As journalism programs across Canada face low enrolment, schools hit pause to modernize

Brazilian international student Fernando Bossoes came to Canada to study journalism. Now in his second year at Humber College's Bachelor of Journalism program, he chose the Toronto polytechnic partly because the journalism programs offered back home were too "old school" for his liking.

But just a few months after Bossoes began his studies, Humber announced that it would be pausing new admissions to the program in 2023. And while his cohort started with seven students, that number has dwindled to four — including an exchange student who will be leaving next year, he said — after several people dropped out.

"Of course, I was expecting a small class because journalism is not an industry that people are really interested in right now," said Bossoes, 19.

Humber College is one of six Canadian schools where a journalism program has been shut down or paused in the last year due to low enrolment. The list includes Loyalist College, Wilfrid Laurier University and Mohawk College in Ontario, plus the South Alberta Institute of Technology and the University of Regina.

While some of the programs are folding indefinitely, others are being temporarily suspended, with administrators citing a need to reinvent and refresh the curriculum to meet the needs of the digital age.

From declining trust and interest in news media to a challenging job market that has impacted local newspapers and legacy newsrooms alike, experts say that schools need to update their programs to attract prospective journalists.

"We all know that a lot of people today — young people — they don't watch the news, they don't turn [on] the TV to watch the news," said Bossoes. "They go on social media, they go on TikTok, they go on Instagram to see what's happening in the world."

More emphasis on independent journalism

Those news habits were reflected in the 2023 Reuters Institute Digital News Report, which found that — while the public is uneasy about the spread of misinformation and algorithms — a reliance on video platforms like TikTok has continued to grow, especially among those under 25.

"While mainstream journalists often lead conversations around news in Twitter and Facebook, they struggle to get attention on newer networks like Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok, where personalities, influencers and ordinary people are often more prominent, even when it comes to conversations around news," the report said.

LISTEN | CBC education producer Nazima Walji on J-school troubles:

Journalism schools have been wrestling with a changing news media landscape for years in tandem with the rise of misinformation in online spaces. Guillermo Acosta, the dean of the faculty of media and creative arts at Humber College, said that the profession has been affected by "a lot of noise."

Small cohorts like the one Bossoes is part of don't lend themselves to debate or to field work, said Acosta. With its Bachelor of Journalism degree on pause, the school is consulting with students, faculty and other players to decide what the future of the program will be.

"There's evidence of more of an interest in a much more entrepreneurial way to do journalism, more independent journalism," he said. "So we're trying to understand what that means and how we can embed that in the education or experience."

Mohawk College, which announced in June that it would suspend its three-year journalism diploma, did so in part to revamp its course offerings, which several students previously told CBC News needed to be modernized. The school similarly suspended its Broadcast-Radio program for a few years, eventually reintroducing it as the Broadcast-Radio Creative Content program.

But it isn't all bad news — some of Canada's largest journalism schools continue to see healthy enrolment.

A spokesperson for Concordia University told CBC News that its J-school programs are growing and that the school recently introduced a science journalism minor. Graduate programs have increased by 45 per cent since 2016, while enrolment remains steadily full at the undergraduate level.

Ravindra Mohabeer, chair of the School of Journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University, wrote in a response to CBC News that the school's enrolment has increased year over year for the last three years, from 150 first-year students in 2021 to 170 students this year before attrition.

He said the school is always revising its curriculum, and that there are no plans to pause its Bachelor of Journalism or Master of Journalism programs.

A statement from Carleton University did not share enrolment numbers, but said that the journalism school is "in a constant state of renewal to meet the needs of today's modern journalist."

Students make their way around the Toronto Metropolitan University campus in Toronto on Wednesday, April 26, 2023. The university's School of Journalism has seen a year-over-year increase in enrolment, according to its chair Ravindra Mohabeer. (Nathan Denette/The Canadian Press)

Paradigm shift needed, says UBC prof

Not everyone agrees what those needs are. While some of the paused programs said they are updating to incorporate more multimedia courses, one Canadian professor suggests that tech isn't the issue.

Instead, there needs to be a paradigm shift in "how we are approaching journalism as a field and what kind of journalists [we] want to train for the future of Canada," said Saranaz Barforoush, an assistant professor of teaching at the University of British Columbia's School of Journalism, Writing and Media.

LISTEN | A discussion of how Canadian media represents racialized people:

That might mean introducing more community-focused courses, emphasizing solutions-based journalism, or introducing courses that teach students how to cover racism or marginalized communities.

Barforoush said that "if more students and more people see themselves on the news — people that look like them, that represent them, that sound like them — then there may be a little bit more enthusiasm to get into the field and try to invoke positive change."

Saranaz Barforoush, an assistant professor of teaching at the University of British Columbia's School of Journalism, Writing and Media, said journalism schools can introduce more community-focused courses to appeal to a new generation of students. (UBC School of Journalism)

A 'bulwark' against misinformation

That most of the journalism program closures are happening in mid-sized or small markets could further erode the health of local journalism, Barforoush said.

"If all the journalism schools and trainees are going to focus on big cities then that usually means that the people that come in are either from those big cities or those who can afford to live in these big cities," she said.

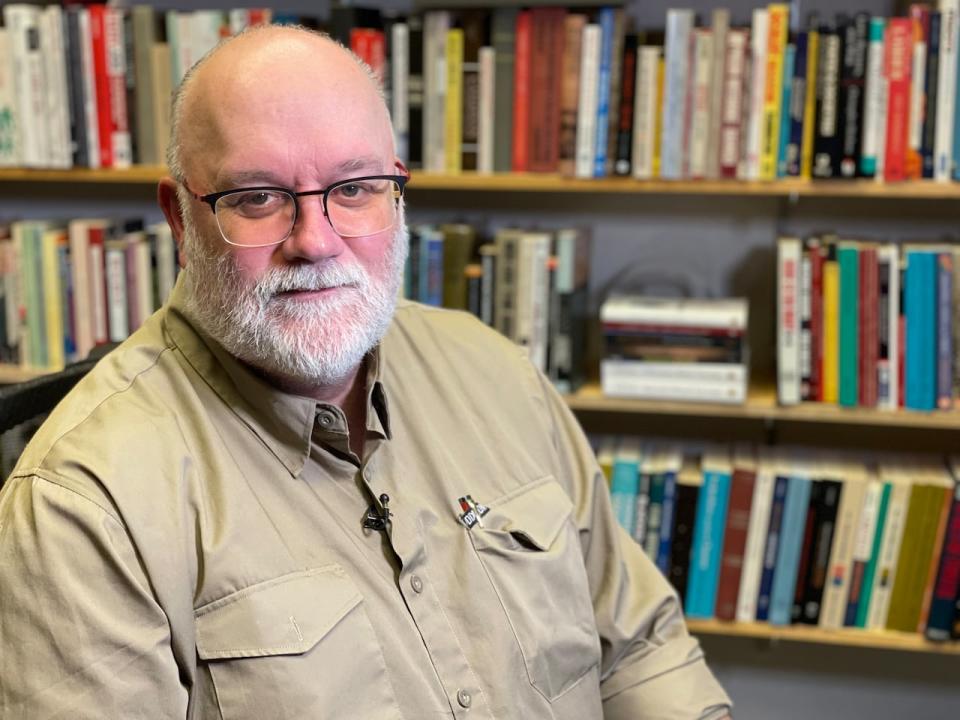

Tom McIntosh, an associate dean of arts at the University of Regina, said that well-trained journalists are a bulwark against misinformation. The university's journalism school recently paused admissions to update its program for the digital age. (Nazima Walji/CBC)

The University of Regina recently paused admissions to its journalism school. Tom McIntosh, an associate dean of arts, said the program's graduates are an important part of the city and province's media ecosystem, and that their first jobs are often in local Saskatchewan media.

Declining enrolment in the graduate program, coupled with issues around "the capacity of faculty to deliver the program as it had been structured" contributed to the decision to pause it, McIntosh said. In the meantime, the school is developing an undergraduate journalism program that could begin accepting students next fall.

"It was important that we give … the school a chance to reinvent itself so that we can continue to be a source of well-trained new journalists for the Saskatchewan market," he explained.

"We are in an ongoing battle over misinformation that is out there, whether it's on social media or various other websites and the like," said McIntosh. "A bulwark against that [is] a continual creation of well-trained professional journalists."