Elliott Erwitt, photographer celebrated for his visual ‘one-liners’ and pictures of dogs – obituary

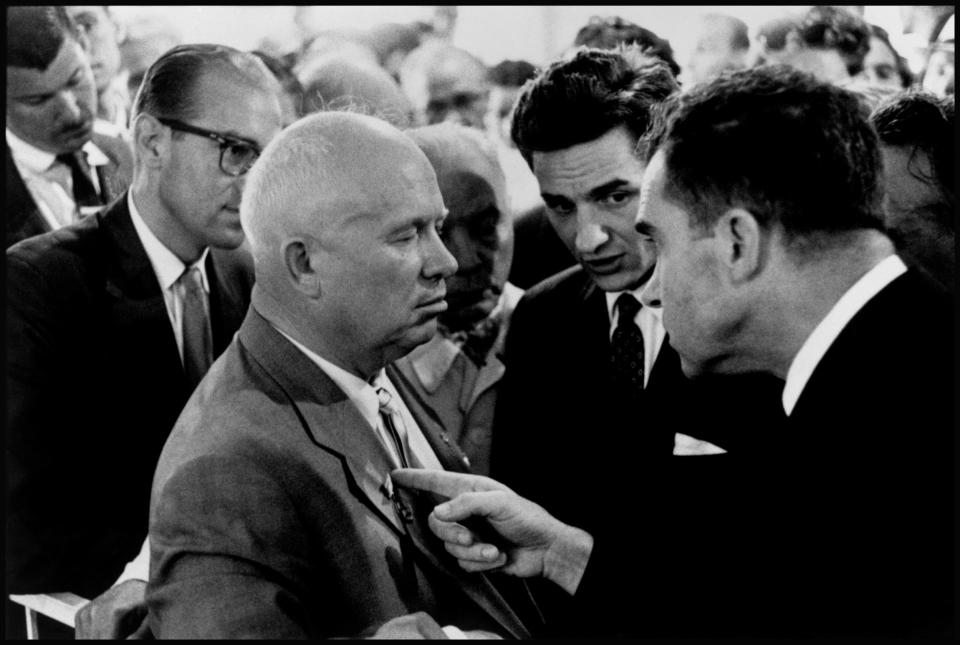

Elliott Erwitt, who has died aged 95, was one of photography’s great humourists, best known for his pictures of dogs; but he was also a revered photojournalist, capable of high seriousness, for instance when documenting Jackie Kennedy’s grief at her husband’s funeral, and more usually mischief, as when he immortalised the “kitchen debate” between Nixon and Khrushchev in 1959.

Erwitt was at the Moscow Fair on an unglamorous assignment to photograph an exhibition of Westinghouse refrigerators, when Nixon, then vice-president, and Khrushchev walked into the display kitchen. Khrushchev began haranguing Nixon, arguing that it was better to have only one model of washing machine than many; Nixon made some disobliging remarks about living conditions in the Soviet Union, and eventually jabbed the Soviet premier with his finger.

By that point, Erwitt was shaking so hard with laughter he almost could not press the shutter, because Nixon was shouting “We eat meat while you eat cabbage!” and Khrushchev was shouting “Go f--- my grandmother!” But the photograph made Nixon look commanding, and it was later used without permission in Nixon’s 1960 presidential campaign – to the Democrat Erwitt’s irritation.

Such vagaries of chance ruled his life, and he refused to subscribe to any other theory of photography. “It’s a crap shoot. It’s a gift when it happens. It’s nothing you can plan on, and it’s not conceptual, thank God,” he said. Some of his best results came from drifting along in a crowd, then turning 180 degrees on his heel, and photographing the people behind him.

He made famous portraits of Marilyn Monroe, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, but his more unusual gift was being able to elevate ordinary American life into something timeless by capturing the visual “one-liner” – nude artists sketching a fully clothed model, a dog navigating a thicket of human legs – in a way that did not feel contrived.

He poked fun at “museumese”, saying: “Photography is so simple that people feel inferior, so they have to invest it with fancy language and, to put it bluntly, bulls---.” He insisted that his own photographs were not about anything in particular, adding as a wind-up: “I think that makes them a little more universal.”

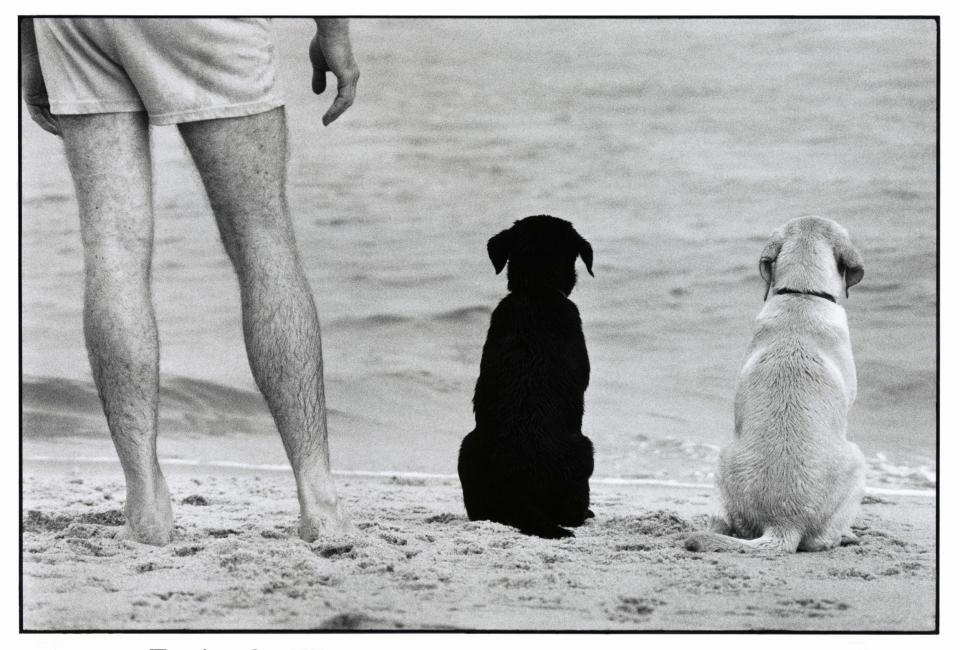

His dog photographs were hailed as “a hilarious mirror of the human condition”, and he did concede that, when photographing dogs, he was really photographing people, whether it was poodles with absurd cuts, or the feet of owner and dog side by side, or simply anthropomorphising an expressive canine face.

“Dogs make easy, uncomplaining targets without the self-conscious hang-ups and possible objections of humans caught on film,” he said. He would barked at dogs to razz them up. His own dog, a cooperative muse, had been trained urinate on command, which helped Erwitt compose a satirical shot of the Brandenburg Gate. “If I really took pictures of people doing some of these things, I’d get into trouble.”

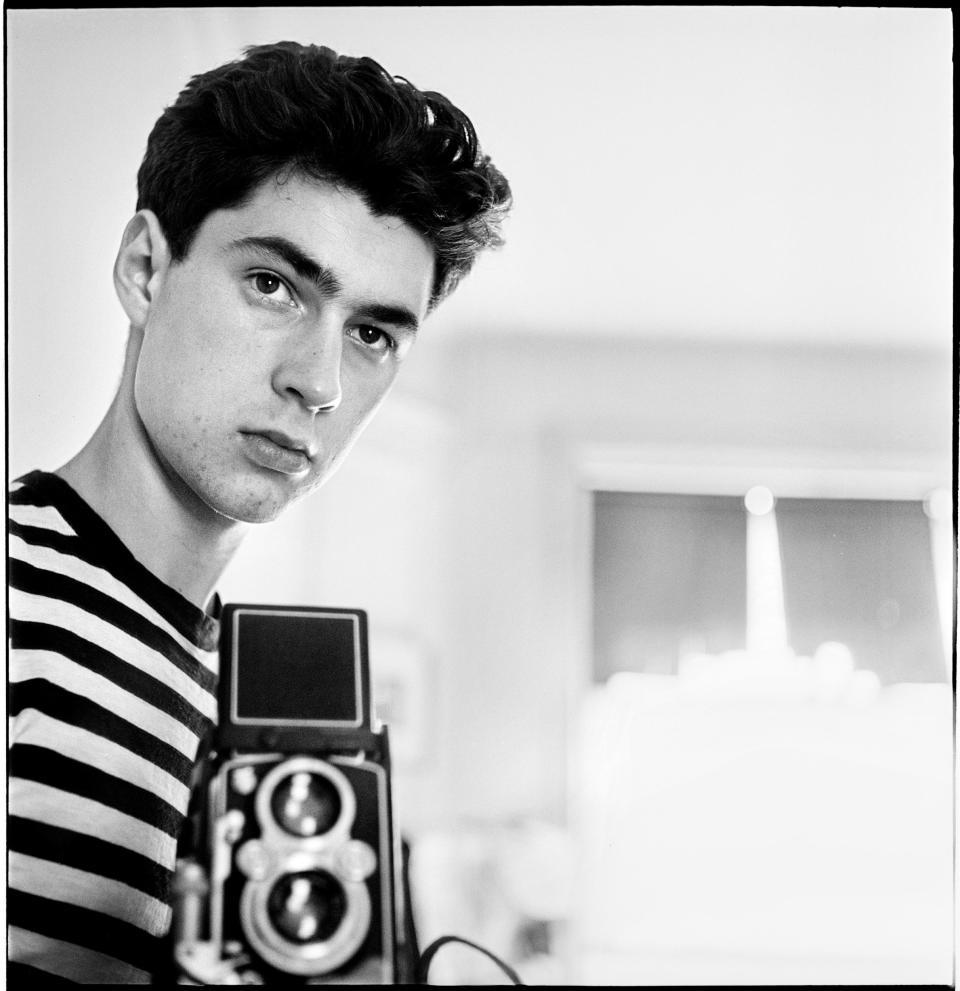

He was born Elio Romano Ervitz on July 26 1928 in Paris to a Jewish father and a Russian aristocratic mother. He spent his first decade in Milan, then in 1939 they fled to New York. The renamed Elliott – who spoke no English – enrolled at a rough-and-tumble school on the Upper West Side. In 1941 he moved west with his father, attending Hollywood High School, with odd jobs as a soda jerk, an usher and in a commercial darkroom.

The camera gave him the confidence of “a mask”: one of his first photographic commissions, aged 15, came from his dentist, who posed by his drill.

In 1948, he returned to New York, where he met the Magnum photo agency co-founder Robert Capa, the photographer and curator Edward Steichen, and Roy Stryker, the man behind the Farm Security Administration’s project to make a photographic record of America in the Great Depression. In 1950, Stryker sent Erwitt to photograph an oil refinery in Pittsburgh, then kept his young protégé there all autumn, documenting race relations in the Steel City.

In 1951, Erwitt was drafted into the Army, serving in the Signal Corps in Germany and France, and took a series of wry photographs of military life called “Bed and Boredom”; one shot won him a $2,500 prize from Life magazine.

In 1953, Capa invited him to join Magnum, and by the late 1960s, the precocious Erwitt had become its president, a post he left after three years, not without relief. He described the photo agency as “a combination of prima donnas”: “Sure, we’re a family,” he said. “That’s why we tear each other’s throats out.”

He was without vanity when it came to his bread-and-butter commercial work, which he kept up his whole life, to pay the alimony (he had six children from three marriages). On one fashion shoot, which involved a monkey, he found the monkey was getting paid $100 more per day than him. If a client wanted it, he would shoot in colour, but the photographs he took for himself were always black and white.

His favourite subjects were couples romancing, people on beaches, and museum-goers absorbed in art (he called it “shooting fish in a barrel”). He would hide the sound of the shutter by coughing, a trick he learnt from Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps, when the assassin waits for a cymbal clash before shooting.

Fluent in four languages, he worked in Europe a great deal, but America suited him best, partly because Americans were less self-conscious. He liked photographing the Deep South, where he sensed an inner hardness masked by good manners. He also fell in love with Scotland, and published a book on it in 2018.

In the 1970s, he turned to film, making documentaries, and in the 1980s made 18 comedy films for HBO.

When asked about reincarnation, he said he would come back as a golden labrador, “running around on the beach, chasing balls, swimming in the ocean. Sounds nice. The disadvantage would be that in 15 years or so, I’d have to look for another venue.”

Elliott Erwitt, born July 26 1928, died November 29 2023