Case of rape victim told to return later for test at Fredericton ER prompts review by Horizon

A Fredericton woman is still in shock after she went to the local hospital's emergency department to get a sexual assault forensic examination performed and was told to schedule an appointment for the next day.

The woman, whom CBC News is not naming, says she was told no one was on staff or on call that night at the hospital who was trained to perform the exam.

That response by staff at the Dr. Everett Chalmers Regional Hospital has now triggered a review of how Horizon Health Network's sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) program is administered, said Horizon interim CEO and president Margaret Melanson.

The 26-year-old victim said she was told to go home overnight, not shower or change and to use the bathroom as little as possible, to help preserve any evidence.

"I just really wanted to not have to preserve my body in the state that it was in for another 12 hours," she said in an interview. "So I guess I was feeling like I was being asked to sit in that experience. Like, I could smell him on me."

It was only after she called police for advice about what else she could do, and an officer intervened, that the hospital called in a nurse to help her, she said.

As serious as a gunshot wound, police said

"No woman who has been raped should ever be told to come back tomorrow for help after finding the courage to reach out for help," the woman said.

She's decided to speak out about her experience, she said, to help make sure it doesn't happen to anyone else.

The assault happened in August on the New Brunswick Day long weekend, when she went on a date with a man she had met online.

She drove herself home around 10:30 p.m. and decided to call the Fredericton Police Force to ask what she should do when she "saw all the blood."

She said the officer she spoke to told her it was her choice but recommended she go to the hospital to get checked out.

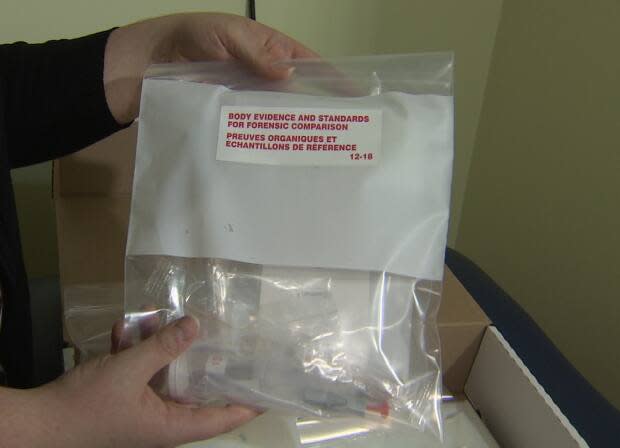

He also advised she could get a sexual assault kit performed to collect any evidence in case she decided she wanted to pursue charges against the man.

"The police officer had told me that I shouldn't have to wait long. Like, the words he used were that, 'they would treat this as seriously as if you had a gunshot wound.'"

She took a number in the Chalmers emergency waiting room, surrounded by men, and anxiously waited. A nurse eventually brought her into the triage area and began asking her some routine questions.

"I just kind of interrupted her and said, like, 'I'm here for a rape kit.'"

The nurse then took her to a quiet room with a door, where she could be alone, while they contacted a nurse trained to do the sexual assault kit.

After roughly 15 to 20 minutes, they put her on the phone with a representative of SANE, the sexual assault nurse examiner program, who told her she was "very brave" for coming in and then, "very matter of fact," told her no one was on call that night.

No one was on call until the following evening at 8 p.m., the SANE representative said, but she was willing to conduct the exam herself in the morning.

"Knowing that there could have been help available, and they just — there was no one around — was hard to hear," the woman recalled.

"And I was kind of in shock that I was making an appointment to see someone for this trauma."

It was a very vulnerable thing to have to walk in and explain what had happened and ask for help. And so to be told that I had to come back tomorrow … it didn't help the situation. - Alleged sexual assault victim

She says she realizes nurses are short-staffed, but doesn't agree with offering the SANE program "only sometimes."

"It was a very vulnerable thing to have to walk in and explain what had happened and ask for help," she said. "And so to be told that I had to come back tomorrow … it didn't help the situation. I was already in like a rough spot.

"I just really wanted to have it feel like it was over with. And being asked to wait until tomorrow was like asking me to keep sitting with that experience for 12 more hours, as if it was like a cold that I could deal with tomorrow."

She was also surprised the hospital didn't offer for her to stay, she said.

She called police again shortly after 1 a.m., from her car in the parking lot.

"When I'd spoken to the police [the first time], they had told me that this was a big deal and that it would be treated as such and that I would get the medical attention that I needed."

She spoke to the same officer, whom she says was "very surprised" to hear she was sent home without any care. He said, "That shouldn't have happened to you," she said.

His partner was also surprised, so much so he drove straight to the hospital to meet with her and then talk to the nurses.

He told her if no one was available at Chalmers that night, then they might have to drive to Oromocto or Woodstock. "But he's like, 'We're going to find a place for you to be seen tonight.'"

No one at Chalmers had mentioned another location was an option, she said.

After about 30 minutes, the officer came out to tell her Chalmers had called in a nurse and she would arrive shortly.

"I'm very thankful that the police were able to find someone … to help me that night."

Felt like an inconvenience

At the same time, she felt even more awkward, as if she were an inconvenience to the nurse because this happened to her.

"When she first came out, all she said was that like, 'Well, I got the call. Everyone got a call. Don't worry.' So it was just this idea of like, 'Everyone's up now, you've got the help you needed, don't worry,' kind of thing. As if I had made this a big deal.

"Whereas I was told that what happened to me was a big deal. So I didn't like that I had to make it a big deal to be taken care of."

The nurse swabbed her mouth and under her fingernails for DNA, then had her strip down on a piece of paper to catch any hairs, fibres, or other evidence. Then she used a black light to check her body for any residue.

Although the nurse had explained the procedure at the beginning and told her she could stop at any point, the woman says she wishes she had been asked about each step. "Like, 'I'm going to do this now, is this OK?'"

"I don't think anyone set the system up to make a situation like this worse. But if anyone I cared about had the same thing happen to them … I wouldn't want this to be how they're taken care of."

No one who has been sexually assaulted should have to fight to get someone to care, she said.

Horizon reviewing on-call staffing

In a news conference held Monday afternoon, Melanson said her thoughts were with the survivor, and commended her for her "bravery and strength" in coming forward with her story.

She said what happened to her is "unacceptable" and that Horizon is reviewing the processes and protocols for the SANE program, and working with partners to make sure patients receive timely, quality care.

"There will be follow-up undertaken with those working within this program, reinforcing the on-call scheduling as well as what are the contingency plans that are in place if there ever is any circumstance as what occurred on this particular night where there was an obvious gap in service," she said.

"There should be staffing that is available on a 24/7 basis." - Margaret Melanson, interim CEO and president, Horizon Health Network

Melanson said there are five trained sexual assault nurse examiners and one full-time equivalent SANE co-ordinator in the Fredericton area, and that at least one should be on staff and available at all times.

However, she said it appears staffing shortages led to there not being one available on the night in question.

As a result, Melanson said a nurse who'd recently ended her shift had to be called back to work to conduct the exam.

"There should be staffing that is available on a 24/7 basis," Melanson said. "That is how the program is designed — for someone to be called immediately to come in if someone is not already in the department to see a patient who presents with this type of distress."

Melanson also clarified a comment she made in an earlier email statement about how survivors could be expected to be asked to go home and return to the ER at a later time to have the exam done.

In her statement, Melanson said "it is within the standards of practice that if an in-person examination cannot be conducted immediately, a patient is then provided with the option of returning home, to a comfortable environment where supports may be in place, rather than waiting in the emergency department."

On Monday, Melanson said that while a sexual assault forensic test can be administered hours after the assault has taken place, no patient should be denied one when they present to a health-care facility requesting it.

"In terms of the acceptability of the retrieval of a specimen for individuals in this circumstance, waiting several hours does not contaminate that from occurring."

But, she said, asking a patient to wait for one, when they've gone to a hospital, is "unacceptable."

"And so our intention would be that we would certainly provide this service as efficiently and as quickly as possible and not necessitate someone to go home and then have to wait to come back in to have that examination completed."

Response within one hour: co-ordinator

Roxanne Paquette, co-ordinator of the SANE program for both Horizon and Vitalité, did not respond to a request for an interview.

Earlier this year, she told CBC there was a protocol that a SANE nurse respond within one hour of a call.

Horizon's SANE website says the program's objectives are to, "provide access to the care and specialized services of a SANE nurse in a reasonable time frame and appropriate geographic location."

The program is offered at 12 of the province's 23 hospitals — only those that are open around the clock. But the SANE nurses can travel to other hospitals, Paquette said.

About 80 nurses in New Brunswick have received special, trauma-informed training to treat survivors of sexual violence and administer sexual assault evidence kits, she said.

That's a good number for the province, Paquette said, though she added she'd love to see more.

Lorraine Whalley, executive director of Sexual Violence New Brunswick, said having trained staff available across the province to see someone immediately is what's needed.

Best practice, she said, in terms of evidence-gathering, receiving treatment and trauma-informed care is "the sooner, the better."

And it can potentially be retraumatizing for victims to have to wait, said Whalley.

"We're certainly all aware of the challenges that our health-care system is facing," Whalley said. "Our understanding though with the work that we've done with the sexual assault nurse examiner programs across the province is that when somebody who has been sexually assaulted presents in an emergency room, they are prioritized.

Happened to someone 'already traumatized'

"They are triaged, you know, at the top level, practically, and procedures and protocols have been put in place so that they don't have to wait. So it's unfortunate that … someone who has already been traumatized in that way has to wait, or is told to wait, and then has to advocate for herself or themself to receive treatment, or to be seen."

Fredericton Police Force spokesperson Sonya Gilks confirmed the force received a call "of the nature" described, "and that an officer provided assistance and followed up with the Chalmers hospital on behalf of an individual who had reported a serious sexually based crime."

"The file is now with the RCMP," for jurisdictional reasons, Gilks said.

New Brunswick RCMP spokesperson Cpl. Hans Ouellette said the force couldn't confirm or comment on whether an individual is the subject of an investigation.