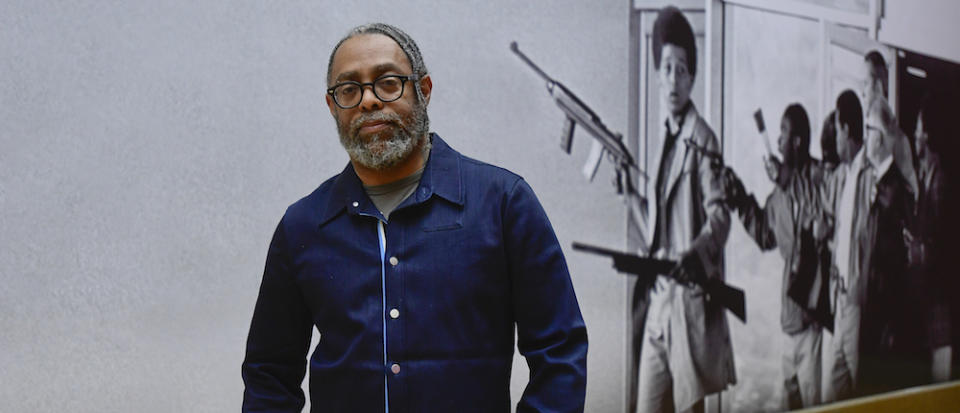

Arthur Jafa Is the Archivist of Black Visual Culture

Arthur Jafa’s work as a cinematographer, visual artist, and cultural theorist, has captured and interrogated the history and experiences of black Americans, in groundbreaking film and visual media, for 30 years. Jafa’s work has exemplified the black aesthetic in stories of a Gullah family’s migration (the touchstone “Daughters of the Dust”); a young girl’s coming of age (“Crooklyn”); a meditation on blackness and culture (“Dreams are Colder than Death”); and the tracing of African American identity through a wide range of contrasting imagery (“Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death”). Through his work, Jafa aims to centralize the varied experiences of “Black being,” as an aesthetic that is entirely independent of Eurocentrism. Oscar and Emmy nominee Bradford Young refers to Jafa (along with Malik Sayeed) as both a torchbearer and teacher of a tradition. “They mean so much to me on multiple levels, and most of it isn’t even about the cinematography,” Young told IndieWire. “They teach that the intention behind the image means more than the image itself. If the intention is in line with the tradition, then ultimately the image will do what it needs to do, which is to speak to people in a certain way and give them a feeling.” The tradition he refers to is one in which the systemic disadvantages that black filmmakers have historically faced, are acknowledged and understood, but aren’t necessarily seen as limitations to dwell upon, and are instead motivation to enter other spaces that allow for more creative freedom. “AJ was very much the baton carrier of that tradition, and all the work that I’m doing is to make sure that I stay in line with the tradition, so that I could be a baton carrier as well,” said Young. “We were never just cinematographers, or just filmmakers. We are ultimately visual artists, and we take on anything that will allow us to represent ourselves visually, whether it be through single channel installations as you see with ‘Love Is the Message’, where AJ is actually archiving material in order to continue the conversation. He is really leading us by example.” Jafa’s ambitions can be partly traced to his Mississippi Delta roots, a region that is considered the birthplace of several genres of black music, including the blues and rock and roll. His rigorous pursuit of a black visual aesthetic is inspired by the demonstrative possibilities of black music, and he wants to give black images the same agency that black music has developed through its cultural clout. What he calls “black visual intonation” would be the image’s way of communicating blackness in the same way that the music has done. And from his collaborations with popular musicians, including Solange, on visuals for her album “A Seat at the Table,” to directing the music video for Jay-Z’s “4:44,” Jafa presents “Black being” in all its multilayered complexity, equally joyful as it is painful; beautiful as it is terrifying; alienating as it is virtuosic.

Jafa’s visual masterpiece “Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death,” a discovery by an artist with decades of influence on black visual language, captures those contrasts. A combination found footage and original film that traces African American identity through 100 years of imagery, the 7-minute short juxtaposes footage of black trauma with images of joy and triumph. The arresting montage is a visceral experience that probes and reclaims the mainstream narrative around black life. There’s an anxiety about an ephemerality of blackness, and an urgency in affirming that which is in danger of being lost: authentic black cultural expression. At the beginning of Jafa’s “Dreams Are Colder Than Death,” African American literary critic and scholar Hortense Spillers says: “I know we are going to lose this gift of black culture unless we are careful.” Jafa’s work serves as an archive set up for the recollection and documentation of that culture. And through his ongoing interrogation of the cinematic form, a new generation of black filmmakers like Terence Nance and Ja’Tovia Gary, are inspired to reconsider the idea of blackness and its aesthetics, politics, history, and conventions, and ultimately contend with Spillers’ concern. —Tambay Obenson

More from IndieWire

Cinematographer Bradford Young Embraces the Dark Side of Digital

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross Pioneered a New Sound for Hollywood Scores

Best of IndieWire

Where to Watch This Week's New Movies, from 'The Equalizer 3' to 'Perpetrator'

The Best Survival Movies, from ‘Cast Away’ and ‘The Revenant’ to ‘The Martian’ and ‘Alive’

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.