Metro Vancouver's snowpack looks good this year, but future water supply still a question mark

For over 80 years, Metro Vancouver field hydrologists have used the same technology and techniques to estimate how much snow — or in effect, drinking water — is stored in our three mountain reservoirs.

It's not overly complicated: trek up a mountain with some heavy measuring equipment and take multiple manual observations of the snowpack across various sites in the watershed.

With a bit of math, you can obtain a pretty good estimate of how much water is contained within all that snow — an early indicator of how much drinking water Metro Vancouver will have available to use during the dry summer months ahead.

But according to Metro Vancouver field hydrologist Peter Marshall, the margin for error in these manual measurements could be as high as 20 to 40 per cent.

"It's time consuming and it involves a lot of resources," Marshall said.

One solution? Use remote sensing technology.

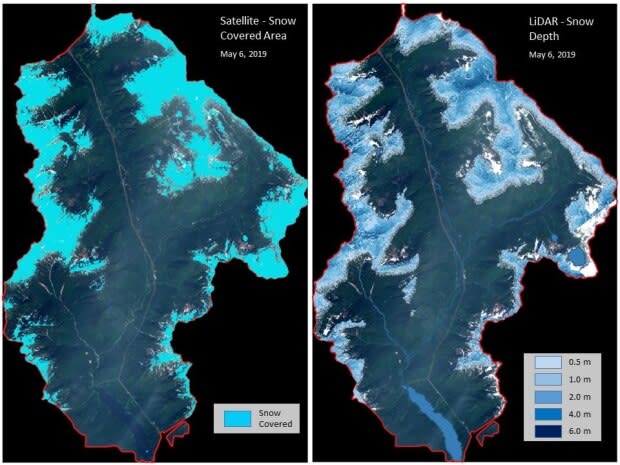

One of the new tools Metro Vancouver will be employing this year is something called Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR).

"That's using aircraft or drones to basically send a signal of light down to the earth surface, which then reflects back," he said.

These signals are sent over Metro Vancouver's watersheds twice: once in the summer when the mountains are snow-free, and then again in the winter or spring when they are snow-covered.

Comparing the two results gives you a measurement of snow depth across the entire watershed.

When combined with manual observations taken by Marshall and his team, LiDAR will provide a much more accurate representation of how much — or how little — drinking water the region can expect to have for the drier and warmer months of the year.

An uncertain future for Metro Vancouver's water supply

While this technology provides a clearer picture of Metro Vancouver's water supply for the season ahead, it does not protect us from a rapidly changing climate — one where a healthy mountain snowpack is far from guaranteed.

"Our climate is clearly showing that the early spring is warming up much faster than the rest of the year, which means the snow is going to melt earlier," says University of British Columbia professor emeritus Hans Schreier.

It's a precarious situation to be in: if our snowpacks melt earlier, it will be nearly impossible to replenish our reservoirs during the dry summer months, when average precipitation across the region is at its lowest — and trending even lower each year.

"In the last 17 to 18 years we have had about a 20 per cent reduction in precipitation between May and August," says Shreier.

And yet, Metro Vancouver uses a staggering amount of water during this time.

"When you think of the water use in our region in midsummer we use on average about one and a half billion litres of water per day," says Marshall.

Such consumption is simply not sustainable in the years ahead, and points to one solution: conservation.

"If we can cut that down by almost half a billion litres of water, perhaps, that's a major savings," said Marshall.

The City of Vancouver emphasizes that minimizing your outdoor water use is the single biggest thing you can do in the summer to save our treated drinking water for where it's needed most: drinking, cooking and cleaning.

And despite our reputation as being the "wet coast," assuming we'll always have enough water in Metro Vancouver is short-sighted.

"We're really blessed with an abundance of water," said Marshall. "We often see a lot of snow in our local mountains, but it's important to think more long term."

And while preliminary observations of our region's snowpacks in 2020 are on track with historical normals, there's simply no guarantee what the next season will bring.