'Teleholic' essayist Elissa Bassist's new memoir Hysterical explores screen culture through a feminist lens

Elissa Bassist is not an actor, though she has played one on TV. "I'm a teleholic," the essayist, humor writer, and editor of the "Funny Women" column on The Rumpus tells EW. "And I grew up sprayed in the retinas by the male gaze — where women onscreen are fallen in love with reluctantly or gagged briefly or suffer from head trauma or are otherwise not wearing pants or speaking in complete sentences — [so] I become a woman created in its image. Which I didn't know until I went behind the scenes as a background actor and saw sexism live."

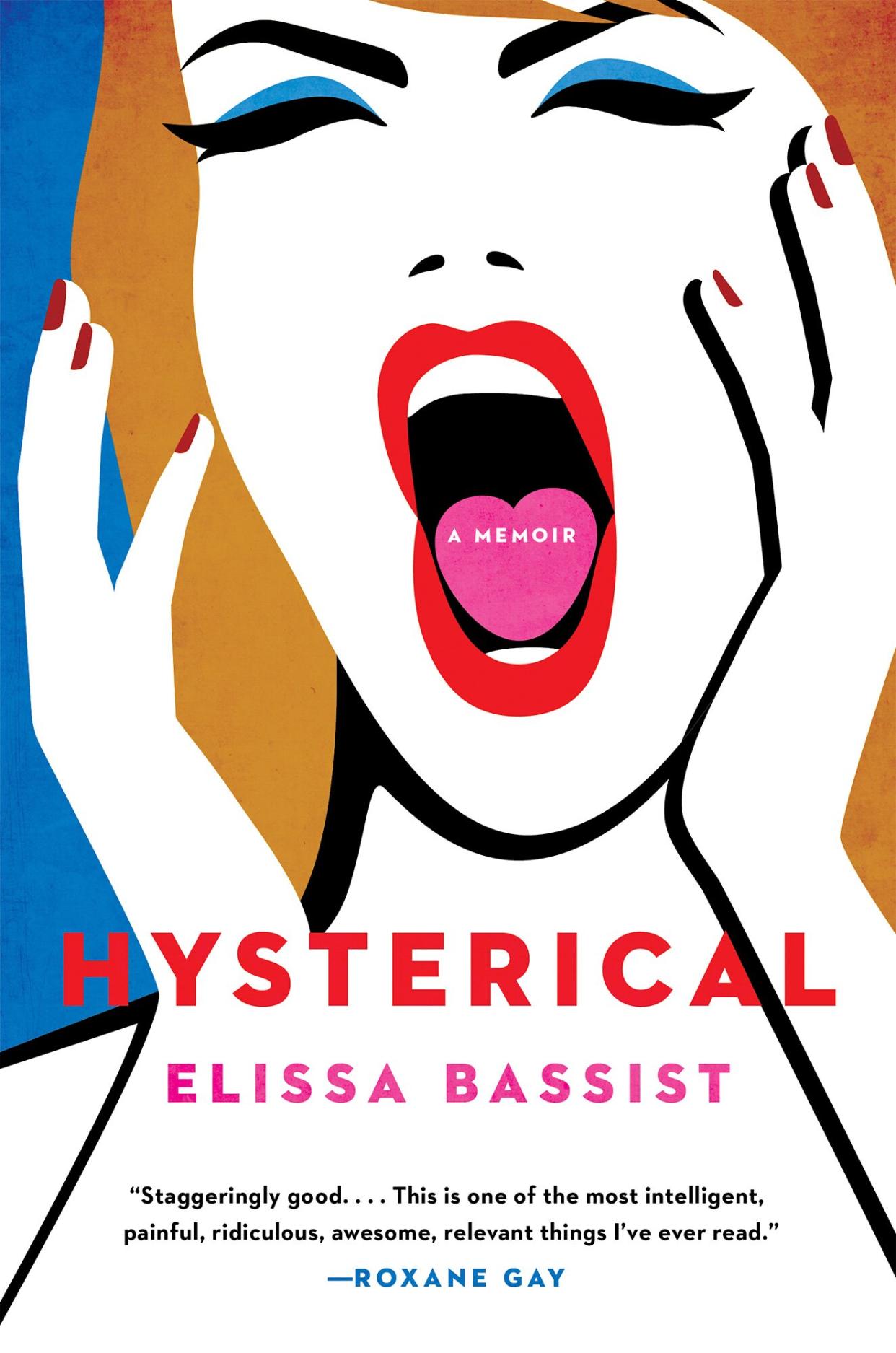

Below, Bassist — whose memoir debut, Hysterical, out Sept. 13, has already earned high praise from Roxane Gay, Cheryl Strayed, and Transparent creator Joey Soloway — explores the perils of screen culture through a lens of modern feminism, and how background gigs on shows like 30 Rock put her on the same side of the screen as the characters "I fixated on, identified with, projected onto, and later imitated, deliberately or not."

Read on for an exclusive excerpt.

Hachette

Must-See Dead-Girl TV

How saps feel about love, I've felt about the television. And I felt about love how the unplugged must've felt about television, that it's a profound time-suck, energy waster, and indoctrinator. Will Joey Potter/Felicity Porter lose her virginity to Dawson or Pacey/Ben or Noel? was more important to me growing up than anything, more than my own virginity or thinking of TV as a mass medium of pedagogical socialization or communal hypnosis.

Joan Didion famously admitted she didn't want to be a writer. "I wanted to be an actress. I didn't realize it's the same impulse. It's make-believe. It's performance. The only diff erence being that a writer can do it alone."

I was as thirsty for fame as any millennial and thought I might want to be an actress also.

First I starred in 30 Rock, in season seven, episode eight, "My Whole Life Is Thunder," when Liz Lemon, played by the show's creator Tina Fey, is being honored as one of "80 Under 80" in media, and I played "the Usher." I handed Lemon and her plus-one, Jenna Maroney, event programs as they walked in; then I stood in the back of the ballroom the whole time. In a deleted scene, as Jenna runs out of the room after a change in lighting reveals that she is old, I throw the programs in the air as I dive out of her way, improvisationally. The fifteen hours of filming were perfect; I had no notes and no lines, and earned $115 and two meals.

Next I was in the 2012 "metamodern film" The Comedy, starring male actor Tim Heidecker from Tim and Eric and costarring male actor Eric Wareheim from Tim and Eric. I played "Hipster Girl" and wore my own clothes and was in the movie's party scene, where the characters and the stars who played them were blitzed on alcohol and party drugs.

The experiences, like the sets, were antithetical. (The TV set was in Queens, inside a schmaltzy event arena that looked like a discotheque inside of a chandelier museum from the point of view of a Sears portrait studio. The film set was a warehouse party inside a real Brooklyn person's apartment loft ). In The Comedy, the male director told the hipster girls and hipster boys to dance even though there was no music (it's added in postproduction) and to appear as if we were talking. "Mime talking, mime listening, mime understanding," we were told as we swayed and twerked to the music in our minds and fake-laughed at each other's nonverbal jokes and spoke only body language.

The TV show was created by a woman, directed by a woman, co-written by a woman, and starred women, and the film was directed by a man, co-written by three men, and starred so many men. The latter is the usual. In TV, film, and digital programs, women have comprised less than one-third of creators, directors, writers, executive producers, editors, and cinematographers, while tons of shows have employed no women whatsoever. On the top two hundred fifty grossing films in the past twenty-four years, less than a quarter of all directors, writers, producers, executive producers, editors, and cinematographers have been women. And although people from underrepresented groups make up 42.2 percent of the US population, they have been virtually nonexistent as creators, directors, writers, and executives.

Since cave art, men have been the primary legislators of narrative, the guardians of meaning, and the executors of what we see and hear.As a teleholic I saw with male eyes, heard with male ears, felt through male touch, discerned through the male point of view, and I used male language — so most of what I understood about myself, my body, history, and the future came from a man's mind, and my own senses lost their authority.

Mindy Tucker

Man created, directed, and edited woman in His own ideal image of her. Every day I switched on the television to keep me warm, and I watched men be heroes and women be — well, what? Depended on the men.

Women had a few deadend roles: ingénue, object that appeared smaller than it was, sex doll with a heartbeat and a mouth that was just for show, and wife and mother (women perform the miracle of birth half a dozen times if they are any good at womanhood). Whatever her role, a woman served as a funsize looking glass for a man that reflected him double his actual size (women also paraphrased Virginia Woolf).

If or when they talked, women had one conversation only: "Men, men men men men — men men men. Men? Men men: men men men men men. . . men. Men men men men men men, men, men! (Men men men men men.) Men — "

Judging from the screen, it seemed that white women accounted for less than 33 percent of the US population and that there were five or so Black women and women of color and LGBTQIA+ people on the planet.

White men, ubiquitous, ran the world, and they objectified women for sport.

Unlike a man, a woman objectified herself, since appearance was her primary concern and purpose on earth.

If a woman onscreen was not a spouse or a sidepiece who had forgotten her own personality while volunteering to be a man's soul for him, then her singlelady days were meaningless and cursed, especially on national holidays. (If she said otherwise, she was lying.) A childless woman was purposeless and unhappy, and her choices sparked public debate over why in Gd's name she disrespected the American flag like that.

On any heroine's résumé her special skills were: passive, helpless, decorative, ethereal, receptive, and affected by uncontrolled extreme emotion. "Chores" filled "previous experience," since a heroine had servitude in her heart and couldn't handle a conversation or anything more than a broom, a baby, or men's every desire.

And as I saw on TV and on the set of The Comedy, the male gaze and ear have a type. Women ranged from blindingly beautiful to secretly beautiful, from thin to skinny, from white to tan. Women stayed girls and sinned by growing up. Women were 8s or above out of 10, and any woman below an 8 should kindly drown herself. And women were freezing since they weren't allowed pants.

Even in my rotation of femaleled, femalecentered, femalefocused shows, heroines were given voice, life, and lowcut tank tops by men who have never heard a woman's thoughts. All the women — however strong, however leading — were hot, tiny, youthful, feminine, next to naked, and the badass ones were a lot like men in women's bodies.

I took the screen as Truth. I was supposed to. I was supposed to according to cultivation theory, which says the more hours we spend/waste "living" in the television or screen world, the more likely TV calls dibs on our thoughts and shapes them, stretches them out, and the fine lines between life/art, corn syrup/blood, her/me become so fine to us we lose them.

I saw myself in the characters I fixated on, identified with, projected onto, and later imitated, deliberately or not. And since men devise and immortalize certain stories, they boss us into their version of how things go, so the narrowest and eeriest interpretations and imitations emerge. Watching anything, I'd look up at the screen and then look down. Not a temple. Even as I zoned out, my ego kicked in, and I'd see two things at once: the scene in front of me and myself in it. As if I was there and Angel kissing Buffy landed on my tongue. Or more as if I wanted to be Buffy, a vampire slayer who loses her virginity to a man who becomes a monster. Or even more as if I'd scan Buffy's body for imperfections where I had imperfections — upper arms, stomach, thighs, calves, ankles; cellulite, stretch marks, pale skin, acne — and in this way, I believed, I'd know myself, by how I compared and judged myself. This is the serrated edge of the feedback loop. My screen surrogates were sexy and perfect, and freaks in the sheets and ladies on the streets, so it was dire for me to be sexy-perfect-freak-lady. Because girls who grow up sprayed in the retinas by the male gaze become women created in its image. Because the reality of the white male gaze and ear is our reality.

Excerpted from Hysterical: A Memoir by Elissa Bassist. Copyright © 2022. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Related content: