Swastika Mountain's new name set to honour Indigenous leader instead of evoking Nazi history

When two 19-year-old hikers disappeared on Swastika Mountain earlier this year, a modest butte in a remote part of Oregon ended up rising to prominence due to its offensive name.

After their disappearance, the Oregon Geographic Names Board received three requests to change the name of the 1,219-metre-high (4,000-foot) peak found south of Eugene, Ore., to something not associated with Germany's Nazi Party.

"When Oregonians found out that there was a Swastika Mountain in their state, a lot of people didn't know that the name even existed," said Bruce Fisher, president of the board.

"It's sort of in the middle of nowhere."

Fisher said the board often deals with requests from the public to change names if they are considered out of date or offensive.

In this case, the board whittled down the ideas to one, and it's expected to make a final decision in December to approve naming the mountain after an Indigenous chief. The other two proposals were withdrawn.

Fisher reached out to David Lewis, an Oregon State University Native studies professor and Grand Ronde tribal member, who suggested a name to honour Chief (Halo) Halito, a Yoncalla Kalapuya tribal leader of a community that lived on the Row River in the 1800s.

Mount Halo could be the mountain's new name as early as 2023, if the plan is also approved by higher authorities and tribal councils.

2 lost teens drew attention to mountain

The unassuming peak first ended up on the media's radar in January.

That's when two Oregon teens — Christian Farnsworth and Parker Jasmer — who spent nine days missing in deep drifts were found after they dug an SOS into the snow.

After the pair were airlifted out of the Umpqua National Forest, people were left wondering how an Oregon land feature got the name of a Nazi symbol.

Fisher, a mapping expert, said the origin of the moniker is muddy.

"We don't really know, but we do know it started appearing on maps. The 1935 USGS map has the name — Swastika Mountain," he said, referring to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Fisher found out that there was a U.S. post office with the same name, as well as a bid to start a town nearby, between about 1909 and 1912. But the post office closed.

"The name swastika came from a cattle brand that is being used in the area, but ... that post office closed. There's no real historical tract to follow to how this mountain in Lane County got its name."

Swastika has had different meanings

It's believed a cattle rancher in the area named Clayton Burton branded his stock with a swastika — decades before Nazi Germany's use of the symbol, which led to it being equated with fascism and hate.

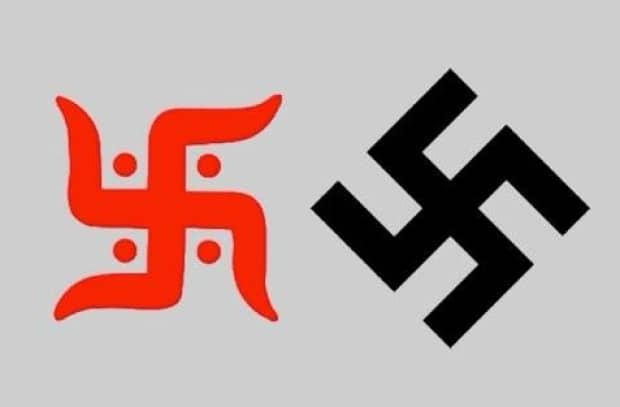

Before the Second World War, the swastika symbol had different connotations — some even associated it with good luck.

In the ancient Indian language of Sanskrit, swastika means "well-being."

At one point in the 1930s, swastikas were used to market everything from fruit and beer to Coca-Cola, and the symbol was found in Boy Scouts' material, according to U.S. graphic design writer Steven Heller, whose book The Swastika and Symbols of Hate was published in 2019.

But whatever significance the swastika symbol had when the Lane County Peak became known as Swastika Mountain, it had no real ties to the land's history.

In the search for a new name, Fisher said, the country's largest naming board has been looking for something meaningful.

"We want some identity here — some historical identity. This will be a new permanent name," he said.

Indigenous people 'excited' about names

The butte in question is the traditional territory of the Yoncalla, who lived near Fort Umpqua, where they encountered settlers in the 1800s — from explorers to Hudson's Bay Company fur trappers, said anthropologist David Lewis, who has spent years studying Oregon's history and is a descendant of the Santiam, Takelma and Chinook tribes.

Oregon historical writings speak of how in the 19th century, there was a vibrant Kalapuya village where Chief (Halo) Halito lived on the nearby Row River in a community of about 100 tribal members.

In his research, Lewis describes how the Yoncalla chiefs signed a treaty with the Umpqua and Kalapuya First Nations and the U.S. government on Nov. 29, 1854.

Within two years, the government began moving tribes inland, away from their lands to the Grande Ronde reservation — but Chief Halito refused, saying: "I will not go to a strange land," said Lewis, who has researched the writings of the chief's longtime friend and American pioneer Jesse Applegate.

"Native people are excited about bringing these names back to the landscape. It kind of bring us back into focus," Lewis said.

Chief Halito remained in his traditional territory with the support of the Applegate family, who were prominent, he said.

"He stuck by his feelings, and he and his family were able to stay in their land."