NC bill advances to force Chemours, others to pay for harm done to drinking water by PFAS

A renewed legislative effort to force Chemours and other forever chemical manufacturers to pay for drinking water contamination cleared its first hurdle on Tuesday.

The House Environment Committee voted unanimously for House Bill 864, legislation sponsored by a pair of Wilmington-area Republicans who failed to win support for a similar bill two years ago.

Under the legislation, the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality would be able to order manufacturers of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances to pay for water utility upgrades if it can be proven that their discharge is resulting in levels higher than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s recently enacted drinking water standards that cover five individual compounds and a chemical mixture.

“This legislation is about protecting us to have clean drinking water, and also to protect the ratepayers for the utilities not to have to foot the bill for the humongous expense to buy all this equipment to make the water be able to be safe to drink,” said Rep. Ted Davis, a New Hanover County Republican.

Under the legislation, Chemours would have to pay any costs downstream utilities incurred since Jan. 1, 2017, to protect themselves from elevated levels of PFAS coming from the factory. The public learned of PFAS contamination in the drinking water of Wilmington and other nearby communities that draw from the Cape Fear River in June 2017, when the Wilmington StarNews reported on findings from researchers at N.C. State University.

PFAS have been linked to a wide array of health effects, with specifics varying depending on the compound. Animal studies found that the chemical known as GenX, for example, can increase the weight of livers and kidneys, suppress immune system antibodies and has some links to liver and pancreatic cancer, according to the EPA.

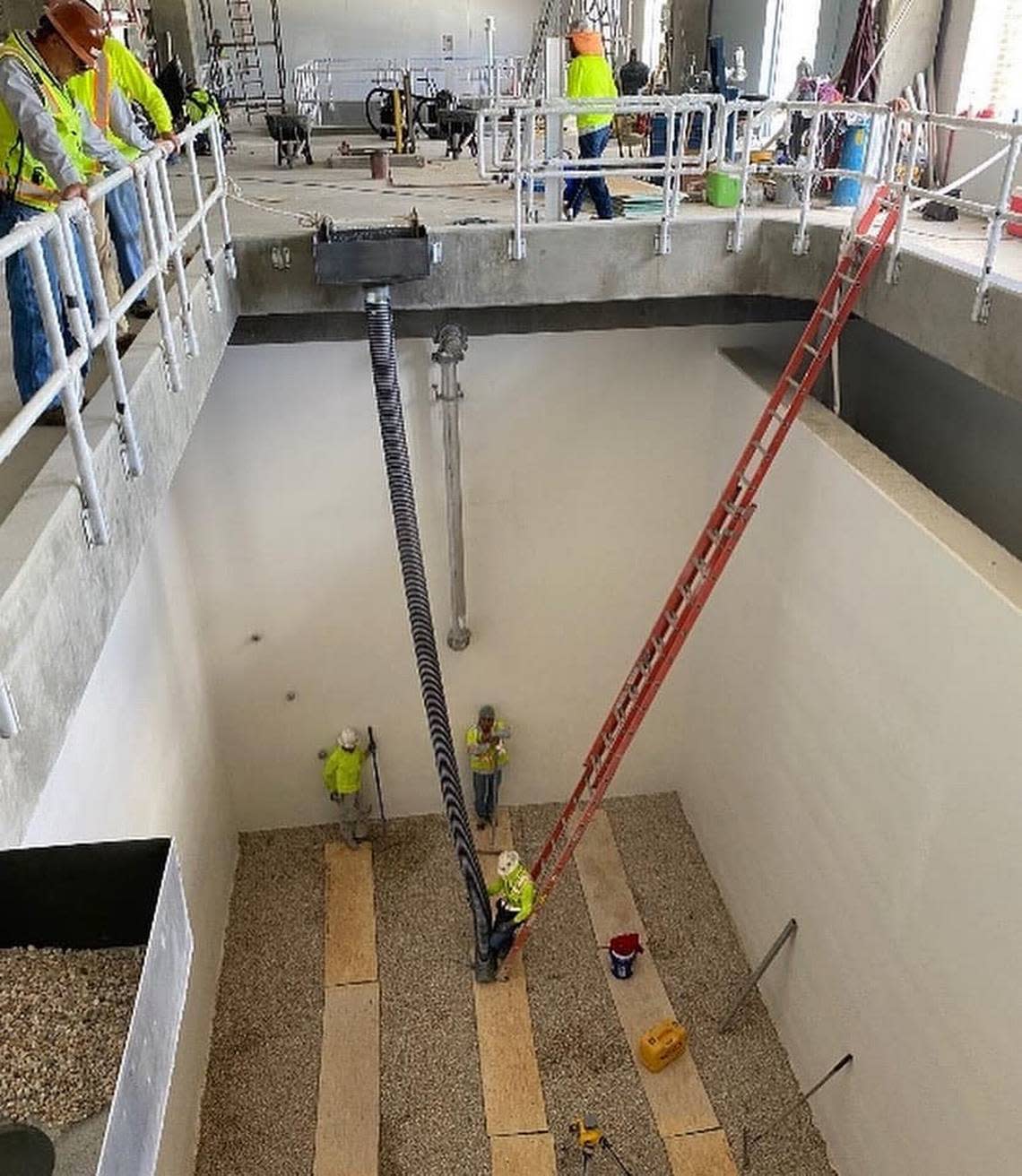

To protect its drinking water, the Wilmington-area Cape Fear Public Utility Authority installed eight new granular activated carbon filters to capture forever chemicals coming downstream. The public utility has spent nearly $75 million in total, including $54 million to build the new filters and ongoing $5 million costs to swap out the carbon in the filters.

“All these millions of dollars are coming from the rates CFPUA customers pay, not from those who are financially benefiting from the manufacture and sale of these PFAS chemicals,” Beth Eckert, CFPUA’s deputy executive director of environmental management and sustainability, told the committee.

Neighboring Brunswick County has embarked on a $170 million project to build a reverse osmosis plant that can remove the chemicals from drinking water drawn from the Cape Fear River. Once that plant becomes operational, likely next year, it will cost $2.9 million to operate annually, said John Nichols, the director of Brunswick County Public Utilities.

So far, the average water bill in the county has increased from about $25 to about $35, Nichols added, with rates likely to continue rising.

“In the regulatory world, there is a polluter-pays principle and so that is not currently being applied. We think it is important for that to be applied so that the cost burden is on the appropriate individuals,” Nichols said.

Responsibility for PFAS contamination

Davis was careful to make clear that only companies that manufacture PFAS would need to pay for pollution, under the terms of the bill. Companies that use PFAS to make a given product would not be subject to it, Davis said.

Beyond that, a PFAS manufacturer’s discharge would need to make its way into a public drinking water source at levels higher than the drinking water maximum contaminant levels set by the Environmental Protection Agency earlier this year.

As in 2022, members of the business community said they had concerns about the bill.

A Chemours representative asked that the bill not advance out of committee, saying the company built a thermal oxidizer to control PFAS-laden emissions and built a seven-story underground barrier wall and treatment system to control the chemicals in groundwater.

“This bill really targets my company and the 560 colleagues of mine who work at the Fayetteville Works plant in Fayetteville,” said Jeff Fritz, Chemours’ state government affairs lead.

The bill could have a chilling effect on efforts to grow the state’s manufacturing base, warned Lu-Ann Perryman, a lobbyist for the N.C. Manufacturers Alliance. Perryman was one of several who questioned the appropriateness of legislation forcing companies to bear costs borne by utilities since 2017.

“It applies the 2024 regulations to incidents that occurred as far back as 2017, irrespective of when (a maximum contaminant level) was established by the EPA,” Perryman said

Davis, the Wilmington-area Republican, said the bill is not intended to specifically affect Chemours, even if it certainly would apply to them. And the 2017 date is simply leveling the playing field, he said.

“This bill is targeted at anyone — anyone — in this state that makes this stuff from scratch. Chemours happens to do that, but I will say they knew very well what they were doing and they didn’t do any of this remediation efforts until they got caught in 2017. That’s why we have that date in this bill,” Davis said.

Previous effort failed

A similar bill seemed poised to move through House committees in 2022, which would have allowed it to come up for a vote on the House floor.

But representatives from powerful business groups — including the N.C. Chamber, N.C. Manufacturers Alliance and the American Chemistry Council — all argued that House Bill 1095 was anti-business and would threaten growth in the state, The News & Observer reported.

The arguments from Wilmington-area utilities and Chemours were also similar to those heard Wednesday.

But the outcome was different. There was no vote in the 2022 committee. HB 1095 was ultimately withdrawn and not voted on that session..

The new bill, House Bill 864, will next be heard in the House Appropriations Committee. If it is approved there, it goes to House Rules. From there, it would be voted on by the full House before moving over to the Senate.

This story was produced with financial support from the Hartfield Foundation and Green South Foundation, in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners, as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The N&O maintains full editorial control of the work. If you would like to help support local journalism, please consider signing up for a digital subscription, which you can do here.