands, both Denby and Johnson are confident the remaining former residents will still return for reunions at the Queenstown picnic, or for Remembrance Day ceremonies held on the base property.

"The people love the land. They love their neighbours and any opportunity for a gathering," Denby said.

"People still make the effort, if it's a funeral or if it's a social event of some sort and an anniversary, people will go out of their way to get to that function, to see their former friends and neighbours."

Johnson said the connection to the area runs deep.

"Yeah, it's home. And here I am, 80 years old, just about. And it's home, even though I've lived in many, many places, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, since.

"But that's home. And sometimes when I dream, that's where I am. Strange, isn't it?"