Is rap on trial? How lyrics can be used against rappers in courtrooms

No one believes that country music legend Johnny Cash shot a man in Reno, just to watch him die.

When Cash in 1968 released “Folsom Prison Blues,” a ballad about shooting and killing a man for no apparent reason, it was deemed controversial by some. The song was largely recognized for its dark, macabre humor — part of the Grammy-winning country music rebel’s famed songwriting style.

It’s an example used by advocates to illustrate the contrast in how the genres are treated in the justice system. When a rapper faces trial, it’s not uncommon for prosecutors to label their lyrics as an accurate detailing of events.

The use of lyrics in the courtroom has again surfaced in the ongoing high-profile trials of two rappers in Florida and Georgia. The prosecutions of YNW Melly and Young Thug.

The lead prosecutor in YNW Melly’s double murder case recently filed court documents that show the state plans to admit 55 songs, four album covers and 18 audio files into evidence. Among the proposed evidence is double platinum song “Murder on My Mind,” which features a grim retelling of an unintentional homicide over a blend of emotional piano riffs and hip-hop beats.

READ MORE: Could lyrics be used against YNW Melly in double murder retrial? Prosecutors will try

Throughout Melly’s first trial, which ended in a hung jury, the rapper’s persona as an artist was a prevalent theme in evidence and testimony presented. Melly was caught on surveillance video leaving a Fort Lauderdale recording studio with two of his childhood friends, both aspiring rappers with the YNW collective, just before they were gunned down.

While prosecutors shied away from quoting lyrics in Melly’s first trial, references to the Florida rapper’s blossoming music career, lifestyle and financial success emerged. The artist, whose real name is Jamell Demons, was often referred to as “Melly” during the trial.

Hip-hop is at the heart of Grammy winner Young Thug’s case. Prosecutors are attempting to prove that Thug is a gang leader cosplaying as a rapper and that his record label YSL, Young Stoner Life or “Young Slime Life,” is a criminal enterprise. They have been dissecting the artist’s lyrics and citing them as evidence that he violated the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act.

Hip-hop lyrics have, for years, been weaponized in U.S. courtrooms. As rap celebrates its 50th anniversary, the genre also marks a lengthy history of having its artistic expression viewed through a criminal lens in the justice system.

There are almost 700 cases in which rap lyrics have been quoted in courtrooms since the 1990s, according to professor Erik Nielson, who has led the Rap on Trial project for a decade. The documented cases are the “tip of the iceberg,” Nielson says, because they are mainly the ones that go to trial.

“The fact that we’ve identified 700 really ought to get people’s attention because you definitely should be adding some zeros to that,” he said.

The average defendant in such cases is usually a Black or Latino man between the ages of 18 and 25. Florida has the second highest number of rap-related cases, only trumped by California, which has since banned the use of lyrics in trials under most circumstances.

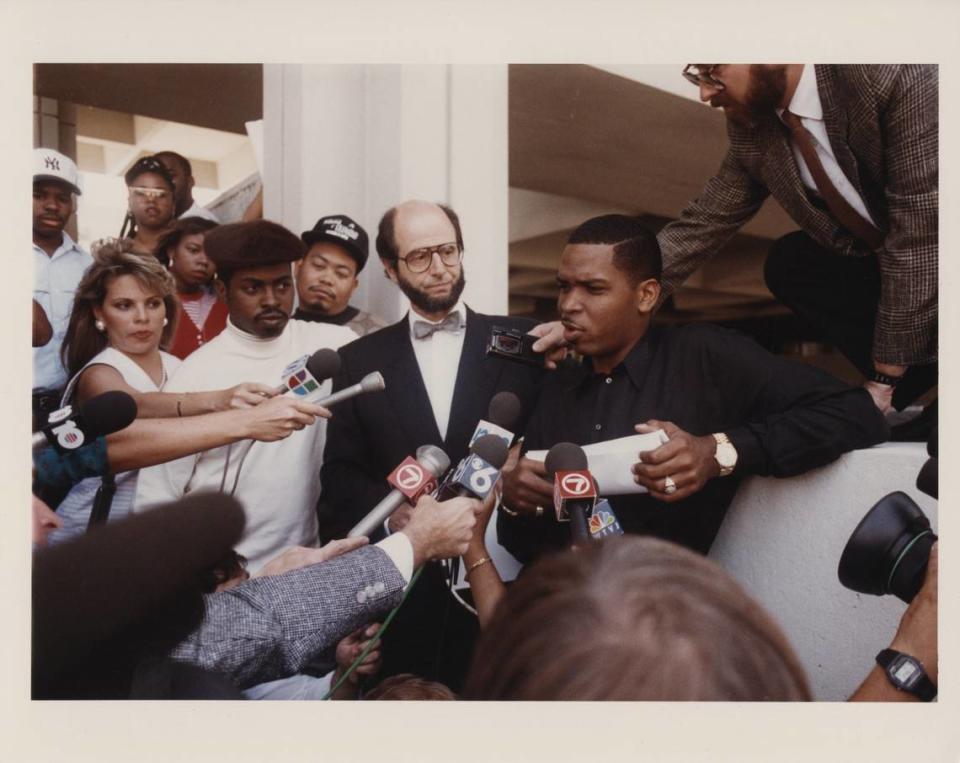

In one of the first prominent examples of rap lyrics entering a courtroom, Miami-based 2 Live Crew had their risqué, over-the-top music banned in South Florida in 1990.

Prosecutors quoted the group’s lyrics in a criminal trial that ended with a jury finding the artists, including rap legend Uncle Luke, not guilty of obscenity.

Three decades later, the criminalization of rap continues to be a reality, and not just in the United States. In the United Kingdom, more than 240 people — mostly young Black men — have had their music used against them since 2020.

While some states have taken action to curb the practice, others, such as Florida, grant prosecutors and judges discretion as to whether to quote lyrics or not at trial.

Are lyrics weaponized?

There are three main ways prosecutors approach rap lyrics in court cases, said Nielson, a professor at the University of Richmond and a co-author of the 2019 book “Rap on Trial: Race, Lyrics, and Guilt in America.”

▪ As confessions, if written after the crime

▪ As proof of motive or intent, if written before the crime

▪ As threats, when the lyrics are viewed as the crime

The most common tactic is for prosecutors to point at lyrics as evidence of some underlying crime, said Nielson, a scholar in Black creative expression who began researching the intersection of hip-hop and the criminal justice system in 2012. If a defendant is charged with a shooting, for instance, a prosecutor will likely dig into their music for lyrics that mention guns and shootings.

The least common approach is when the lyrics are considered the crime, seen as a threat toward others. True threats, a form of speech that leads someone to believe they will be seriously harmed, aren’t protected by the First Amendment. Only about 2% of rap-related cases involve white defendants, and the bulk of those concern lyrics as threats.

Prosecutors sometimes get creative with how they approach rap lyrics, Nielson said. Gang experts, for example, frequently dissect lyrics in court — allowing prosecutors to link a gang affiliation to a crime through a gang enhancement, which could get a defendant more time.

Nielson testified in a death penalty sentencing in which prosecutors brought in lyrics to argue that the defendant was smart enough to memorize lines despite his IQ being below average.

“Usually, they use the lyrics to make these guys look like stupid savages,” Nielson said. “But prosecutors are clever and so in this case, they actually use the lyrics in order to establish his intelligence so that he’d be fit for execution.”

In front of a jury, hip-hop lyrics can activate stereotypes about the genre and the artists, who are mainly men of color, said Charis Kubrin, a professor of criminology, law and society at the University of California at Irvine.

“If it wasn’t effective, we wouldn’t see as many cases as we see where this is happening,” she said.

Kubrin, who co-authored a legal guide that provides tips for lawyers to counter lyrical evidence, has also been testifying as an expert witness in rap-related cases since 2011.

She said her testimony isn’t to argue for a defendant’s innocence. On the stand, she tries to provide examples of very similar — if not identical — lines from famous rappers’ songs.

“My goal is simply to not have prosecutors use lyrics in a way that bamboozles the jury into believing the claims that the prosecutor is making, which is that if someone could write these raps, they could do these things,” she said.

this video is so funny bro was lying for no reason pic.twitter.com/Y5Iug3j3iM

— kira (@kirawontmiss) April 24, 2023

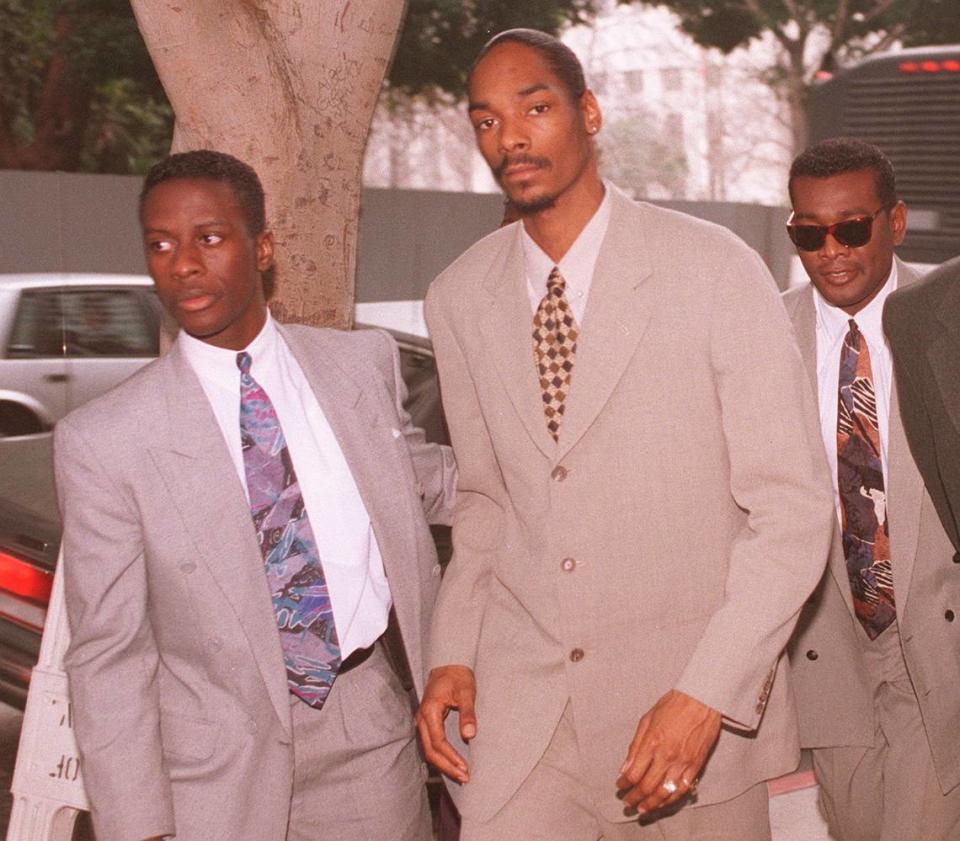

Nielson says playing a music video in which a defendant is swearing, covered head-to-toe in tattoos and waving weapons easily prejudices a jury, even as the defendant sits feet away in a suit and tie.

“What you’re doing is compromising that defendant’s right to a fair trial by using a fictional persona as somehow evidence of the actual defendant’s guilt or motivations,” he said.

Why the focus on rap?

Hip-hop was birthed in inner cities and urban areas that have been criminalized and overpoliced, which has contributed to how it is used in courtrooms, said Donald Jones, a law professor at the University of Miami and author of “Fear of a Hip-Hop Planet: America’s New Dilemma.”

Rap is a way out for many. Artists, equipped with their imagination and hopes for the future seek to envision a world beyond what they’ve experienced in growing up, Jones said.

“They create a ... universe in which they affirm their dignity and identity,” he said. “It’s a powerful, revolutionary art form, which has everything to do with living out identities ... that are cultural and political at the same time.”

The genre rebels against their reality, he said, with rappers projecting personas that are “large and in charge.”

“Hip-hop artists in lyrics are much like a film writer, or novelist,” he said. “The genre of hip-hop requires you to create a character which expresses the values of street culture.”

Jones says race is at the center of the judicial system’s attack on hip-hop. Black art hasn’t been viewed — or respected — as art for most of history. Hip-hop has even been called “Black noise.”

“Hip-hop represents the apotheosis of otherness, of evilness, of badness, of dangerousness,” he said. “It means something different to be Black in south-central LA than it would to grow up in Coral Gables.”

What do defense attorneys think?

For years, Brad Cohen has been shielding his clients from their lyrics being used against them in state and federal courts across the U.S. The South Florida-based defense attorney has represented dozens of rappers, including Drake, Lil Wayne and Kodak Black.

“When it comes to rap lyrics, everyone believes whatever is in [them],” he said. “You will find, very infrequently, if any other artist gets charged, that they would use their medium of art against them.”

However, Cohen said he believes most judges will prevent prosecutors from quoting lyrics unless they refer to a specific weapon, location or time associated with the crime.

But that’s not always the case. Quoting lyrics, Cohen said, is a useful weapon because it easily helps prosecutors “dirty up the defendant.”

While using lyrics is a growing strategy, Nielson said some courts are starting to become weary of the art form as evidence. He highlighted how, after his testimony, two Arizona federal court judges ruled that rap lyrics wouldn’t be allowed in a trial.

“Those types of decisions in the past would have been very rare,” Nielson said. “But I do think that they will start to set precedents for future decisions.”

Much of the practice, Cohen said, preys on the preconceived notions about the lifestyle in the hip-hop world. That’s why, he said, rappers have been targeted for years.

“They’re hoping that a jury will be like: ‘OK, this is a rapper. He must be carrying a gun or he must be doing illegal activities.’”

Are prosecutors divided?

Young Thug’s music is shaping up to be key evidence in his ongoing trial, which centers around whether or not his record label YSL is a criminal enterprise. Atlanta-area District Attorney Fani Willis staunchly defended using the rapper’s lyrics against him at a 2022 news conference.

“If you decide to admit your crimes over a beat, I’m going to use it,” she told reporters. “I have some legal advice: Don’t confess to crimes on rap lyrics, if you don’t want them used. Or at least get out of my county.”

A 2004 guide written by the American Prosecutors Research Institute sheds light on how prosecutors approach the practice in gang cases. The guide argues that the “most crucial element of a successful prosecution is introducing the jury to the real defendant” and urges prosecutors to use photographs, letters, notes and lyrics to uncover the “real defendant.”

By the time the jury sees the defendant, “he will have taken on the aura of an altar boy,” the guide says, though the “real defendant” is a “criminal wearing a do-rag and throwing a gang sign.”

But not all prosecutors are gung-ho about rap as evidence. Melba Pearson, a former prosecutor and director of Prosecution Projects at Florida International University, has never tried a case using lyrics but said she would approach them carefully, if she did.

A prosecutor should listen to the music, read the lyrics and compare them to evidence to see if — and where — there’s overlap, she said.

“All of those nuances give you more of a picture of what the song is about,” Pearson said.

Hip-hop in the pre-social media world, Pearson said, used to be referred to as the “Black CNN” because it reported about conditions in marginalized communities around the country. But the genre, she said, has morphed into a lot of bravado.

“It became less, in my opinion, about current events ... versus now more so, bragging about being involved in these instances,” she said.

However, just because an artist gets on a track and says something doesn’t mean it’s true, Pearson said.

“If there is not enough overlap, I would refrain from introducing it because there is very much a danger,” she said. “You have to be conscious of issues of race.”

When hip-hop lyrics emerge in courtrooms, jurors’ biases may surface. That’s why Pearson said prosecutors should question potential jurors about their attitudes toward rap, if lyrics may play a role in the proceeding. A prosecutor should want the jury to make a decision based on the facts and evidence presented — not due to some of their preconceived notions.

“You don’t want people coming on and assuming just because you are a hip-hop artist that you must be guilty of murder,” Pearson said. “That’s not justice.”