The Queen's death may cause many old Commonwealth ties to unravel

The realms of the British monarch have shrunk since a quarter of the Earth's land mass was coloured imperial pink, and a quarter of the world's people were subjects of George V, King of the United Kingdom and British Dominions and Emperor of India.

The first crack in the facade appeared one hundred years ago, when Britain ratified a peace treaty to end the guerrilla war that had made Crown rule unenforceable in much of Ireland.

Over the subsequent quarter century, that crack would spread to other colonies — first in the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East, then in Africa and the Caribbean — weakening the edifice until the shocks of the Second World War caused imperial collapse.

Military defeats from Burma to Hong Kong had weakened British prestige and the undisputed top dog in the post-war world — the United States — saw the British and French empires as liabilities in the new ideological struggle with the Soviet Union.

A (relatively) smooth transition

Avoiding the violent disintegration of the French and Portuguese empires, Queen Elizabeth II navigated a surprisingly smooth transition from Empire to Commonwealth, a voluntary association that remained open even to those former colonies — the majority of them — that chose to become republics (or to restore their own royal lineages, such as Swaziland/Eswatini and Lesotho).

Those who dropped the monarchy included the "jewel in the crown," India — which achieved independence in 1947 and declared itself a republic two years later — and successor states Pakistan and Bangladesh. It also included all former British colonies in Africa, which achieved independence between 1957 and 1968.

As early as 50 years ago, the Queen was head of state in only about a quarter of Britain's newly independent colonies — including Canada, Australia and New Zealand, the former Caribbean colonies from the Bahamas to Belize, and a handful of Pacific nations such as Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

In recent years, the Commonwealth has grown to accept new members who were never even in the British Empire.

Former Belgian colony Rwanda hosted the Commonwealth Heads of Government Summit this year. Former Belgian colony Burundi has applied for membership. Previously suspended countries such as Fiji, Gambia and the Maldives have been readmitted, and some that left (such as Pakistan) or were expelled (such as South Africa) have rejoined. (Zimbabwe left in 2003 and applied to rejoin in 2018.)

Only Britain's oldest colony has persistently refused to take part in the Commonwealth. For some members of the Irish Republican Army, the acceptance of something less than full independence in 1922 was too bitter a pill to swallow. The new Irish Free State saw a harsh civil war between its former liberators over whether to take the only peace deal on offer, or to hold out for more.

The pro-Treaty side carried the day and for 27 years after the War of Independence, the Irish Free State was a dominion like Canada.

But memories of oppression, starvation and exile, culminating in forced partition, left the Irish determined to have nothing to do with their former colonial master. In 1949, Ireland seized on Britain's weakened post-war state to declare a full-fledged republic and permanently leave the Commonwealth.

Republican rumblings in the West Indies

The recent tour of the Caribbean by William and Catherine, then Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, showed how vivid memories of colonialism remain there as well.

First they were forced to cancel a visit in Belize, where local Mayan people opposed their presence.

Then, in Jamaica, Prime Minister Andrew Holness told the couple that his island nation would be "moving on" to "fulfil our true ambitions as an independent, developed, prosperous country."

The Jamaican government has a timeline. It wants to be a republic in time for its next general election in 2025.

Last year, Jamaica said it would formally petition the U.K. government to pay reparations for overseeing the forced transportation of an estimated 600,000 enslaved Africans to sugar and banana plantations on the island.

With nearly three million people, Jamaica is by far the largest of the Caribbean realms. Its departure from the British Crown would mean that four out of five people in former British colonies around the Caribbean would live under a republican system of government.

'Complete the circle of independence'

The British in the nineteenth century went from being the world's biggest slavers to its most ardent abolitionists, and the Royal Navy strived to suppress the African slave trade decades before the U.S., Cuba or Brazil emancipated enslaved people.

But it's also true that the wealth of the Royal Family, and of British cities such as Liverpool, rests partly on the stolen labour of generations of enslaved people — people who were never compensated for what was taken from them, while slaveowners were generously indemnified following abolition.

Plantation slavery in the British Caribbean was replaced with a discriminatory system that effectively limited the franchise to a small, mostly white elite, while the majority continued to face harsh working conditions and even harsher repression if they rebelled.

Still, most of the British Caribbean continued to accept the Queen as head of state following independence. Only Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, and Dominica chose the republican alternative.

Last year, though, a second wave of breakaways seemed to begin when Barbadian PM Mia Mottley led her country away from the British crown at a ceremony attended by the island's favourite daughter, Rihanna.

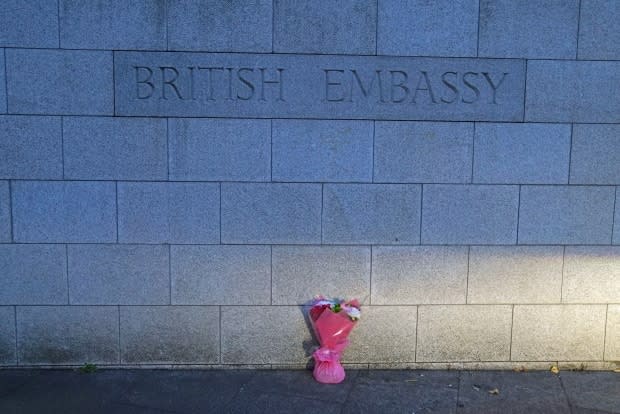

And following the death of the Queen, Antigua and Barbuda's PM Gaston Browne announced his own plans to call a referendum on the monarchy on the same timeline as Jamaica.

"This is not an act of hostility or any difference between Antigua and Barbuda and the monarchy," he said. "But it is the final step to complete that circle of independence, to ensure that we are truly a sovereign nation."

Australia: What's the alternative?

Barbados chose an easy glide-path to a republic by simply proclaiming its old governor general as its new president.

But larger nations — particularly those with federal systems — face more complicated issues. Australia's attempt to leave the monarchy behind in the 1990s foundered on the fact that scrapping one system requires replacing it with another.

From the mid-90s on, polls consistently showed that more Australians favoured dropping the British monarchy.

But the alternative Australian politicians proposed in the 1999 referendum — which included a president chosen by politicians rather than directly by voters — was widely seen as a power grab at the people's expense.

In the end, opponents of a republic won a come-from-behind victory with almost 55 per cent of the vote. Some years later, Labor Party PM Julia Gillard pledged to let the issue lie for the remainder of Queen Elizabeth's life.

With the Queen gone, there may be a new window for Australia's republicans — who responded to her death with a restrained statement.

Former PM Malcolm Turnbull, who led the republican side in the referendum, has long argued that Australians are "Elizabethans" rather than real monarchists — that their affection was focused on the person, not the office.

Some polling suggests that support for a republic in Australia may actually have slipped since the 1990s. (It also shows a wide gender gap — women everywhere are more likely to support monarchy than men.)

But Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is a republican and, after coming to office in May, he appointed Matt Thistlethwaite to the new role of assistant minister for the republic, charged with planning a transition away from the monarchy.

Albanese is one of many Australian Labor politicians who have never forgotten the Crown's role in a 1975 constitutional crisis which saw unelected Governor-General John Kerr dismiss elected Labor Prime Minister Gough Whitlam.

Letters between Buckingham Palace and its Australian viceroy were released in 2020 after a lengthy court battle. They reveal that then-Prince Charles (now Charles III) had discussed with Kerr firing Whitlam months before it happened.

Albanese has said he doesn't plan to make any moves during his first term in office, which ends in 2025. But not all Australian party leaders share his patience.

N.Z. not in a rush

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern was quick to dismiss any speculation that her government was considering such a move.

"I've never sensed the urgency," she said. "There's so many challenges we face. This is a large, significant debate. Don't think it's one that would or should occur quickly."

But she added: "I do believe that is where New Zealand will head in time. I believe it's likely to occur in my lifetime."

New Zealand has traveled a long way since the Queen first visited in 1952 — when Auckland City Council evicted Indigenous Maori from Okahu Bay and burned their homes because it feared they were "a dreadful eyesore" that might mar the Queen's view of the bay.

Today, the Maori Party appears to hold the balance of power, with elections coming no later than January 2024.

Its leader Debbie Ngarewa-Packer has made it clear she is no monarchist.

Canada's frozen Constitution

Of all the Commonwealth realms, the one that is perhaps least likely to drop the British monarchy is Canada — simply because its federal Constitution makes it virtually impossible.

Constitutional expert Philippe Lagassé told CBC News that such a change would require the unanimous consent of "all the provinces and the federal Parliament, and I suspect the Indigenous peoples would want a say too, because they have a direct relationship with the Crown.

"I often say that if you want a Canadian republic, what you should do is go to the United Kingdom and advocate for it there, because they just need an act of Parliament. And if they did it, we would be forced to do something."

Such a scenario is unlikely, but not impossible, said Lagassé.

Where Missis Kwin's crown still shines

There remains one bright spot for the British crown: Papua New Guinea.

While the tour by the Prince and Princess of Wales of the Caribbean was met with protests and even snubs, Princess Anne was conducting a much more successful tour of the Crown's largest possession that is not majority-white.

PNG does not have the same painful history of slavery as the Caribbean and the woman known in Tok Pisin Creole as "Missis Kwin" remained popular there to the end.

"As other countries might look at departing from the Commonwealth or having the Queen as its head of state, Papua New Guinea is looking in the opposite direction in embracing what we have and making it bigger and better than it was before," said PNG Minister for National Events Justin Tkatchenko.

Empire gone, union may be next

But there are more clouds than bright spots on the horizon for what remains of the British Empire.

Within five years, Papua New Guinea may be the only predominantly non-white nation with more than a million people that still recognizes a British monarch as head of state.

The next frontier of imperial disintegration is likely to be closer to home.

Scotland may well see a new independence referendum. In an apparent effort to make the break seem less radical, Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has proposed keeping the Queen as head of state. But few believe the Scottish Nationalist Party is really committed to monarchical government.

In any case, the dissolution of the United Kingdom would be a blow to the Royal Family that united it in 1707, and would open the door to new uncertainties.

And demographic change in Northern Ireland looks likely to reopen a much more dangerous debate in which the Crown's continued role would very much be at stake. Irish republicans have shown respect regarding the Queen's death but, unlike the Scots, they could never accept a continued role for her family.

The British Empire has been winding down for a hundred years. The process clearly is not yet finished.