How this NC author writes authentic stories about race for kids and their families

Alicia D. Williams never set out to be a children’s author.

In fact, the award-winning Charlotte writer laughs when asked if success was part of the plan. “I wish I was one of those people who said all my life, I knew what I wanted to be, but I didn’t,” she said. “I loved storytelling and drama. But learning that how to best articulate and express myself was through my book characters came later.”

Later has arrived.

WIlliams’ first book, for middle grades, tackled themes of family and Black identity, won awards and a rave in The New York Times in 2019.

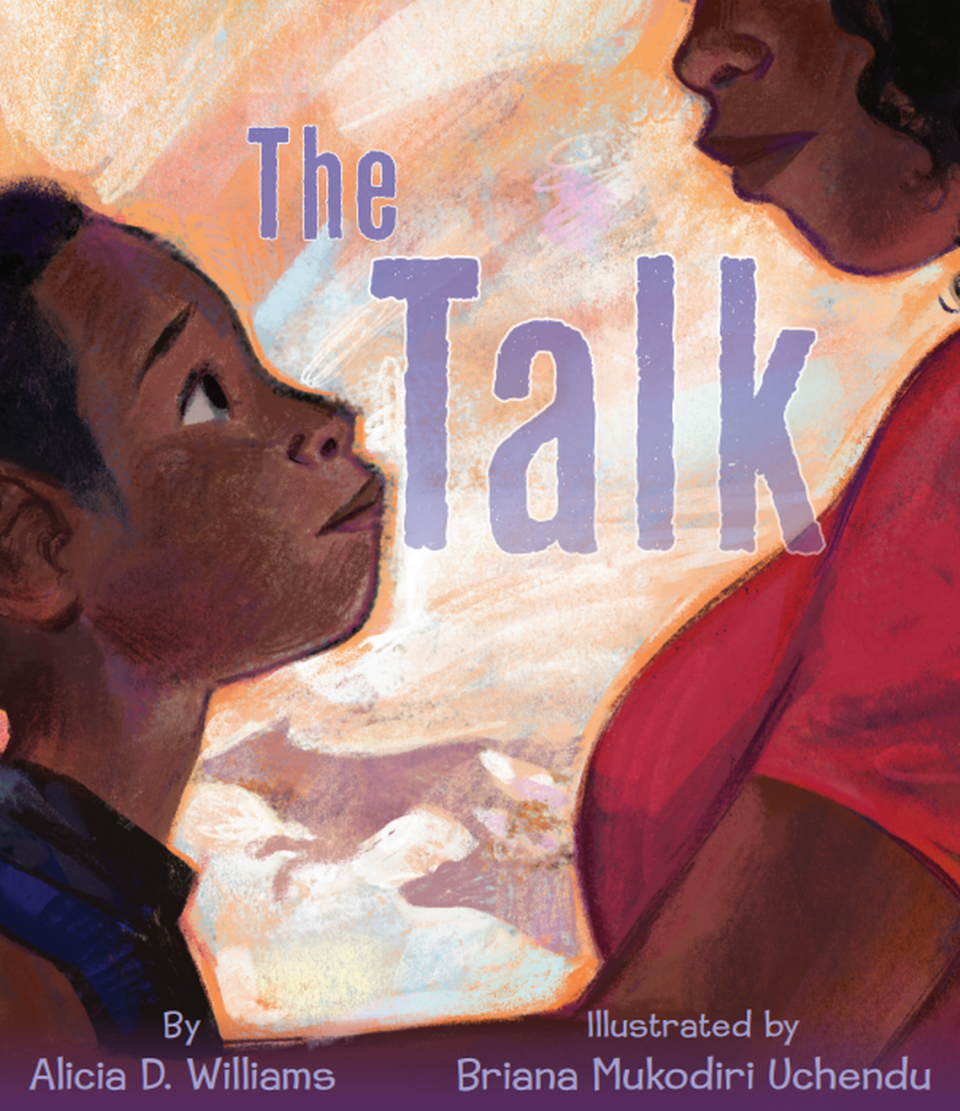

Her latest book came out last fall. “The Talk” covers the all-too-familiar conversation Black and brown parents have with their kids to keep them safe. It’s a book aimed at children ages 4 to 8, and also has won awards for Williams.

Williams wrote “The Talk” after inadvertently watching the Ahmaud Arbery video, where a 25-year-old Black man who was jogging in Georgia was killed by three white men in a racially motivated crime.

“I knew this was weighing on my mind,” she said.

“Anytime I approach a story, it’s something I’m trying to grapple with, something I’m trying to understand, something I’m trying to work out — to see if there is a solution to get closer to understanding the world in which we live in.

“I feel like a sense of responsibility on how I serve that message in there,” she added. “That is not something that I’m giving it to readers, but for them to come to the conclusions on their own.”

Finding her purpose

When work brought Williams from New York to Charlotte, the American Musical and Dramatic Academy alum thought that she had left a career in the creative arts behind. Williams first came to Charlotte through her job as a flight attendant for American Airlines and then took a job working for Bank of America.

But she missed the arts.

A move into education, which allowed her to focus on arts integration, proved to be a good fit.

And enrolling in graduate school at Hamline University in Saint Paul, Minnesota, brought her closer to her purpose. It was during that time that Williams composed her first full length work, a novel for kids 9 and older that addresses racism and colorism head on.

Encouraged by a professor, Williams sent the manuscript off and quickly secured an agent. That first book, “Genesis Begins Again,” focused on a young teen who hates her dark black skin and hair, prays for beauty and hopes to win a singing contest at school to help her troubled family.

The New York Times compared to the Toni Morrison classic “The Bluest Eye” and it received Newbery and Kirkus Prize honors.

Why she writes

For many families, “the talk” that Williams’ book references is that moment when the reality of growing up Black or brown in America is laid out clearly to children.

In the book, protagonist Jay enjoys a life of family and friends in concert with his white counterparts.

He loves to run unfettered through the neighborhood with his friends. He feels safe when enveloped in the hood of his father’s college sweatshirt and doesn’t know why wearing it could bring him danger. He jokes when his mother laments his loss of boyhood and increasing height.

But as Jay inches toward adolescence, his family knows that racism means he will be seen as a threat —and that what he wears and how he moves can mean the difference between life and death.

The book’s illustrations (by artist Briana Mukodiri Uchendu) reinforce these realities. One, featuring a blurry television screen with a CNN story on police brutality still legible, is especially resonant.

Literature for children and young adults has long come under scrutiny by institutions and individuals claiming they are protecting impressionable young minds from questionable or dangerous content.

Williams is emphatic in her response to the question of whether literary content should be censored for young readers. Tough topics like poverty, bullying, trauma, racism — these are experiences that kids are living through.

“All these things happen at a young age, but we want to say our children aren’t ready? I write because our children are ready,” she said. “I know I write in a way that’s gentle enough, compassionate enough, and authentic enough to reach children at their level.”

Censorship concerns

Last year, a report from PEN America found that 5,049 schools in 32 states had banned more than 1,648 titles. Also last year, the American Library Association said the number of attempts to ban or restrict library resources in schools, universities and public libraries exceeded the record counts of 2021.

This trend unsettles Williams, who believes that whether books are non-fiction or fiction, they are essential sustenance to young readers and their caregivers.

“When people choose to ban books, you know there’s a reason you don’t want these books to be read. These books give hope, they give answers, they give empathy, they break down fear,” she said. “And the walls that we build ourselves around, we give understanding. They are literal road maps to freedom.”

Though Williams has worn many professional and creative hats throughout her career, she says that writing and teaching through her books is her true calling. It’s how she hopes to leave the world a better place.

She emphasizes the significance that words can provide, arguing that children need stories to inspire hope or change, or make them want to take risks or action.

“Through my pen or my keyboard, that’s how I get out to support whatever we’re going through in this time of history,” she said.

And much like Morrison, the literary ancestor to whom her work has been compared, Williams believes in the power of language. It builds bridges between communities, fostering greater understanding and empathy.

More arts coverage

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up here for our free “Inside Charlotte Arts” newsletter: charlotteobserver.com/newsletters. And you can join our Facebook group, “Inside Charlotte Arts,” by going here: facebook.com/groups/insidecharlottearts.