‘Twister’ Director Jan de Bont Never Heard of Sequel ‘Twisters’ Until Its Trailer Came Out and Pines for ‘Godzilla’ Movie He Never Got to Make

Released in May 1996, “Twister” assembled a creative team as formidable as the forces of nature that gave the film its name.

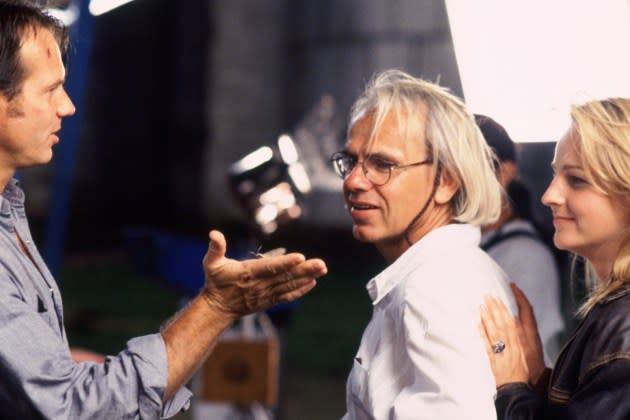

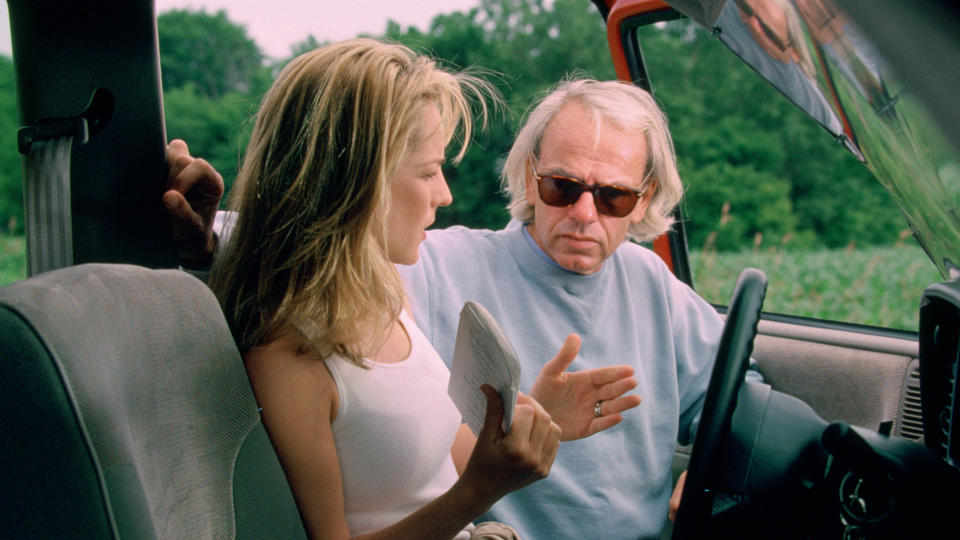

Co-written by “Jurassic Park” author Michael Crichton and his then-wife Anne-Marie Martin, produced by Kathleen Kennedy, executive produced by Steven Spielberg, Walter Parkes and Laurie MacDonald and directed by Jan de Bont, the $495 million-grossing blockbuster was poised for success before a frame of film was shot. But even with visual effects firm Industrial Light & Magic (coming off of three Oscar-winning benchmarks for “Terminator 2: Judgment Day,” “Jurassic” and “Forrest Gump”) providing what the MPA would describe as an “intense depiction of very bad weather,” de Bont recalls that actually telling a story involving tornadoes — you know, without everyone involved risking life and limb — proved to be an incredibly tough challenge.

More from Variety

“This was such complex new technology,” de Bont tells Variety. “We had 300 shots in the movie, and rendering would take 24 hours for every single shot.”

With the 4K release of “Twister” and ahead of the release of “Twisters,” a standalone sequel he says he had nothing to do with, de Bont recently spoke via Zoom about the arduous process of completing its 1996 predecessor. In addition to recounting how ILM’s proof-of-concept reel was so convincing that it ended up becoming part of the movie’s marketing — yet did not feature a tornado — he reflected on the personnel changes and real-life difficulties faced by the cast and crew while filming, explained what led to his step back from directing after the modest success of the 2003 sequel “Lara Croft: Tomb Raider — The Cradle of Life,” and hinted at the work he was sad not to complete after more than 50 years as a cinematographer and director.

Coming after “Jurassic Park,” did you get the sense that ILM was especially confident that they could pull off the technological challenges of “Twister?” Or even after making the proof of concept that they used for the film’s teaser trailer, was it still a scramble to pull it off?

It was a “hail Mary” because we made that famous shot with the tire coming [at the camera]. And that is partially visual effects, but it also had no tornado in it, so it showed things we kind of knew already. Then, the development had to start, and this was such complex new technology with the particle system that when they made the first tornado, it didn’t look like anything. The second one was even worse. So it took a lot of trial and error, and it took weeks and even months — we had 300 shots in the movie, and rendering would take 24 hours for every single shot. As you can imagine, the date of the premiere was set in stone, so as [that date] got closer and closer, we added more people working on the project. So they were really worried about it, to be honest.

Stepping into blockbuster filmmaking as a director after working as a cinematographer, what were the rules of that scale of filmmaking then, and how have you seen those change in the movies that you watch now that attempt to have a similar spectacle?

I’ve worked with quite a few big directors, and of course you learn a lot from them. But visual effects [like filmmakers use today] was completely not on the horizon yet. But there were techniques that I felt I could improve on. I wanted to make a movie in which all those things come together perfectly — the visual effects, the special effects, and the on-camera cast. I didn’t want people to look only at a visual effect or only a special effect or only at the landscape. They had to become one. And that was really, really hard to achieve. And we got close, but we never got them all together because the technology really did not exist [at the time] with digital transfers.

When this possibility [of remastering the film in 4K] came up, I said, “I really want to be involved in it.” So with things I didn’t like — and probably most people wouldn’t even notice what I saw, but for me were really disturbing or I hate that didn’t work — I could fix all those things. And now it feels like everything is much more seamless. That’s a problem with a lot of visual effects movies — how do actors possibly respond for real if they haven’t been in that situation? You cannot act in front of the green screen. You cannot see any depth — how do you react to the scope of things in front of you? And that’s why I was absolutely [determined] to make all those techniques come together in one.

The science in this film is, I would say, a little bit exaggerated. What latitude did you experience, or indulge, in depicting the science of tornadoes?

We had scientists on the set every day. We always wanted to make sure, “Is this possible? Could this happen?” And they gave us the most amazing information, and so did the storm chasers. Because it’s one thing to want to make a movie about storm chasers, but what would [their experiences] be like in reality? Who are the people who risk their life to get close to a tornado? So we did a lot of research, and we had several storm chasers with us as well — they are extremists in a way, but for them, it’s also science. I thought they were only doing it for the adrenaline, but it’s not like that at all. Many of them went to the [National Severe Storms Laboratory] in Oklahoma, and that’s where we got a lot of images from.

Helen Hunt got struck in the head during filming, and she and Bill Paxton were temporarily blinded by electronic lamps. Cinematographer Don Burgess left and was replaced by Jack Green, who was injured in the hydraulic house set. When you experience some tumultuous elements throughout a production, is there a moment when those difficulties fade away, amends get made, or that makes all of those difficulties worth it?

All of that happened within a week. I wanted a handheld, really active environment, and [Don] was more interested in static cameras and beauty shots. To me, the beauty would express itself when it all came together. Even Spielberg said, “That has to change.” But that was actually very quickly solved — it was not a big of a thing as it was made out to be. But it was a really hard shoot physically. It was draining because we were in a territory where we never knew if it was going to rain or be sunny, so we often had to change location in the middle of the day. Those additional problems happened on a very regular basis. And because the movie takes place in one day but shooting takes place over multiple months, in the beginning everything is barren and then slowly the corn comes up and the trees start to grow. And before you know it, you have to look for another location that matches the first one. And that went on and on and on — it was really, really tough.

How much, if at all, did Warner Bros reach out to you about “Twisters”?

We only spoke about it about 15 years ago. Warner Bros. could see the potential, but they were very afraid of the cost. So this recent one, I’m not involved in at all — I only found out about it after I saw the trailers on TV! But the movie at that time was a possible sequel was a continuation of the same story with the same people but different circumstances.

What prompted you to step back from directing? “Lara Croft: Tomb Raider — The Cradle of Life” was a modest hit, but it was a hit.

It made money — I’m still getting paid for it. But I don’t know. I had some really great projects — one was “Riders in the Sky,” about Indian tribes in the Midwest. It was a beautiful story, very imaginative. I really would’ve loved to make it. I also would’ve loved to make “Godzilla.” I’m a huge fan of “Godzilla” — to me, [“Godzilla Minus One”] is one of the best movies ever. But projects get postponed, and it becomes really tiring to work on a project for so long.

For “Riders,” we already had locations. We were designing sets. And with “Godzilla” too, we had sets ready. The people in Japan were very excited. I really loved the guys who played Godzilla. And then [Sony Pictures] suddenly said, “It will be too expensive.” And Roland Emmerich said that his movie was going to be much cheaper. Of course, that was a lie — it became much more expensive than my budget. But when minds change at the studio, you can’t really do anything about it. It’s just a pity because we had a really great script — it would’ve been great.

Do you still harbor the same passion cinematography or directing that you once did?

There’s still some ideas that I have that make for a really exciting movie. I mean, one [more] would be good.

Best of Variety

'Blue Velvet,' 'Chinatown' and 'Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas' Arrive on 4K in June

'House of the Dragon': Every Character and What You Need to Know About the 'Game of Thrones' Prequel

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.