Pope Francis, in Iqaluit visit, asks forgiveness for residential schools

Pope Francis wrapped up his Canadian visit on Friday evening in Iqaluit with an outdoor public speech before a crowd of both admirers and critics, and again offered an apology for the "evil perpetrated by not a few Catholics" involved in Canada's residential school system.

"I want to tell you how very sorry I am," he said.

The roughly four-hour visit — which went more than an hour longer than planned — included private meetings with residential school survivors, as well as public performances by traditional singers and drummers. It culminated in the Pope's public speech outside a local elementary school.

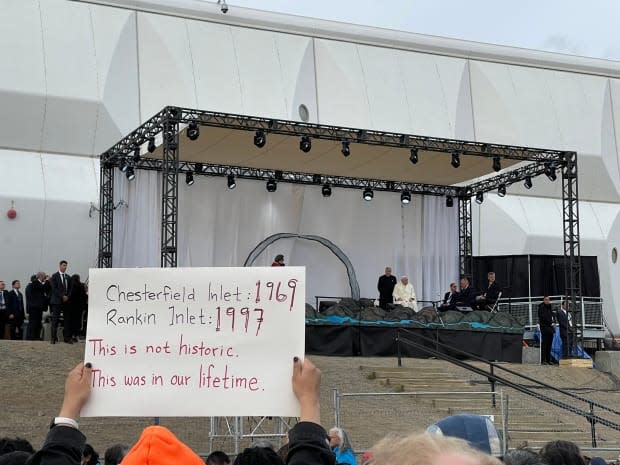

There were tears and applause when the Pope finished speaking, with some people shouting "we love you!" to the pontiff. Elsewhere in the crowd, some spectators held signs of protest about residential schools and the Doctrine of Discovery.

The Iqaluit trip marked the first-ever papal visit to Canada's newest territory, and for some, a potential turning point in a fraught century-long relationship between the Catholic Church and the Inuit of Canada.

"I'm very happy Pope Francis is able to come here and am happy that I'm able to see this," Ooleepika Veevee told CBC News in Inuktitut on Friday. Veevee was in Iqaluit Friday, and two days ago she was also in Quebec City for the Pope's visit there.

"He came all the way from Rome to come and apologize," she said.

Raigelee Alorut, also from Iqaluit, told CBC News in Inuktitut that she was there to honour her parents and other relatives "who are not here anymore." She said her parents were sent from Iqaluit to Churchill, Man., and though they eventually returned, their lives were forever changed.

"They never talked about anything, of their experiences. Because they were hurting inside," Alorut said.

"I've been affected, my children, and also my grandchildren. As it's an intergenerational trauma. Many who've never gone to residential school are also affected by this."

The papal plane arrived in Iqaluit at about 4 p.m. ET and the pontiff was greeted by local dignitaries including Nunavut Premier P.J. Akeeagok and Commissioner Eva Aariak.

Crowds of people gathered outside Nakasuk school soon after the Pope's arrival. They listened to drummers and throat singers on stage, while the pontiff met privately with residential school survivors inside.

Among those who spoke privately with the Pope was survivor and former Nunavut commissioner Piita Irniq, as well as Tanya Tungilik, who described how her father Marius Tungilik was abused as a student at residential school in Chesterfield Inlet, Nunavut, and how that experience haunted his life and family for years to come. Marius Tungilik, who died in 2012, was among the first survivors in Nunavut to publicly tell their story and push for the church's accountability.

After the private meetings inside, the Pope moved outside to participate in a public event. Sitting on stage before a large crowd, he watched singing and drum performances before delivering his address.

After the speech, the Pope sat alongside Gov. Gen. Mary Simon for some final greetings before he was taken back to the papal plane to depart for Rome.

'Start heading forward'

"Once the Pope apologizes, we must find a way to move from that. To start heading forward," said Mary Ajaaq Anowtalik, an 84-year-old elder from Arviat, Nunavut, speaking in Inuktitut, ahead of the papal visit. Anowtalik was part of a throat-singing performance before the Pope.

Anowtalik sees the visit as an opportunity for the Pope to "start on a different path."

"In the old days, if there was someone that needed guidance, they would be brought to the elders, for life skills, guidance," she said, through a translator.

Anowtalik's comments hint at a dynamic shift that's happened in recent years amid conversations about colonialism, reconciliation, and the legacy of residential schools. Where once the church and its leaders presented themselves as spiritual guides for Indigenous people, they're now seen by some in Nunavut as the ones needing guidance.

"I just want to hear him say that the church is open without prejudice for everyone," said Aksaqtunguaq Ashoona, who will be among a group of Inuit greeting the Pope when he deplanes in Iqaluit.

"That's all I want to hear him say. Like, apologize and reopen the church gates."

There is a small Catholic parish in Iqaluit, and the city is one of 16 communities in the Canadian Arctic with a Catholic population. Some communities have permanent missions with a priest or a sister, others are attended by visiting priests or sisters.

Speaking to the Vatican News recently, Iqaluit's Catholic bishop Anthony Wieslaw Krótki acknowledged that Iqaluit does not have a large Indigenous Catholic population, and that more Inuit in the city are Anglican. Iqaluit was chosen for the papal visit simply because of logistics, he suggested.

But the church's historic legacy looms large in many parts of the territory.

The first permanent Catholic mission in the eastern Arctic of Canada was established on the western shore of Hudson Bay, at Chesterfield Inlet in 1912 by Arsène Turquetil.

Decades later, the students' residence named for him in Chesterfield Inlet — Turquetil Hall — would become notorious as a site of physical and sexual abuse of young Inuit. Between 1955 and 1969, hundreds of children were sent there, far from their homes and families. Many other Inuit children were sent to the equally notorious Grollier Hall, in Inuvik, N.W.T.

Some residential school survivors will be in Iqaluit on Friday, including former Nunavut commissioner Piita Irniq, who will be part of the official delegation greeting Pope Francis. According to a draft itinerary of the papal visit, Irniq will have about five minutes to testify before the Pope.

The Pope will spend about two and half hours in Iqaluit, arriving just before 4 p.m. ET and leaving at around 6:20 p.m. ET.

Support is available for anyone affected by residential schools, and those who are triggered by the latest reports.

The Indian Residential School Survivors Society (IRSSS) can be contacted toll-free at 1-800-721-0066.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former students and those affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.

In addition, the NWT Help Line offers free support to residents of the Northwest Territories, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. It is 100% free and confidential. The NWT Help Line also has an option for follow-up calls. Residents can call the help line at 1-800-661-0844.

In Nunavut, the Kamatsiaqtut Help Line is open 24 hours a day at 1-800-265-3333. People are invited to call for any reason.