Former US Sen. Lauch Faircloth, a political force for NC Democrats and Republicans, dies

Lauch Faircloth, who worked for Democratic governors before serving a U.S. Senate term as a Republican, died Thursday afternoon. He was 95.

He died from natural causes, said his daughter, Anne Faircloth.

Born Duncan McLauchlin Faircloth in Sampson County, Faircloth became steeped in Democratic politics before he was old enough to vote, helping candidates for governor and working in their administrations.

The first time he put himself out as a statewide candidate, Faircloth lost a Democratic primary for governor but survived a campaign-trip plane crash.

He changed his party designation in 1991 and won a term in the U.S. Senate as a Republican.

Switching from Democrat to Republican

His political evolution was emblematic of the state’s political shifts.

In a 1992 interview, Faircloth said switching parties “became a matter of principle.”

“Here I am an avowed conservative, under the charade of a liberal Democratic Party,” he said. “At that point I knew that I had to make a change.”

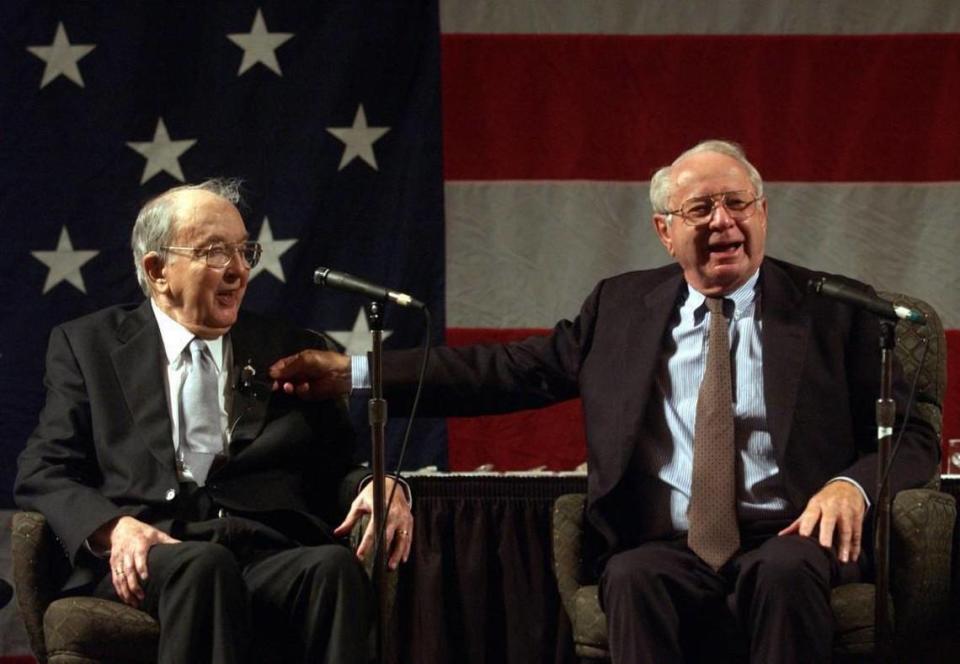

He won the GOP primary and general election with the help of U.S. Sen. Jesse Helms’ political organization, defeating a former close friend and political ally, Democratic U.S. Sen. Terry Sanford.

Faircloth and Sanford didn’t reconcile until 1998, when Sanford was near death.

Prior to his election, he campaigned across the entire state “to meet people that he didn’t know. He knew all the Democrats. He needed to meet Republicans,” said Jonathan Hill, who campaigned with him and later worked as Faircloth’s chief of staff in Congress.

“We traveled about 80,000 miles that year in a car all over North Carolina. We drove east to west, all over. And he knew every town, we never used the roadmap. He had a memory, he had a photographic memory.”

“He’s the smartest man I’ve ever worked with and that I ever knew. It was an honor to work with Lauch Faircloth. He was a great man,” said Hill.

‘Workfare’ was Faircloth’s signature issue

A Senate aide of Faircloth, Ted Brown, told The News & Observer that “Faircloth was my employer, but more importantly my friend.”

Brown said Faircloth “placed great value on everyday people’s opinions.”

“Lauch would ask, ‘What do you think and what would you do?’” Brown said. “Learning other’s thoughts and opinions to develop your own certainly defines leadership. It didn’t matter your social-economic status. He was truly a public servant.“

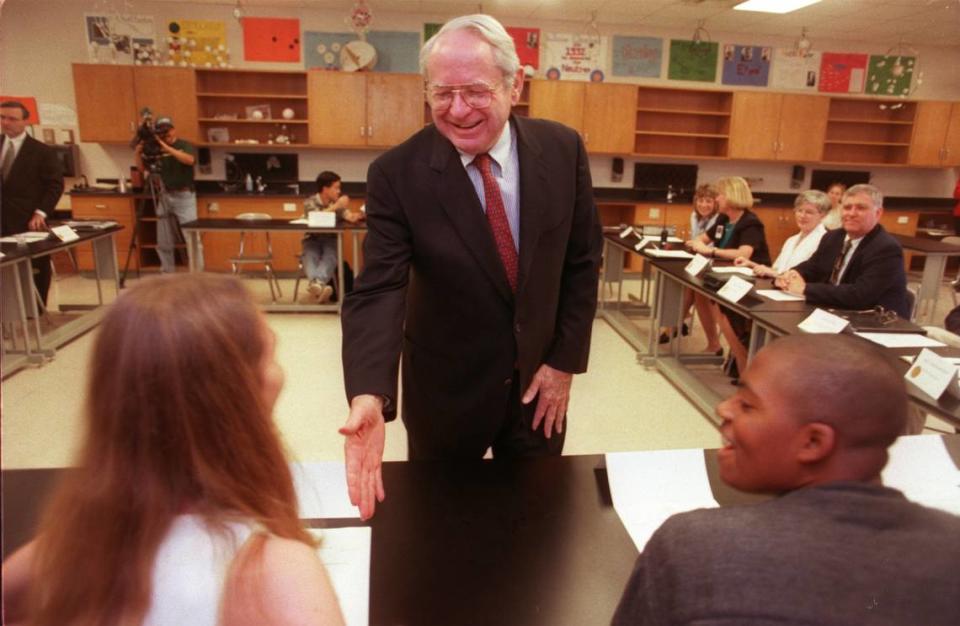

Faircloth spent a term in Washington engaged in his signature issue, “workfare,” or requiring people on welfare to also have jobs. Faircloth took a tough stance on welfare. He was one of the main Senate proponents of cutting off benefits to unwed mothers under 21 and denying additional benefits to welfare recipients who had more children. Those provisions did not make it into the final law.

The changed law President Bill Clinton signed was the work of many people, but Faircloth counted the 1996 welfare reform as the greatest accomplishment of his term, said Peter Hans, who was Faircloth’s senior policy adviser.

“In terms of lasting impact on the country, that’s probably the greatest one,” Hans told the N&O for a news obituary prepared before his death.

Faircloth earned a reputation as an aggressive questioner on the Senate Whitewater Committee, one who wanted to subpoena then-First Lady Hillary Clinton. Clinton counted Faircloth as part of the “vast right-wing conspiracy” against her and her husband.

Conflict with Marion Barry

And as chairman of the Senate subcommittee on the District of Columbia’s budget, his proposal to give financial control of D.C. functions to an outside board inflamed a contentious relationship between Congress, D.C. Mayor Marion Barry and the city council.

“My ability to run a city is exactly that of Mayor Barry’s: None at all,” said Faircloth, quoted in a 1998 Washington Post article.

The conflict inspired a protest at Faircloth’s Senate office, Washington rallies and a bus trip that brought hundreds of demonstrators to Faircloth’s Sampson County farm.

Barry rejoiced when Faircloth lost his bid for a second term to Democrat John Edwards in 1998.

Faircloth’s position made him a target of ridicule and loathing in the city, but his aides said that he should get credit for helping craft a policy that helped rejuvenate the nation’s capital.

Credit should be shared among a lot of people, Hans said, but Faircloth took on a thankless task and provided a valuable service to the city and the rest of the nation.

From working with governors to Highway Commission

Faircloth got his start in politics before he could vote, helping W. Kerr Scott win the 1948 governor’s race. Four years later he helped Scott in his winning U.S. Senate campaign.

He worked on the campaigns for governor of Sanford in 1960, Robert Scott in 1968 and Jim Hunt in 1976. Faircloth was rewarded with government appointments — a seat on the state Highway Commission to start, then leadership of that commission, the precursor to the state Department of Transportation.

In his business life, Faircloth got his start working the family farm, but diversified to including car dealerships, a real estate portfolio of shopping centers and a construction business. He was commerce secretary under Hunt until he resigned in 1983 to run for governor, one Democrat in a field of six.

Brad Crone, now a political consultant, was deputy press secretary for Faircloth’s campaign.

“He had the most energy of any single person I’ve ever worked for,” Crone said. “He worked hard, and he played hard, too.”

Faircloth attended college for only a short time but was a big reader. He reveled in history, including business histories.

Crone said that as the campaign prepared to hit the road, Faircloth bought him a volume of North Carolina history from a Chapel Hill bookstore and told him to read a chapter each night they were on the road.

“I got my master’s degree in North Carolina history from Lauch Faircloth University,” Crone said.

Surviving a plane crash

Crone credits Faircloth for saving his life when the two men, along with a captain and a co-pilot, crashed into Lake James as they started a night flight from Marion in mountainous McDowell County to Raleigh.

The plane caught fire in the crash. Faircloth forced open a wrecked hatch, and the men escaped.

“In another 15-30 seconds, we would have choked on the smoke,” Crone said. “I’ve been loyal to the man because he saved my life.”

All survived the crash, but Faircloth was burned by gasoline that had seeped into the lake and caught fire.

Known for his quick if sometimes off-color wit, Faircloth joked that Crone dove through the hatch like one of the “Great Wallendas.”

Though Faircloth didn’t make it to the primary runoff in that governor’s race, he maintained a friendship with the party nominee, Rufus Edmisten. Edmisten was state attorney general when Faircloth was running the commerce department and they shared jokes during candidate forums.

“We were kindred spirits,” Edmisten said.

Edmisten lost the governor’s race to Jim Martin but was later elected secretary of state. After he resigned from that office after reports of improprieties, he turned to Faircloth — now a U.S. senator — for help.

Edmisten met Faircloth in Washington, where the senator made a call that helped Edmisten get a job as a lobbyist.

“He came to my aid when I was down in the valley of despair,” Edmisten said. “That says a lot about a man.”

Faircloth is survived by his daughter, stepson and two grandchildren.

Staff writer Dan Kane contributed to this report.