Lost to history, Saint John's silent movie is barely a memory a century later

When Ernest Shipman arrived in Saint John in late summer of 1922, he came with a reputation as Canada's most successful movie producer.

The Toronto-born entrepreneur had been in the entertainment and publicity business since his early 20s.

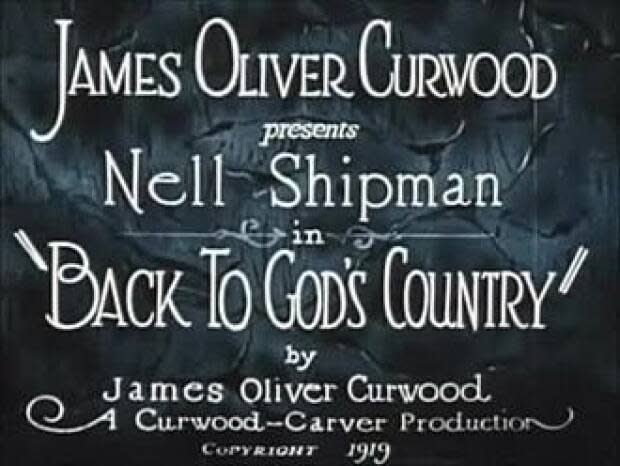

In his 25 years or so in the business, he had produced Canada's most successful silent movie, 1919's Back to God's Country.

Filmed in Calgary, and starring his wife and screenwriter Nell Shipman it was made for $67,000, and grossed more than $1.5 million.

Shipman's local investors quadrupled their money, and he parlayed that success into projects across the country over the next few years.

Mark Blagrave, a writer and retired university professor, based his novel, Silver Salts, on that first effort to make a movie in Saint John.

"Shipman, after his success with Back to God's Country, which still appears, I think, on Turner Classic Movies every now and again … sort of made his way across Canada dropping into towns and kind of betting on people's loyalty to local writers," Blagrave said in an interview from his home in St. Andrews.

But there was another side to "Ten Percent Ernie," who earned the nickname for his insistence that he receive 10 per cent of everything his employees earned.

A hard drinker and a smooth talker, Shipman's investors didn't always see the money they were owed.

"And so he showed up in Ottawa and started an Ottawa film company to do a Ralph Connor novel and, you know, took a group of actors into town and made a film called Cameron with the Royal Mounted and then just kept moving east, probably ahead of his creditors."

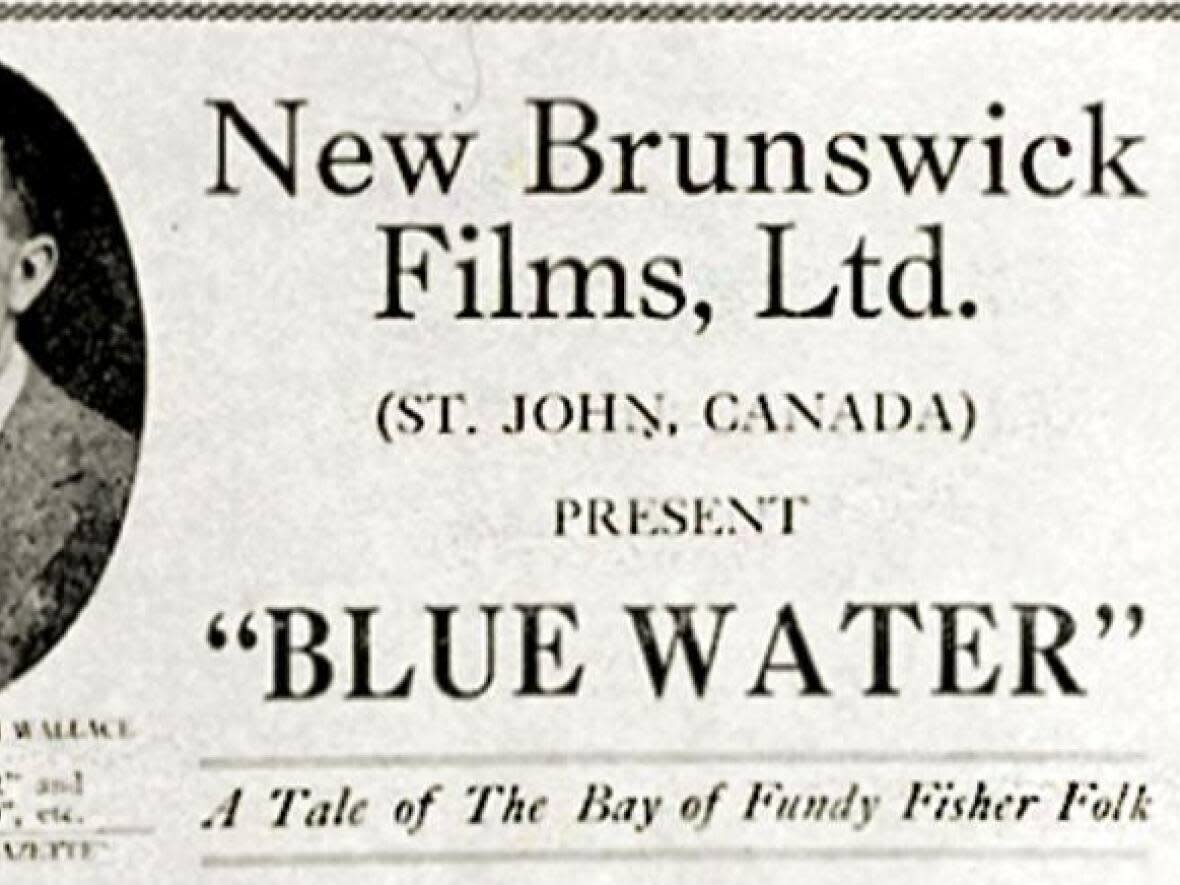

In Saint John, his local investors in a company called New Brunswick Films Ltd. included New Brunswick Premier and Saint John MLA Walter Edward Foster.

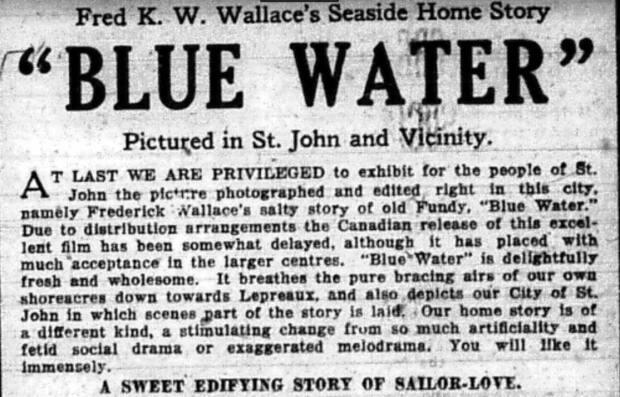

But Blue Water, the story of a Bay of Fundy fisherman who battles alcoholism and storms at sea to find true love, would be Shipman's undoing.

Cast and crew

It didn't start out that way.

First, Shipman knew he had a good story.

The novel by journalist and writer F.W. Wallace was a popular book in its own right.

Brook Taylor, a history professor at Mount St. Vincent University and author of the book A Camera on the Banks: Frederick William Wallace and the Fishermen of Nova Scotia, said Wallace wrote from his personal experience onboard the sailing vessels of the Bay of Fundy.

"After he had been out to sea in the schooners, he could begin to write novels like Blue Water that are based on his first hand experience. He had been out there, he had done these things."

Shipman also had a good cast and crew, including Montreal-born actress Norma Shearer, who was cast as the love interest.

Shearer had a number of motion pictures on her resumé already and was just about a year away from signing with MGM.

She joined American actors Pierre Gendron and Jane Thomas, and director David Hartford, who had been at the helm for many of Shipman's films, including the movie that made his reputation.

Blagrave said there was a fair amount of excitement in the province about the prospect of the filming.

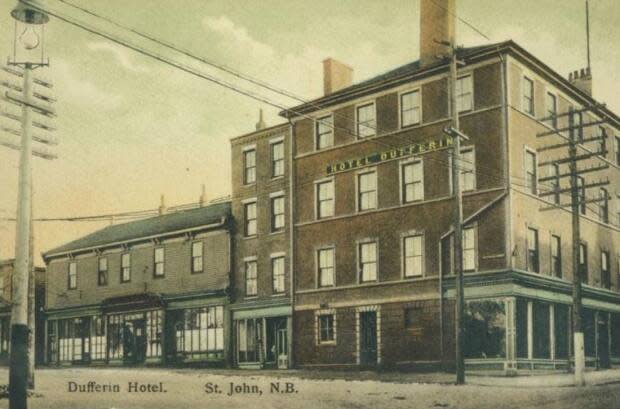

"I think when the auditions for extra parts — because the stars were all imported but the extra roles were locals — there must have been enormous excitement to go to the Dufferin Hotel, which stood where the Admiral Beatty is now, and to be auditioned as an extra in a movie with some names from the U.S.," he said.

"Norma Shearer wasn't well known, but some of the other people, you know, had been in films and potentially people had seen them already on the screen of the Imperial Theatre."

"So yeah, it must have been pretty damn exciting."

The newly-formed New Brunswick Films also sold 990 shares to investors at $100 a piece, selling out in a month.

Filming started in October, using Saint John for city scenes and Chance Harbour for the seafaring scenes. Interior shots were done in a makeshift studio at the city's St. Andrews rink, which was located at 219 Charlotte Street.

Blagrave said the company spent about $60,000 on the production in Saint John, but soon ran into unexpected problems.

It seems no one in the production team had considered that immersing actors in the waters of the Bay of Fundy in October wasn't the best idea.

It proved impossible to properly shoot the sea sequences, especially as colder weather set in, and the production stalled.

Behind schedule, and with a good portion of the money spent, the crew quietly packed up and headed to Florida in early November to finish shooting in the Tampa area, which must have created a continuity nightmare for editing.

It would be almost 18 months before the film finally made an appearance in completed form.

On April 16, 1924, Blue Water had its premiere at the Imperial Theatre in Saint John.

It had four screenings over two days, and newspaper stories of the day said it was well attended.

The Saint John Globe's short review was more kind than glowing.

"The Chance [Harbour] pictures are sweet and home-ly, the storm scenes thrilling and the acting of the large company wholly acceptable," it said.

"For a first attempt at putting on a [Saint] John picture, Blue Water is by no means unsatisfactory."

Blagrave said it's not surprising the newspaper was gentle in its assessment.

"I suspect that some of the people working at the newspaper had a little bit of money in N.B. Films and were still hoping two years later to see even just some of it back."

Poor reception

A review in a U.S. publication was far more damning.

Appearing in Screen Opinions, a publication intended for movie theatre owners, Blue Water received a 25 per cent rating.

"Poor enough to drive patrons from your theatre," it said. "An attempt to make a picture with a moral ruined through incompetent adaptation and direction. The picture is carelessly edited, and with the exception of some storm scenes at sea it has little to offer by way of real entertainment."

It appears some theatres in the U.S. did screen the film in New Jersey and New York.

A copy of the five-reeler, which probably ran about 55 minutes, was placed in a film vault at the Stone Film Library in New York City, and there are some references to suggest it was played at a New York department store in 1936 as a novelty to attract crowds.

But that is likely the last time it ever saw the light of day.

The Aftermath

Clearly, no one who bought shares in the company ever made any money off it, and Blagrave said they undoubtedly harboured ill-feelings toward Shipman.

"I would think there would have been a lot of people in Saint John who would have liked to at least burn him in effigy, if they couldn't get their hands on the real thing."

That likely included New Brunswick Premier Walter Edward Foster, who resigned his post in February of 1923 to focus on fixing his personal finances.

Shipman gave up on his plan to head to Halifax to film another F.W. Wallace novel.

He never made another movie and died in obscurity in New York in 1931 from cirrhosis of the liver.

Brook Taylor said Wallace was apparently "quite chuffed" about the movie and happy it closely followed his novel.

Another of his novels was made into a movie in 1927.

Wallace continued to write, and his 1924 book Wooden Ships and Iron Men is considered one of the great histories of the Age of Sail.

Shearer was signed as a contract player by Louis B. Mayer in 1923 and would become a big star

She made the transition from silent movies to talkies with MGM, won a Best Actress Oscar in 1930 and became one half of a Hollywood power couple when she married MGM head of production Irving Thalberg.

Shearer retired from the film business in 1942.

Blue Water is now considered a lost film, and the only reason there's any interest in it these days is because it's an early movie featuring Shearer.

But, Blagrave, who did spend some time seeking out a print of the film, said if a copy ever did surface, it would be wonderful to see how Saint John was featured in the film.

"It would have been absolutely amazing … as far as I can gather, they did a lot of shooting in the uptown, making it stand in for Boston."

But Blagrave said, with so few prints made, and given the volatility of the old nitrate film stock, it's unlikely anyone will ever see even a snippet of the lost film.