Patient 'rotting alive' from bedsore dies, Burlington hospital launches action plan

Bob Wilson, whose family said he was "basically rotting alive" from a bedsore at a Burlington, Ont., hospital, has died at age 77.

Wilson was in palliative care when he died Saturday, according to his daughter Linda Moss, who said doctors and the coroner told her his primary cause of death was a bedsore infection that got into his bones and blood.

"We miss him a lot," she said. "But he can finally rest in peace and at least there will be no more hospitals."

CBC News reported on Wilson's case in May. The family's advocacy about what happened to him led to an apology from Joseph Brant Hospital. It also kickstarted a hospital investigation and the creation of a bedsore action plan.

Moss says the past six months have been a trying time for the family as they've been forced to learn about bedsores — also known as pressure ulcers — while watching her father "disintegrate in front of [their] eyes."

Wilson was admitted to the hospital in November after he fell and suffered a brain injury.

As the months passed, Moss says, the former golfer and bowler started to show signs of improvement, but his recovery seemed to stop suddenly in February and the family couldn't figure out why.

At the end of April, when he was ready to be transferred to nearby Hamilton General Hospital for surgery to reattach part of his skull, Wilson's family was told the surgery couldn't happen because he father had an infection.

Then they were shown a picture of the wound.

"It was ... so massive. It was black, dead, rotted skin," said Moss. "He was basically rotting alive, and we had no idea."

Hospital publicly publishing bedsore rates

Wilson's family met with Joseph Brant's CEO last week, and Moss said he apologized for what happened and pointed to a "communications breakdown" as one of the factors that led to her father's condition.

Moss said the hospital is working on a "ton of changes" and wants to work with the family to raise awareness about bedsores.

"I'm happy they are taking further action to change protocols and procedures so more families or patients that come into that hospital are getting the care ... they need," she said.

A spokesperson for the hospital said staff "extend sincere condolences to Mr. Wilson's family."

After the bedsore was discovered, Joseph Brant president Eric Vandewall personally apologized to the family and promised to update them on an investigation into his care.

After what happened to Wilson, Vandewall said Joseph Brant will voluntarily publish the rates of hospital-acquired pressure ulcers and surgical-site infections on its website, starting this month.

That bedsore action plan also includes meetings with Wilson's family and that of another patient, reviews of their cases, and quarterly Prevalence and Incidence Studies to "increase surveillance and prevention of hospital-acquired pressure wounds."

Sharing the story of a 'silent killer'

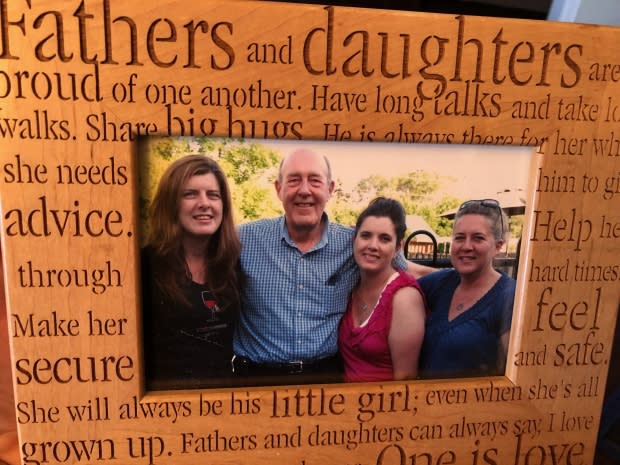

Following her father's death, Moss and her sisters took his story to the media, hoping to start conversations about ways to prevent bedsores and a family's role in patient care.

In recent weeks, they've heard from families who thought they were suffering alone. Now no one is ignoring bedsores any longer, said Moss.

"It's a silent killer and now it's been brought to light. Hospitals are taking note."

Moss said her family's story has become a learning experience for many. Now they're calling on anyone with a loved one in care to educate themselves about the risks, advocate for their well-being and keep communication lines with caregivers open.

It's a message they plan to continue sharing, even as they arrange their father's funeral.

"That's been a blessing and some sense of relief for us knowing our father didn't pass away in vain. His story and his legacy will continue on and help more people. That's amazing."