‘They’ve had 50 years to figure it out’: Title IX disparities in major college sports haven’t gone away

Led by a two-time national player of the year and firmly entrenched at the top of the rankings, the Oregon women were college basketball’s version of rock stars during the 2018-19 and 2019-20 seasons.

The Ducks had Sabrina Ionescu, a Kobe Bryant protégé who now appears in State Farm commercials. Fans packed arenas at home and on the road, hoping to see records fall. Oregon’s No. 1 ranking at the beginning of the 2019-20 season was the first in school history, for either the men’s or women’s basketball team.

Yet as the less successful Oregon men’s team took charter flights to a majority of its away games those two seasons, Ionescu and her teammates mostly flew commercial. It wasn’t uncommon to see them schlepping through airports alongside business travelers and vacationers and folding their tall frames into economy seats.

About the series

USA TODAY’s “Title IX: Falling short at 50” exposes how top U.S. colleges and universities still fail to live up to the landmark law that bans sexual discrimination in education. Title IX, which turned 50 this summer, requires equity across a broad range of areas in academics and athletics. Despite tremendous gains during the past five decades, many colleges and universities fall short, leaving women struggling for equal footing.

“I think that we've just gotten used to kind of playing with less: not as cool of jerseys or less jerseys or less food, worse travel, worse hotels. That’s just the norm. That’s what we do every day,” said Oregon junior Sedona Prince, who was a redshirt freshman in the 2019-20 season after transferring from Texas.

Prince has become a leader in the fight to address inequities after her video about the differences in the weight rooms at last year’s men’s and women’s NCAA tournaments went viral on social media.

“I think it’s sad,” she said, “because we’ve kind of gotten used to being screwed over.”

The Oregon women aren’t alone.

Despite the progress ushered in by the landmark Title IX law, colleges and universities consistently devote fewer resources to women’s sports than men’s, based on the results of a first-of-its-kind data analysis by USA TODAY in collaboration with the Knight-Newhouse Data project at Syracuse University.

The analysis uses NCAA revenue and expense reports for the 2018-19 and 2019-20 seasons to compare what 107 public schools in the Football Bowl Subdivision – the highest level in Division I – spent on travel, equipment and recruiting for similar men’s and women’s teams.

For every dollar schools spent on men, the analysis found, they spent just 71 cents on women in those categories. Over two seasons, that added up to $125 million more for men than women in basketball, baseball and softball, golf, soccer, swimming and diving, and tennis.

USA TODAY focused solely on sports with comparable men’s and women’s squads. Had the analysis covered all teams, including football, the overall disparity would be greater: Altogether, schools spent just over twice as much on men than women on travel, equipment and recruiting combined – $1.16 billion compared with $576 million.

The spending chasm underscores the broad failures of top U.S. colleges and universities to fully comply with the mandates of Title IX. The law, which turns 50 this summer, requires schools receiving public funds to ensure gender equity across a range of areas, but it is probably best known for its mandate to provide women equal athletic opportunities.

Yet, five decades later, schools are still falling short.

Colleges and universities spent millions more on men’s teams in every category across four of the six comparable sports. Only soccer and swimming spent roughly equal amounts. On travel alone, schools collectively spent 40%, or $77 million, more on their men’s teams. On equipment, they spent nearly 40% more, or $26 million. And on recruiting, schools spent 51%, or $22 million, more for men’s teams.

“Title IX provided opportunities for girls and women to have the same opportunities as our male counterparts. We’re here 50 years later, but we still are not treated in the same manner,” said Dawn Staley, the women’s basketball coach at the University of South Carolina.

The disparities were glaring in baseball and softball, golf and tennis. But nowhere more so than basketball, for which coaches and athletic departments spent 63 cents on women for every dollar on men. Among the findings:

Of the 107 schools, all but two – the University of Hawaii and the University of Toledo – spent more on travel for men’s basketball teams, including 19 that spent at least $1 million above what they spent on women’s teams. Even schools considered standard-bearers for women’s sports shortchanged their female athletes. The University of Connecticut has won a record 11 titles in women’s basketball and has the two longest winning streaks in NCAA Division I basketball. Yet it spent over $800,000 more on travel for its men’s team, and nearly $1.2 million more overall across the three spending categories.

Schools collectively shelled out $8.7 million – or 39% – more on equipment for men’s basketball than women’s. Louisville, for example, spent 13 times more on the male players – $327,000 compared with $24,000 for the women. That included a single purchase at a local sporting goods store for $9,705 worth of clothing like shorts, tights and pullovers. They spent more than $2,500 on socks alone.

On recruiting, schools spent a total of $19 million – or 72% – more to lure top talent to their men’s basketball programs. Indiana University spent $1.2 million for its men’s basketball team, nearly six times more than the $216,513 spent by the women’s team. The men’s expenditures, according to detailed records obtained by USA TODAY, included more than $650,000 for charter flights and $12,000 for car services for recruits. There were no similarly labeled charges for the women’s team.

"The saddest part of all of this is that Title IX has been the law for 50 years, and while enormous progress has been made, the vast majority of schools in this country – colleges and universities in this country – are violating Title IX by treating their male athletes, as a whole, way better than their female athletes, as a whole,” said Arthur Bryant, an attorney who has been litigating Title IX cases for decades. “That's a straight-out violation of Title IX, and it needs to stop."

USA TODAY interviewed 21 current and former coaches, athletes and athletic directors from 10 schools, as well as eight Title IX experts, for this story. The media organization also filed public records requests for detailed expense reports from more than a dozen schools and pored through hundreds of pages of purchases to get a better picture of how they spent money.

Some colleges and universities declined to comment on the spending gaps. Those that did offered several explanations for the disparities, including the men’s team advancing further in the NCAA championships, as was the case for Michigan State in 2019, said its associate athletic director Matt Larson.

Still, Michigan State far outspent the other teams in the men’s Final Four on travel that year, by $900,000 more than Texas Tech and over $2 million more than Virginia and Auburn. The NCAA pays for postseason travel costs up to a certain dollar amount, but schools are responsible for any additional expense.

Others said the spending imbalances reflected the wishes of the women’s team. Patrick McKenna, UConn’s senior associate athletic director, told USA TODAY that the women’s basketball team “preferred to operate with a smaller travel party during road trips” in the 2018-19 and 2019-20 seasons, so it took smaller, less-expensive planes than the men’s team.

Inside the numbers: Searchable data offers glimpse into how colleges short-change women’s sports

“During the 2021-22 season, the women’s basketball team chose to fly on a larger plane, so the difference in men’s basketball and women’s basketball travel expense will be smaller,” McKenna said.

Still others blamed the situation, in part, on restricted donor funds that pour money into men’s athletics programs but not women’s.

“I think that's one of the hardest parts of college athletics as a whole,” said Josh Heird, the interim athletic director at the University of Louisville. “Over the years, football, men's basketball tend to garner more support. There's just more donors that want to be associated with those programs.”

But experts said those excuses don’t erase the mandate of Title IX.

“As far as Title IX is concerned, as far as gender equity is concerned, it doesn't matter the source of the funds or the benefits,” said Sarah Axelson of the Women’s Sports Foundation. “As soon as a school allows for that benefit to be passed along to its student athletes, it is required to make sure that it provides an equitable experience.”

Part of the problem, several women’s coaches told USA TODAY, is that they often don’t even know about the inequities. Or, if they do, they don’t realize the extent of them because no one is telling them. When the full scope of the imbalances are brought to light, it is hurtful and exhausting, some said – just one more way in which women are told they don’t matter.

“It’s really demeaning,” said UCLA coach Cori Close, who is also president of the Women’s Basketball Coaches Association. “Just think about how women already feel like less than and then add that this is a sport with predominantly women of color.

“What does that feel like?” Close asked. “Think about how hard they have to fight for their own inner self-worth. They shouldn’t have to fight that hard.”

Compliance with Title IX is generally based on a school’s entire athletic department rather than specific teams, and the U.S. Department of Education requires that spending on similar teams be equitable rather than equal. That means the dollars spent don’t have to be exactly the same, so long as the experience and treatment of the athletes is comparable.

But because schools typically devote an inordinate amount of resources to football, they then need to find other places to spend on female athletes so they can close the equity gap. If similar men's teams are still receiving more resources, that can reflect a difference in treatment. And that, experts said, could then suggest problems in complying with Title IX.

“The red flags that you always look for is to compare the operating budgets of same sports to same sports,” said Donna Lopiano, who was the first director of women’s athletics at the University of Texas before serving as the CEO of the Women’s Sports Foundation from 1992 to 2007.

In her consulting business, Lopiano serves as an expert witness in court cases – often for plaintiffs suing schools for Title IX violations – and does Title IX compliance reviews for athletic departments.

“When you see these big disparities,” Lopiano said, “they are red flags.”

Spending disparities are not as blatant as they were in decades past. Coaches are not washing the uniforms of their players as Pat Summitt, who eventually became the first women’s basketball coach to make $1 million a year, did early in her career at the University of Tennessee. Female athletes are not banished to basements to practice, or using metal lockers with no doors and that saw their last coat of paint in the Nixon administration.

But college athletics, for almost the entirety of its first century of existence, meant men’s sports. The law might dictate that women be treated equitably, but systemic discrimination remains baked into the structure.

“If people, meaning athletic administrators and college presidents, wanted to be in compliance with Title IX because it was the right thing to do, they would've done it already,” said Nicole LaVoi, director of the Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport at the University of Minnesota.

“They've had 50 years to figure it out,” LaVoi said. “So there's no, ‘Well just give us time. We'll figure it out.’ No, they've had 50 years. And so many schools are still struggling with this.”

Nobody is looking at the numbers

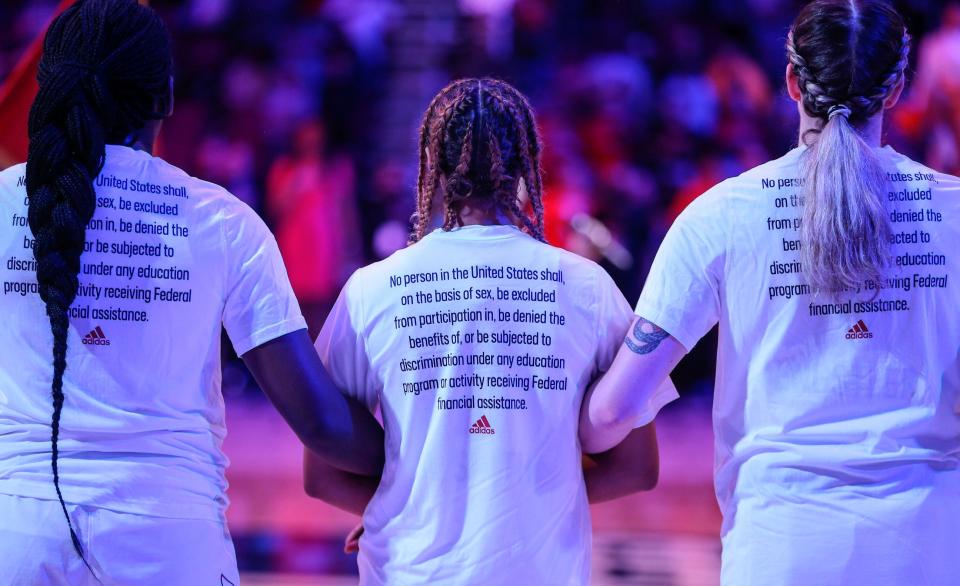

Enacted on June 23, 1972, Title IX prohibits sex-based discrimination by any “education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.” The law was initially meant to open the doors of higher education to women, particularly in graduate schools.

But resistance from athletic departments prompted the bill’s authors to ensure the same rules applied to athletics. Over the next three years, what was then known as the Department of Health, Education and Welfare drafted regulations that required schools to provide equal opportunities for women athletes.

Title IX proved to be a watershed. Within two years, the number of high school girls playing sports soared from fewer than 300,000 to 1.3 million, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations. The number of women playing sports in college went from 32,000 before Title IX to a little more than 224,000 in 2019-20.

The increases in girls and women playing sports has an impact beyond athletics. Studies show that women who play sports are healthier, get better grades and have higher graduation rates. An ESPNW and Ernst & Young survey of 400 female corporate executives in 2015 found that 94% had played sports, and that wages for women who had played sports were 7% higher.

But while women eagerly take advantage of the increased opportunities, schools almost universally lag behind in ensuring that they are equitable.

“The vision, perhaps naively, was that people would recognize both the right of girls and young women to have athletic opportunities and the value to them to having those opportunities. And the value to the country of having athletic opportunities and discipline and the good parts of athletics to be available,” said Jeff Orleans, who helped write the Title IX regulations in the 1970s as an attorney for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare and now specializes in higher education law.

“And that, over time, people would grow into compliance and grow into a culture of equality.”

But last year’s NCAA basketball tournament exposed how far colleges and universities are from that culture of equality.

Images showing the small rack of dumbbells provided to the women’s teams at the March Madness tournament in Texas compared to the sprawling weight room at the men’s event in Indianapolis shined a light on the disparities that players and coaches last year said was typical of the treatment they endure.

"If you're not upset about this problem, then you’re a part of it," Prince said at the time.

Although anger was directed at the NCAA, such problems exist at campuses across the nation, including Oregon, USA TODAY’s data analysis found.

The Ducks spent nearly $50,000 more on equipment for its men’s basketball team than the women in 2018-19 and 2019-20.

Oregon also spent over $132,000 more on recruitment for men’s basketball compared to women and $702,300 more on travel.

Oregon declined to make athletic director Rob Mullens available for an interview about the travel spending disparities. In an emailed statement, its athletic department spokesman, Jimmy Stanton, said they “continually increase investment in high levels of equitable support for all student-athletes, and as NCAA legislation has become increasingly permissive toward student-athlete support, we have allocated additional resources to benefit all student-athletes.”

When presented the numbers by USA TODAY, Ducks women’s basketball coach Kelly Graves said he thought the men’s and women’s programs were being treated equitably and was surprised at some of the spending gaps.

He’s not alone. Most women’s coaches told USA TODAY that they don’t see the budgets for the men’s team, nor do they specifically track what the men’s team is doing or getting. It’s often only by happenstance, they said, that they learn of disparities in treatment.

It has been that way for decades.

Muffet McGraw, who led Notre Dame to two national titles and seven other trips to the Final Four during a three-decade career that earned her a spot in the Hall of Fame, recalled once hearing that the university was providing the wife of the men’s basketball coach with a car. When she asked why a similar offer hadn’t been made to her husband, McGraw said, she was told, “We were wondering why you hadn’t asked about that.”

“So I’ve got to be a detective and find out what I’m not getting? I had to stumble upon something in order to get it, rather than them just freely acknowledging it,” McGraw said.

USA TODAY found that almost nobody is looking at the numbers.

The Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act requires schools to submit annual reports detailing the number of men’s and women’s teams they field, as well as the staffing and spending for each. In theory, that could be a tipoff to the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights that schools might not be complying with Title IX.

But the DOE is largely reactive when it comes to Title IX violations. It acts primarily upon complaints rather than proactively policing schools to ensure they’re meeting their obligations to the law. Even when violations are found, schools know the penalties will be largely toothless. The agency gives schools multiple chances to remedy their failings, and has never stripped anyone of all federal funding.

“It’s not the law itself,” said Debbie Yow, who spent almost three decades as an athletic director at Division I schools. “Maybe after all this time, the Office for Civil Rights needs to go back and say we need to do a review. Does it work? Does how we determine people can satisfy Title IX obligations and what we say we need to do (work)?

“It seems like the discussion would be healthy at this point in time.”

Leaving money on the table

On average, men’s college sports generate more revenue through ticket sales and TV rights than women’s sports – CBS and Turner Broadcasting are scheduled to pay $11.4 billion alone for the multimedia and marketing rights to the NCAA Division I men’s basketball tournament through 2032 – and this has often been used to justify the spending disparities.

But a growing number of college sports leaders say the argument ignores the fact that men’s programs have had a decades-long head start in terms of support and promotion.

Men’s programs also receive most of the spotlight, even though the investors and sponsors flocking to the WNBA, National Women’s Soccer League and the NCAA women’s basketball tournament over the last few years have shown that women’s sports can be a moneymaker, too.

By not maximizing their women’s programs, schools are leaving money on the table.

As part of an independent assessment of the disparities at the NCAA basketball tournaments, media expert Ed Desser estimated that broadcast rights for the women’s event could fetch between $81 million and $112 million a year in 2025. That’s more than twice what ESPN currently pays for a package that lumps the women’s event in with championships for more than two dozen other sports.

“This isn’t about slicing the pie differently, this is about letting women contribute so we can make the pie bigger,” said Close, who in her role as president of the Women’s Basketball Coaches Association met weekly with Kaplan Hecker & Fink LLP, the firm that did the assessment for the NCAA last year.

“I want people to say, ‘Wow, women’s basketball is really helping our athletic department, we need to invest in them because it’s a good business decision,’” Close said. “People say, ‘women’s basketball doesn’t bring in any money’ – well, you didn’t invest.”

Even at some of the most successful women’s programs in the country, schools aren’t investing the way they do with men’s teams.

Take the Louisville Cardinals. The women’s team made this year’s Final Four, its third trip in the past 10 years and fourth since 2009, all under the leadership of head coach Jeff Walz. The Cardinals played for the national title in 2009 and 2013.

Walz, who has coached the team since 2007, said the university provides him the resources his team needs to be successful.

“As long as our needs are being met, our student-athletes' needs are being met, they have good care, medical care, trainers, all of that, the coaching is what they deserve,” Walz said, “then I'm fine with that.”

And yet, the USA TODAY review found, Louisville doled out nearly $2 million more on the men than the women across the three spending categories during the 2018-19 and 2019-20 seasons.

For equipment alone, it spent 13 times more on men. Though some of the purchases are communal – the two treadmills, a Stairmaster, three Versaclimbers, two Ropeflex Tower Units, dumbbells and a weight rack purchased in 2019 by the men’s team at a cost of $74,000 are used by both teams – there are plenty that are not.

That same year, 2019, the Louisville men’s team bought nearly $24,000 worth of camera equipment, including microphones, LED light kits, a digital camera, mounts and batteries. Not only does his team not use that equipment, Walz said, his audio/visual staff is a third of the size of the men’s, with his video person also doing graphics and taking photos.

Walz’s team did purchase some electronics: a MacBook Pro, three iMacs and two iPads. But the cost was only $5,794, and it was the largest purchase the women’s team made over the two years examined by USA TODAY.

Louisville's men also got about $1.2 million more for travel during those two seasons than their female counterparts, spending data show.

Walz said some of that disparity comes from his own frugality. He described himself as a penny pincher whose program takes “great pride in not wasting.” For example, he said, he decided to fly commercial for a trip out West during the Thanksgiving holiday last year, even though his team always charters to conference games.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

“I could have requested to charter that trip, but I am sitting here going, ‘So I can take a Southwest flight and go from Louisville to Midway, direct to Seattle, for $220 a ticket. Or I can ask to spend $180,000. To me, you can't justify that,” Walz said. “So we just flew commercial. It was not a problem.”

That attitude is not unusual among coaches of women’s teams, said McGraw, the former Notre Dame coach. Whether it is a carryover from the decades spent having to make do with less or the intimation that another program – a men’s program – is ultimately footing the bills, McGraw said women’s coaches are conditioned to watch their spending.

But even if coaches and players say they’re getting “enough,” that doesn’t satisfy Title IX compliance, said Neena Chaudhry, general counsel for the National Women’s Law Center. The law recognizes only numbers, not feelings.

“You have to keep in mind that for decades now, women have been socialized, if you will, and taught that they should just accept whatever they get,” Chaudhry said. “You talk to so many women who are just so grateful to play at all. So I think that you can't analyze those kinds of responses, which I totally understand, apart from the culture in which it all exists.”

Coaches, particularly those of high-profile teams, also share a concern that their younger peers or those at less-successful programs are hesitant to point out inequities or ask for more. That they feel they need to have some clout, in the form of winning seasons, conference titles or NCAA tournament appearances, before they can make the kind of demands that coaches of men’s teams do without a second thought.

“I can see young coaches being afraid to go to their administrations with those kinds of questions,” said Graves, the Oregon coach. “It can be, I think, intimidating for young women's coaches, be they male or female.”

In some cases, stereotypical perceptions fuel the imbalances, coaches and athletes told USA TODAY. The idea that male athletes eat more, so schools will spend more to feed them, or that women don’t need charter flights – or larger charter planes – because they’re not as big as their male counterparts.

“I have really tall women on my team, too,” said Graves, whose roster this year included four players 6-foot-4 or taller.

Said Prince, who is 6-foot-7: “The men charter because they get more money. It’s as simple as that.”

‘Hey, this is unfair’

Ray Tanner was the baseball coach at the University of South Carolina for 16 years before becoming athletic director in 2012. Being a coach in a sport that doesn’t generate net revenues made him sensitive to spending inequities. It also informed his view that college sports are not a business and cannot be run like one.

Really, though, he sees the spending in his department as a simple matter of fairness.

“They should have the same opportunities on both sides. I have pretty much focused on doing that,” Tanner said. “It’s a philosophical thing. Why would you have disparities when you’re doing the same thing? I believe in equity, I believe in Title IX. But beyond that, I believe in logic. What’s the difference when women go out and play golf and men go out and play golf? There is none.”

South Carolina is an outlier.

It was one of only five schools that spent at least 95 cents on women’s teams for every dollar spent on men’s teams in the comparable sports that USA TODAY examined.

In basketball, the women’s team spent more on equipment than the men – to the tune of $45,000. Staley and her staff also spent nearly $25,000 more on recruiting than the men’s team, an anomaly even among other high-profile programs.

At Louisiana State University, by contrast, the men’s basketball team spent $1.1 million more on recruiting than the women during the 2018-19 and subsequent season – the biggest disparity of any school.

University of Kentucky, Texas A&M University and Indiana weren't far behind, with the men all spending slightly over $1 million more.

Indiana’s athletic director since 2020, Scott Dolson, said supporting women’s athletics is a top priority and led to the creation of the IU Athletics’ Women’s Excellence Initiative.

“In our work to find and address disparities,” Dolson said in a statement to USA TODAY, “we had already added funding for our women’s basketball head coach to utilize charter air when necessary in recruiting during the 2021-22 season.”

At South Carolina, Tanner’s attitude sets the tone. But he said he also requires the department to be intentional about maintaining equity; budgets are monitored and compared. South Carolina also brings in Janet Judge, an outside Title IX expert, two or three times a year to keep the Gamecocks on track.

The biggest check, though, comes from the athletes themselves.

“Our student-athletes feel really good about their opportunities, how they get treated, and it doesn’t matter if someone is playing beach volleyball or is one of our football players,” Tanner said. “They don’t feel they’re different types of athletes, they don’t feel they’re treated differently. That stigma doesn’t exist. And I’m proud of that.”

Female athletes, and the men and women who coach women’s teams, say they have never asked for special treatment. Or to be given things their male counterparts are not. They simply expect things will be fair, just as they expect when they step on the court or the playing field.

But fairness will remain elusive so long as colleges and universities consistently provide their men’s teams with more resources.

“The important point is Title IX does not require schools to spend equal amounts on women and men. It requires them to give women and men equal treatment,” Bryant, the attorney who has brought Title IX cases, said.

“But particularly in a capitalist country like America, when you're spending unequal amounts, you're usually providing unequal treatment. And particularly when the disparities are massive, as they are in some of the cases you've cited, then the violations of Title IX are pretty darn clear."

For Prince, it’s not about one particular disparity or one memorable instance: It’s a system that continually diminishes female athletes.

“It’s the buildup of it since we were young girls playing basketball,” she said. “It’s not just one thing. It’s this anger that builds up inside of you when you play women’s sports throughout your entire career of, ‘Hey, this is unfair.’”

Prince admits she wasn’t that familiar with Title IX before her video went viral. Her generation is the first to grow up with equal opportunities in athletics and education as the norm, and she calls the law that paved the way for that “super cool.”

But she is annoyed that, 50 years later, there is still such a long way to go.

“Honestly, I want us to stop talking about this,” Prince said. “I think that’s when we’ll know that we’ve actually made progress, when inequity isn’t a conversation topic anymore.”

Contributing: Rachel Axon, Dan Wolken, Dan Keemahill, Teghan Simonton, Alyssa Hertel and Emily Barnes

The team behind the Title IX series

Reporting and analysis: Nancy Armour, Rachel Axon, Steve Berkowitz, Alia Dastagir, Kenny Jacoby, Jessica Luther, Lindsay Schnell, Dan Wolken

Data and public records: Matthias Ballard, Emily Barnes, Emma Cail, Doug Caruso, Max Chadwick, Noah Cierzan, Zshekinah Collier, Daniel Connolly, Ruth Cronin, Elizabeth DeSantis, Caroline Geib, Laura Gerber, Janzen Greene, Daniel Gross, Alyssa Hertel, Porter Holt, Allie Kaylor, Dan Keemahill, Sabrina Lebron, Brian Lyman, Kyle Loughran, Patrick McCarthy, Haley Miller, Tyreye Morris, Marco Moy, Nicolas Napier, Teghan Simonton, Kayan Taraporevala, Lauren Ulrich, Jodi Upton, Dian Zhang

Editing: Peter Barzilai, Chris Davis, Emily Le Coz, Matt Doig

Digital design and illustration: Andrea Brunty

Project management: Annette Meade

Graphics: Jim Sergent

Photo and video: Jasper Colt, Hank Farr, Chris Pietsch, Stephen Maturen, Brooke Lavalley, Robin Chan, Michael Swensen, Ken Oots, Di'Amond Moore

Social media, engagement and promotion: Nicole Gill Council, Casey Moore, Erin Davoran

Explore the series

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Title IX 50th anniversary: Women short-changed in major college sports