Reverend James Lawson, civil rights activist and nonviolent protest pioneer dies at 95

NASHVILLE, Tenn. — James Lawson, the man who inspired a generation of nonviolent activists in the earliest days of the Civil Rights Movement and helped organize the push to desegregate lunch counters in Tennessee, died on Sunday. He was 95.

Minister, professor, activist, and descendant of enslaved family members, Lawson lived peacefully in the middle of much turmoil. The Rev. Christian Washington of the Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles, where Lawson pastored from 1977 to 1999 and later served as pastor emeritus, confirmed his death to The Nashville Tennessean, part of the USA TODAY Network, on Monday.

Imprisoned as a conscientious objector during the Korean War in the early 1950s, Lawson was also kicked out of Vanderbilt University and arrested for organizing student demonstrations. During his incarceration, he said he learned about the nonviolent protests led by Mohandas Gandhi in India.

In-depth: Civil rights advocate James Lawson was rooted in faith

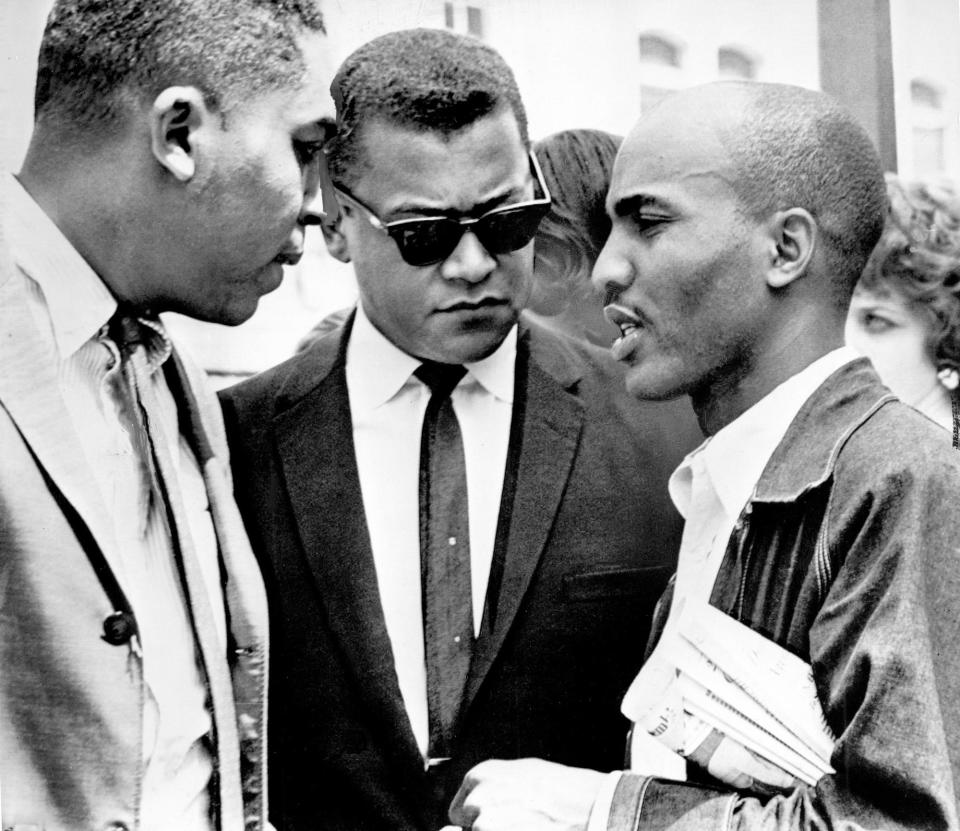

Lawson was an American civil rights icon who worked alongside luminaries like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Diane Nash, John Lewis, and C.T. Vivian to promote nonviolent activism in the early 1960s.

Shortly after Lawson and King first met, King encouraged Lawson to travel South to have a greater impact on the Civil Rights Movement. Lawson transferred to Vanderbilt University, where he was one of just a few Black students.

In 1959, Lawson began leading workshops in nonviolence for young Black students from local Nashville colleges. Among his pupils were students who would soon rise to prominence across the U.S. — Lewis, Nash, Bernard Lafayette, and others.

The lessons were both philosophical and physical in scope, with Lawson teaching the gathered activists both the principles and practicalities of resisting violent oppression without lashing out.

Some were initially skeptical of the tactics, considered radical at the time, though they've now become synonymous with the Civil Rights Movement. In a 1985 interview, Nash recalled Lawson putting students through intensive role plays, where they would practice sitting at a pretend lunch counter and protecting their heads from a severe beating.

They would practice not striking back when they were hit, or putting their bodies between an assailant and a fellow protestor.

"There were many things that I learned in those workshops, that I not only was able to put into practice at the time that we were demonstrating and so forth, but that I have used for the rest of my life, that have been invaluable in shaping the kind of person I've become," Nash said in the 1985 documentary.

Nash and the others would soon put Lawson's lessons into practice, organizing lunch counter sit-ins in Nashville. As the movement progressed in Nashville, Vanderbilt expelled Lawson in 1960 for his role.

In 1960, Lawson drafted the first purpose statement for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, an organization led by Nashville students that would dramatically alter the landscape of the movement in the years to come. When SNCC members took up the mantle of the Freedom Rides in 1961, Lawson was arrested and held in a Mississippi prison for weeks.

Lawson was working on the sanitation strike in Memphis in 1968 and called King to participate.

Lawson was then one of the leaders of the silent march to honor King in Memphis after he was assassinated.

'People should be treated equally and justly'

Lawson told The Tennessean in 2013 he felt Jesus’ call to do something.

“The politics of Jesus and the politics of God are that people should be fed, that people have access to life, that people should be treated equally and justly,” Lawson said. “Especially the marginalized. The poor, the illiterate, the jailed, the hungry, the naked — those are all terms Jesus uses. The alien, the stranger, the foreigner, you’re supposed to treat them as you do yourself.”

He looked to the gospel account of Mark, the story of Jesus healing a demon-possessed man. When the city’s residents saw the man was better, they were terrified.

“When all kinds of people in the United States become human, the people who have been mistreating them as less than human then are fearful,” Lawson said. “That’s the issue of racism in the United States, sexism in the United States, violence in the United States."

He was the son of a minister and raised among 10 brothers and sisters in Massillon, Ohio.

When he was younger, Lawson would punch people who called him racist names. But then he told his mother, Philane Lawson, what he had done.

“What good did that do, Jimmy?” she asked.

That simple question helped set her son on a new path. “I made decisions that changed my life forever and basically directed me toward nonviolence,” Lawson said.

Lawson coached a movement

From Nashville to Memphis and beyond, residents honored Lawson's legacy and pointed to the progress he helped foster, even while noting the work yet to be done.

"The world has lost an irreplaceably powerful leader in the fight for social justice," Metro Nashville Council member Joy Styles said. "We owe Rev. Lawson a debt of gratitude for how he led change for the world that we live in."

Metro Nashville At-Large Council Member Zulfat Suara said he was a "testament of the struggle for African-Americans in this country and a reminder of all the work, still to be done."

House Minority Leader Karen Camper, D-Memphis, said his life was intertwined with some of the "most important moments in Tennessee history, and his level of commitment never wavered over his lifetime."

"And yet, he always remained humble and gracious," Camper said.

For Nashville native Howard Gentry — longtime elected official and the city’s only Black vice mayor — Lawson humanized and personified nonviolent protest.

“I was an angry Black kid for the way I was mistreated; when I was a teenager, segregation was still rampant,” Gentry, 72, said. “I played football and I loved to hit. But to hear Jim Lawson say to not fight fire with fire? He was not a soft person. He was a tough guy. But in his toughness, he would tell you not to fight back and to love and to meet violence with nonviolence.

“It took more courage for people like Jim Lawson to be nonviolent than it did to fight,” he said.

Historian David Ewing said Lawson changed history nationwide.

“Lawson taught students like John Lewis and Diane Nash nonviolent responses. The reason the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins were so successful was because they were peaceful,” Ewing said.

“Lawson was the coach of the lunch counter sit-ins. He mentored the students, came up with strategy and later cheered everyone on like John Lewis and Diane Nash.”

Ewing said Lawson came to study at Vanderbilt University’s divinity school at the urging of King. Lawson was the divinity school’s first Black student accepted, until he got expelled for helping with lunch counter protests.

Vanderbilt University began to make that right in 2006 when then-university president Gordon Gee brought Lawson back as a divinity school professor, Ewing said. About three years ago, the university also purchased Lawson’s writings and photographs.

In 2021, Vanderbilt launched the James Lawson Institute for the Research and Study of Nonviolent Movements.

In Nashville most recently, Lawson's name was given to a Bellevue high school in 2023. The $124 million facility has 1,600 students and 150 staff and faculty.

In January of 2024, the city of Los Angeles dedicated a one-mile stretch of Adams Boulevard in his honor in front of the church where he served as pastor emeritus.

“Up until a few months ago he was still doing nonviolent protest seminars, well into his 90s,” Washington of Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles said Monday.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: James Lawson civil rights activist and nonviolent protester dies at 95