How Truman Capote’s Esquire Stories Ruined His Life

In the mid-’50s, Norman Mailer described Truman Capote as “a ballsy little guy,” yet also “the most perfect writer of my generation, he writes the best sentences, word for word, rhythm for rhythm.” Mailer added, “he has less to say than any good writer I know,” due to his “attractions to Society.”

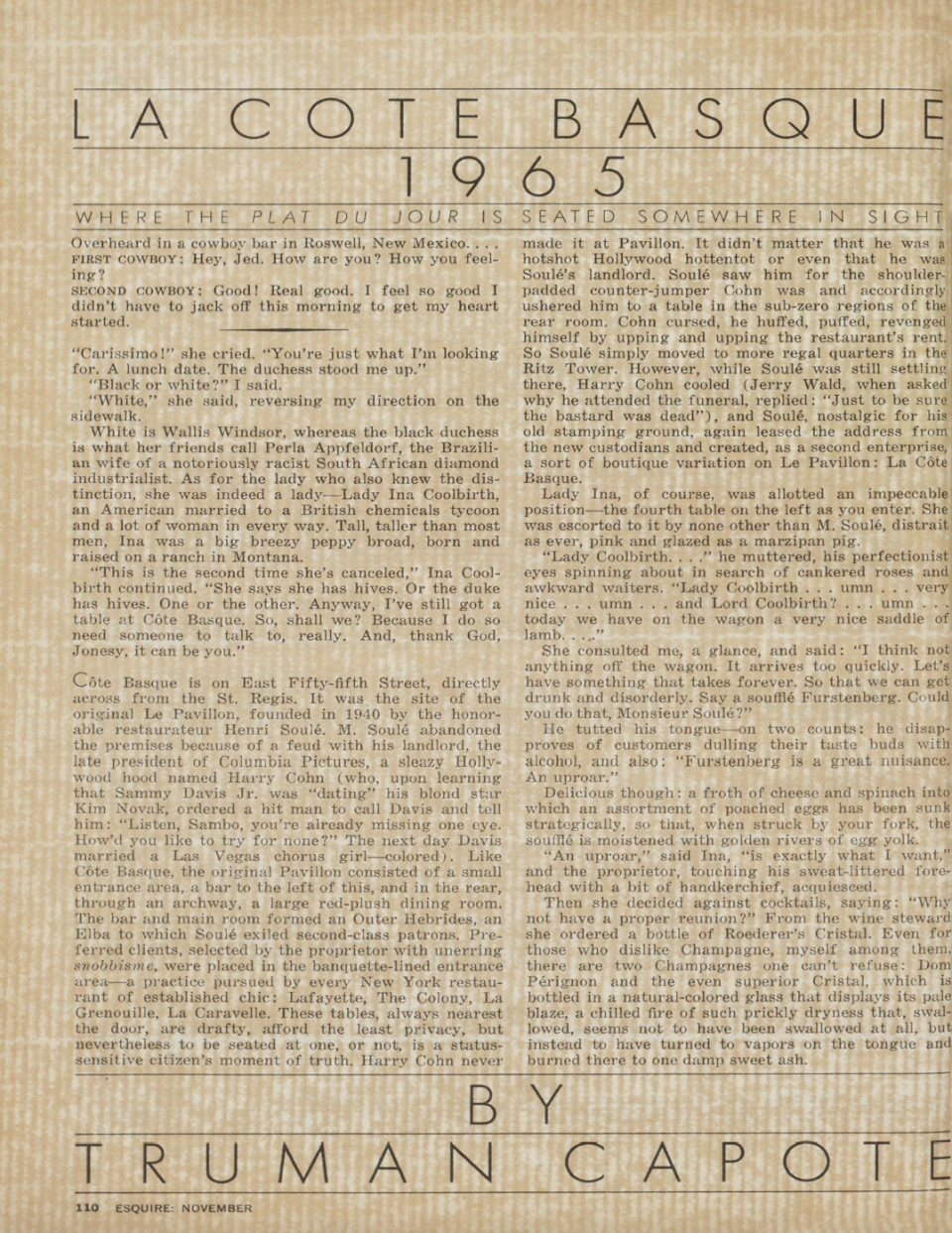

It comes as no surprise that Ryan Murphy, who is drawn to the sordid complexities underneath polished, shiny surfaces, chose to explore the public coming-apart of one of the last great literary celebrities. In Feud: Capote vs. the Swans, which debuted its first two episodes on FX this Wednesday night (streaming on Hulu), he takes on the Esquire story that ruined Capote’s standing with his society friends. The series doesn’t traffic in camp; its reference is closer to Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard rather than Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard. Its concern, outside of Capote’s central act of betrayal—he aired his friends’ dirty laundry in the second published chapter, “La Côte Basque, 1965,” and quickly found himself cut-off by his dearest pal, Babe Paley, wife of CBS founder and chairman William S. Paley—is that of vanishing worlds.

It’s all of a piece. There’s the high-society world of Paley (Naomi Watts), Lee Radziwill (Calista Flockhart), and Nancy “Slim” Keith (Diane Lane), and the other women Capote (Tom Hollander) dubbed his Swans. It’s an insular world of manners, etiquette and discretion that seemed antiquated in the celebrity-crazed 1970s, during which the majority of the series is set. For all their immaculate—sometimes acquisitive—taste, intelligence, and power, there is a lingering awareness that their time had come and gone.

“They grew up in the ’20s, by the ’30s, they were married,” Gus Van Sant, who directed six of the eight episodes, tells me. “They really were products of that world which was really crashing by the ’60s. It’s almost like the 1800s is crashing. By the ’70s, you have much more free-wheeling society events like Studio 54, which had nothing to do with the hierarchy of museum dinners.”

The can’t-look-away quality, though, is about how Capote sold his friends out. “I don’t think Truman gave a shit,” his friend, Dotson Rader, who was a regular Esquire contributor at the time, told me last week. “Truman was a writer and he was also a journalist. I’ve done a lot of stories and one of the things you do when you’re on a story on someone that is self-protective, you appear to be their friend. That’s the role you play as a journalist, so a lot of them get pissed off when you write critical stuff. But that’s your job.”

It’s a juicy story—one in which Esquire played a major role. There are not a lot of Esquire staffers still around from that time, but we’ve tracked down those who are to get the skinny on how it all went down.

The Legend of “The Tiny Terror”

Aside from Ernest Hemingway, Capote was the 20th Century’s most recognizable American writer to the person on the street. The height of Capote’s fame came in 1966: In Cold Blood was a runaway bestseller and Capote hosted the Black-and-White Ball at the Plaza Hotel in New York. Rader called it “the single greatest act of non-literary self-promotion by any writer in history.” Capote preened; the event wasn’t the ball itself but who’d been invited, and more importantly, who had not.

Capote had never been a regular Esquire contributor, though his 1958 novella, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, his most famous work of fiction, appeared in the magazine. Originally intended for Harper’s Bazaar and dropped after a change in management—the new editors found the piece too risqué—it serendipitously landed in Esquire’s lap. Capote published a few small pieces after that, including an ode to the poet Ezra Pound with an accompanying portrait by Richard Avedon. Esquire devoted an entire issue to the Black-and-White Ball, as well as dueling profiles of the author upon the publication of In Cold Blood: one praised him and the other called bullshit. As Wyatt Cooper, Anderson’s father, once said of Capote, “He improves on the poverty of God’s own imagination.”

Why then, did Capote’s Answered Prayers wind up in Esquire and not The New Yorker? Rader later told George Plimpton: “Truman at that point was very worried about the aging of his audience and he wanted to be in a magazine that had a younger readership. I said, ‘Do you know demographically the occupation of the greatest number of New Yorker subscribers?’ He said, ‘No,’ and I said, ‘Well, if you break their audience down by occupation, the leading subscribers are dentists. That’s your audience—people with toothaches waiting for the drill.’”

“We knew that The New Yorker had turned it down,” Esquire Publishing president at the time, Gilbert Chapman, tells me. “It was too controversial as I remember. Our corporate council didn’t want Esquire to run it either, but Don Erickson and I pleaded our case. I thought it would bring some attention to Esquire which it desperately needed in those days. Particularly from the advertisers.”

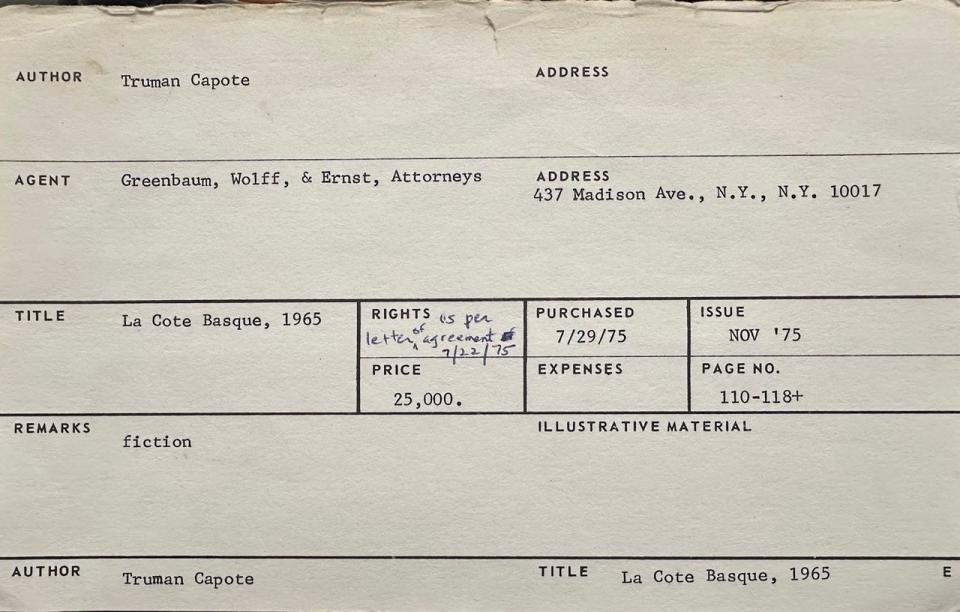

The money didn’t hurt. Esquire offered Capote $25,000 for “La Côte Basque, 1965,” the most money the magazine ever shelled out for a story to that point.

The Moment Shit Went Down

Capote felt the pressure of his own great expectations. He’d been talking about Answered Prayers since 1958, yet it only existed in his head. But when Esquire’s fiction editor, Gordon Lish—AKA “Captain Fiction”—approached Capote about contributing something to the magazine, Capote agreed. He hadn’t published anything of consequence since In Cold Blood when he wrote “Mojave” over several weeks of focused concentration in early 1975. Gripped with anxiety, he had Esquire editor Don Erickson fly down to Key West (where he’d been working) to read it in person. Capote sat by the pool, eyeing Erickson as the editor read the story.

After the piece received a glowing critical reception, Capote’s nervousness dissipated. To Esquire’s delight and surprise, Capote offered more. “We stood back on our heels in amazement that we were able to get from Truman Capote what other people hadn’t been able to get in such a very long time,” Lish told Capote’s biographer, Gerald Clarke.

Next came the bombshell that was “La Côte Basque, 1965.”

In the summer of 1975, Capote took Clarke to Gloria Vanderbilt and Wyatt Cooper’s Long Island home to swim—while the couple vacationed in Europe. Capote floated on an air mattress in the pool (heated to 90 degrees, during an energy crisis), while his friend read. Clarke deciphered some of the real-life events behind the fiction and Capote filled him in on the rest. Clarke warned Capote that his friends would not be happy about the story. “Naaaah, they’re too dumb,” Capote said. “They won’t know who they are.”

Did he ever get that wrong—as the reaction from some of the Swans was immediate and resolute. Even Capote’s writer friends, such as Kurt Vonnegut and Norman Mailer, were taken aback. “I would never have thought that he’d be so incautious—not even bold, but rash,” said Mailer. “I’d seen him being bold—he’d been bold all his life, but not rash.” William Styron found it inexplicable. “Writers don’t have to destroy their friendships with people in order to write. It seemed to me an act of willful destruction.”

However, nobody at Esquire knew what they were dealing with.

“I took no interest in ‘La Côte Basque’ inasmuch as it was at such a variance from the fiction I ran,” Lish tells me, “but it would be difficult not to have been aware of the expectation the entry aroused. I was fond of Truman, much enjoyed making too much vodka disappear in his presence but was thoroughly opposed to his Answered Prayers hullabaloo. I was completely indifferent to the identities, actual or rumored, of those persons exhibited in the piece. Indeed, I did not read the piece before or after publication.”

“We had absolutely no clue that the piece would cause a fuss,” editor Lee Eisenberg said recently via email, “not until Liz Smith broke the story in New York Magazine. It didn’t come from our publicity folks who, to be frank, didn’t know Babe Paley from Babe the Blue Ox.”

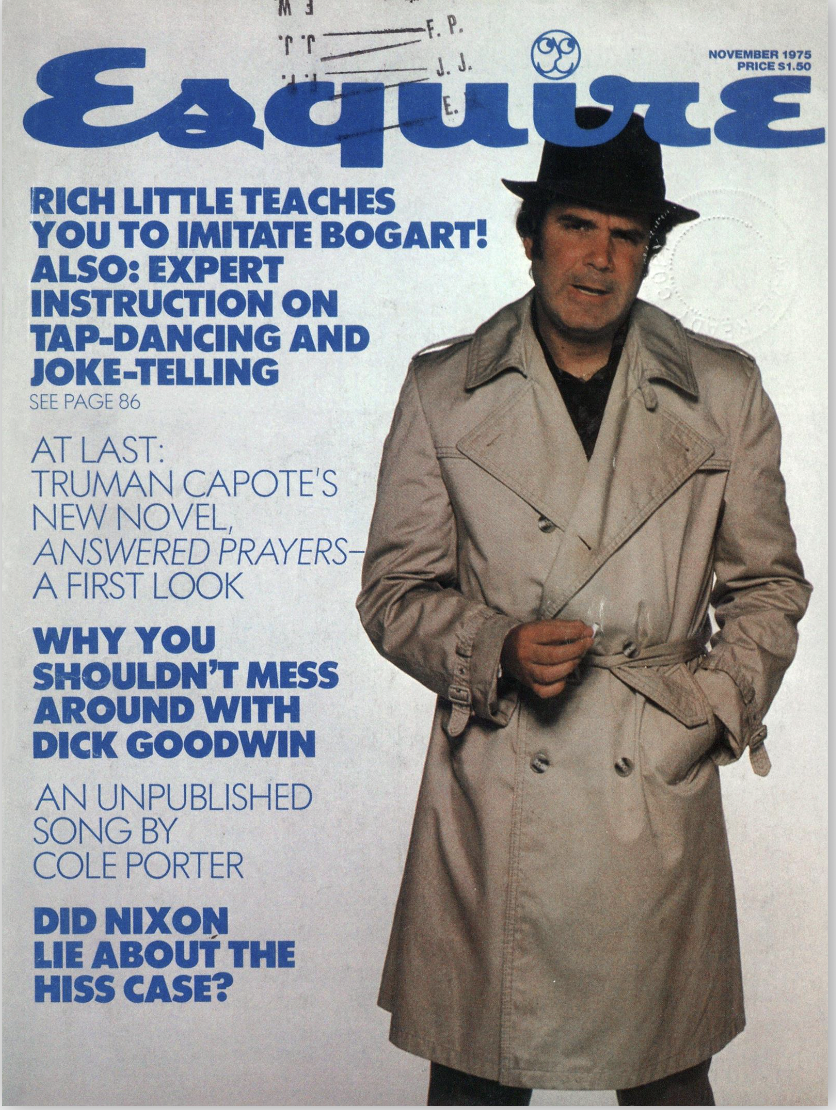

“La Côte Basque, 1965” appeared in the November 1975 issue of Esquire—on sale in early October—but the magazine’s editors didn’t fully appreciate the magnitude of the piece until Smith laid out the details of who-was-who in this roman à clef in the February 9, 1976 edition of New York (it’s fascinating today to think how long a shelf life a scandal could have).

The November 1975 issue was the only edition of Esquire that completely sold out, which is unheard of. Chapman tells me, “Somebody very smart at Esquire—and it wasn’t me—made a deal with union news to not destroy the returned copies from the newsstand as was customary but to send them back to Esquire. People were coming to the office, asking for copies. I was delighted for what it did for the magazine. For a time, I don’t know how long, subscriptions went up, newsstand sales went up. It was a big boost.”

The Court Jester Exits Stage Left

Babe Paley, who died in 1978 of lung cancer, never forgave Capote.

“He had built up this incredible edifice of social connections and great success and it crumbled overnight,” novelist John Knowles recalled. “The problem was that he had no stature, socially speaking. He had no family. He was only an ornament. There was nothing for him to fall back on. You could drop Truman Capote overnight because you weren’t going to alienate anybody. Truman was just all by himself out there.”

If Capote reeled from the shunning by Paley and Slim Keith, he exalted in the notoriety the piece created. And Esquire, without shame, took advantage. When the next installment, “Unspoiled Monsters,” appeared in the May 1976 issue, Capote donned the cover dressed in black, wielding a knife. He still had dirt to dish—though this time his targets were literary figures such as Katharine Anne Porter and Tennessee Williams—and it landed without the drama or personal consequences of the previous installment.

Still, you have to ask, why did the Swans trust him in the first place? This was the man who wrote, “The Duke in His Domain,” the 1958 New Yorker profile of Marlon Brando, a brilliant, acidic dismantling of the acting icon. “What did those silly women expect a writer was going to do?” said C.Z. Guest (Chloë Sevigny), one of the Swans who remained loyal to Capote. “Of course he was going to use the material sooner or later…But then I never told Truman anything of any importance.”

“People like to tell themselves they’re special,” Feud screenwriter Jon Robin Baitz tells me. “Maria Agnelli and Gloria Guinness”—two of the Swans that are not major characters in the FX series—“both said you guys are nuts, can’t you see what this is, can’t you see what he does, can’t you see who he is? I’ve talked to many people who didn’t trust him. Mike Nichols once said to me that Truman was the only person he ever met that lied about people just to hurt them.”

Capote’s final decade (he died in 1984 at the age of 59), saw him, more often than not, in rough shape, addiction to painkillers, vodka, and lousy lovers. He did enjoy lucid stretches, including in the late ’70s when he wrote the short story collection, Music for Chameleons. He replaced the Swans with Hollywood friends such as Joanne Carson (Molly Ringwald) and the wives of Billy Wilder, Jack Lemmon, and Walter Matthau.

“The ‘Côte Basque’ story didn’t destroy him,” Carol Matthau told Plimpton. “For him to be the court jester to the people of the moment, or those who are rich or have enough heritage or background, so they don’t need to be rich, well, that’s a joke. He knew better than that. A writer is another person behind the typewriter. Babe Paley’s not Babe when Truman’s behind the typewriter. He would have written the pieces even if he’d known what the repercussions would be. He had more balls than anyone.”

So, after all the hype, what about Answered Prayers? Dotson Rader believes a manuscript existed. Some said there was one hidden away in a safe deposit box, or accidentally left behind in a limousine. After his death, Gerald Clarke, Capote’s lawyer, Alan Schwartz, and Joe Fox (his book editor at Random House), searched high and low for a manuscript and found bupkis. The book appeared posthumously; it enjoys a select group of admirers, but it was not the masterpiece Capote envisioned.

Truman Capote's Legacy

Why do we still care about Capote? He’s outlasted so many of his more decorated contemporaries (Saul Bellow, John Updike, and Gore Vidal) in the public consciousness. The glib answer, according to Baitz, is that we all love an Icarus story—someone who flies too close to the sun. After the crowning achievement of In Cold Blood came a “deluge of distraction leading to inebriation, disinhibition and disease.” It’s not just the loss of genius or talent, but of human spark. “A brilliant observer is reduced to a slightly mangled, lesser version of what he was,” says Baitz. “And it’s done in public for the public without regard to his own safety. He’s the patron saint of his own lost cause.”

In the end, Feud: Capote vs. the Swans is a cautionary tale. Are we the guardians of our own talent? Or of our well-being? Do we have a responsibility to take care of the people we profess to love? Capote and the Swans were unforgiving; they lived in a ruthless world, and all suffered because of it.

I’ll give the last word to Capote, who once said he’d like to “wake up one morning and feel that I was at last a grown-up person, emptied of resentment, vengeful thoughts, and other wasteful, childish emotions. To find myself, in other words, an adult.”

You Might Also Like