Climate change can amplify big rainstorms, but true fixes are far off for South Florida

Once again, South Florida was submerged under an unsettling amount of water this week, the kind of totals usually only seen during a tropical storm or hurricane.

An early June system dumped a month’s worth of rain in a single day on Miami and Fort Lauderdale on Wednesday. Then it did it again the next day.

Experts say climate change could be partly to blame and that the massive flooding across the region proves South Florida’s drainage system isn’t up to the challenge of a warmer, wetter world.

All told, the worst-hit spots saw 20 inches of rain this week alone. It was bad enough to swamp hundreds of cars, block travel on parts of Interstate 95 and delay flights at both major airports.

This is at least the fourth serious flood event in South Florida in as many years, and only one was connected to a full-fledged tropical storm. Scientists say this could be the new normal as human-caused climate change cranks up the temperature around the globe.

“What we are seeing lately is very consistent with what we would expect to see in a warmer world,” said Jayantha Obeysekera, head of Florida International University’s Sea Level Solutions Center. “This is a sign of things to come.”

And yet, despite new real estate developments blooming like mushrooms along the coast by the day, South Florida’s built environment is already overwhelmed by current challenges — before the extra 2 feet of sea level rise expected by 2060 even arrive.

The South Florida Water Management District, which oversees drainage throughout the region, saw gaps in its system near the Miami International Airport, where the agency had to deploy four temporary stormwater pumps to supplement the permanent pump stations in the area.

In western Miami-Dade and Broward, county-run canals overflowed into streets and yards, and cities deployed dozens of temporary pumps and roving vactor trucks to suck up the excess floodwater.

By Thursday morning, most of the liquid evidence of the storm had evaporated, but streets in hard-hit areas were lined with soggy belongings and appliances. There was no formal count of waterlogged homes or cars, but early estimates include dozens of flooded homes and more than a thousand swamped cars.

With the help of much-needed sunlight to dry things up, it became clear that this week’s deluge didn’t match up to the “1-in-1,000” year event in Fort Lauderdale last April, which inundated hundreds of homes and sent people scrambling to shelters, with 25 inches of rain in a single day.

In Hollywood, which saw 20 inches of rain in two days, this week’s event counted as a 1-in-200-year storm, or a rain event with a 0.2% chance of happening any given year.

But, experts say, climate change may be making those events more likely than the “200-year” moniker makes it sound.

Why it happened

The trouble with that much rain is that South Florida’s drainage systems simply aren’t designed to handle it.

The water management district’s system is designed to handle about 6 to 8 inches of rainfall in a single day. Fort Lauderdale, which saw significant flooding, has roads designed to stay dry under about 3 inches of rain a day — up to 7 inches for some of the newly redesigned roads.

It’s the same story in Miami, where the $3.8 billion plan to upgrade all the city’s drainage efforts by 2060 would result — if all goes according to plan — in a city that could handle 7 inches of rain in a day. To get to a capacity of 11 inches a day would require an even beefier investment of $5.1 billion.

And despite tens of millions of dollars of investments underway and on tap throughout South Florida, it could take decades to get every community up to speed to even that level.

Then comes storms like this week’s, which dropped about a foot of rain in a single day in the worst-hit spots.

The problem is the standards that cities and counties are building to are lower than they need to be because they don’t account for the impact of sea level rise, said Obeysekera, from FIU.

“These rules and standards, they’re obsolete in my opinion,” he said. “We need to plan our flood control systems for events like this.”

Obeysekera is the lead on a research team housed at the Florida Flood Hub at the University of South Florida that is working to do just that, figuring out a good estimate of how much higher rainfall levels local governments should be building toward.

The report is still in draft form, but Obeysekera said the climate models suggest extreme rain events in Florida could get 10% to 20% more intense in the coming decades.

Few local governments account for climate change magnification of rainfall, but Broward County is planning for rain events to be 20% more extreme in decades to come, and the water management district is preparing for about a 10% to 20% increase in intensity, depending on the storm and county.

However, unless those modifications for future conditions become required by law, Obeysekera worries that new construction projects won’t be built to those specifications.

“Unless the rules are changed, I feel like developers won’t be interested in using them because they’re not required,” he said.

Warmer air is wetter air

Finding the ‘”right” figure to use for future rainfall levels is difficult, but it’s based on a couple of factors. For one, there’s the uniquely South Florida factor of what’s below our feet.

South Florida, unlike other parts of the country, does not sit on solid bedrock. Below the surface is something called oolitic limestone, a porous rock that allows groundwater to rise to the surface rapidly. And research has shown it rises along with sea levels, which is why solutions like sea walls won’t protect Miami from rising seas.

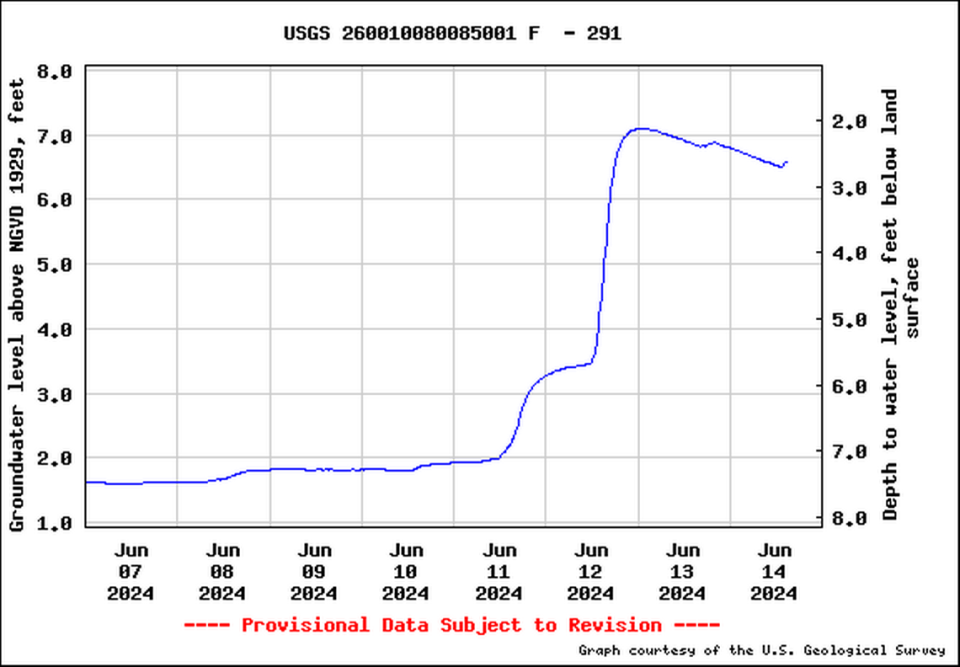

When the rain started on Tuesday, groundwater levels jumped nearly 5 feet in two days, according to groundwater well data from spots in east Hollywood and North Miami. At its highest point, groundwater was a mere 2 feet below the surface in Hollywood; in North Miami, it reached the surface.

As sea levels rise, that extra space between groundwater levels and the surface disappears, which makes it easier to trigger another flood with even less rain. South Florida has already seen about 7 inches of sea level rise in the last 30 years, said John Morales, the hurricane specialist at NBC6.

“You don’t think those 7 inches matter? They matter a ton. There is much less storage underground,” he said. “It floods easier. In 10 years it won’t take a 1-in-100-year storm, it will just take a 1-in-50.”

And then there’s the warming.

The world is already one degree Celsius hotter than it was a century ago. Basic physics show that as air warms, it’s able to hold more water. So those purple-gray storm clouds that sweep over South Florida on summer afternoons have even more juice to squeeze out of the atmosphere in the form of rain.

Exactly how much more juice, though, is hard to say.

Understanding how climate change will affect rainfall — particular in Florida, which is surrounded by water on three sides — is tricky business. Global-scale climate models aren’t great at understanding the intricacies of Florida’s famous summer afternoon rainstorms, Morales said — so much so, that climate models have trouble predicting whether rising temperatures will dry out the state, causing less rainfall, or whether a humid atmosphere will cause even more rain events.

“It’s unclear whether Florida’s peninsula is going to get wetter from precipitation or drier from precipitation because there is no clear trend,” he said. “What we do know is when it rains, it rains harder.”

Climate change affects the extreme ends of the weather spectrum, Morales said. It makes hot days hotter and wet days wetter.

But, he stressed, scientists do not believe that climate change creates these flooding rainstorms out of nowhere. It simply enhances what’s already happening.

“Climate change did not cause this event,” he said. “Let’s be clear, it did not trigger what happened yesterday, however, the severity of the event got enhanced by climate change.”

When academics run major global climate models, they see that effect.

For instance, Kevin Reed, the associate provost for climate and sustainability programming at Stony Brook University in New York, looked at the impact of climate change on Hurricane Ian, which hit Southwest Florida in 2022.

His paper found that rainfall levels were about 5% to 10% higher, on average, than they would have been in a cooler world. But in the spots that received the most rain, levels were about 18% higher.

“The reality is the world has warmed by over a degree Celsius. Climate change is here. We’re seeing the impacts of that in a variety of events, like this,” he said.