Review: Uta Barth's fuzzy photographs come into stirring focus in a major Getty show

In the 1960s, artist Robert Irwin famously forbade publication of photographs of his paintings — the spare abstractions of colored lines against colored fields, the tiny dots covering slightly bowed canvases to create a cloud of hazy gray atmosphere and the plastic or aluminum discs that stand out from the wall but visually appear as orbs that hover in space, like mysterious floating eyeballs.

When his terrific 1993 retrospective exhibition opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art and the photo ban no longer made sense, finally he relented. Irwin’s revolutionary work, dubbed an art of Light and Space, was by then established. But the three-decade photo prohibition had served to make a critical point: A camera could record the image within a work of art, but a photograph of it could not embody the sense of presence great art produced — and that Irwin’s rigorously conceived and executed work demanded.

Experiencing the art itself was the only way to discover its complex perceptual elucidation. A photograph was a misrepresentation.

Around the time that Irwin lifted the ban, German-born American artist Uta Barth was making her own extraordinary discoveries. She had encountered Irwin while a UCLA graduate student, and she was deeply moved by “Seeing is forgetting the name of the thing one sees,” Lawrence Weschler’s landmark 1982 book about the unprecedented older artist. Profound perception begins to happen, as the title astutely observes, when preconceptions dissolve.

Something extraordinary began to happen in the photographs Barth was making — art that is the subject of another powerful retrospective exhibition, “Uta Barth: Peripheral Vision,” just now winding up its run at the J. Paul Getty Museum (it closes Feb. 19). Her exceptional art’s hallmark is its sense of presence that unfolds perceptual knowledge. The camera, it turns out, is itself a quintessential medium for making its own art of Light and Space.

Take “Ground #41” from 1994, a now-classic example. Just under a foot on each side, the frame is filled by an image of shelving lined with books. All of it is out of focus, from edge to edge. You find yourself straining to see, even though the exercise of deciphering what the texts might be is bound to fail. The fuzziness breaks the first rule of photography: Focus, please.

The more you look, though, the more things do converge into something that approaches unexpected clarity. Yes, the image is out of focus, but it dawns that it’s the kind of view one expects as the background of, say, a figure study or portrait. You sense the missing person. The only people present in this picture are the photographer and you. Strange intimacy unfurls.

Barth indeed made the photograph by focusing on a person standing before the camera in sharp delineation, then having the person leave the scene. A focal plane had been established. The spatial distance between the camera and the soon-to-be-missing subject was carefully set. The shutter snapped, and meticulously calibrated light entered the camera lens to land on the waiting film. An image was created.

In short: Light and space are the two fundamental elements that make any photograph. Everything else is, well, everything else. Which is not to say all the rest is unimportant — anything but.

Those books, for example. Books are repositories of defined knowledge. Showing packed shelves celebrates that, while fuzzing the books to make them unreadable also dissolves any preconceptions they contain. Words are one valuable type of language, pictures are another.

Looking at Barth’s “Ground #41” makes me think of the late L.A. Conceptual artist John Baldessari. “Wrong,” his pivotal 1967 painting, is a black-and-white self-portrait photograph printed on canvas. The faulty composition cited by the title shows the artist in a sunny suburban front yard, rather than a gritty urban loft where artists supposedly thrive. He’s standing in front of a palm tree that absurdly appears to be growing straight out of his head.

For art, that’s all just wrong.

This sort of conceptual art is integral to Barth’s practice. Making a completely out-of-focus photograph, as she did, is likewise as wrong as it gets — at least as far as the usual standards of camerawork go.

The photograph’s composition reveals itself as similarly fascinating. Rather than one bookcase, Barth included two, abutted side by side. The dark brown furniture’s vivid horizontal and vertical lines compose a two-dimensional grid that’s slightly off-center.

The design and its syncopation of colored book spines recall any number of familiar geometric abstract paintings, like those by Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian from a century ago; or abstract weavings by Sophie Taeuber-Arp in the 1910s that upended the traditional artistic primacy of painting; and canvases by John McLaughlin, Ellsworth Kelly and Barth’s countryman Gerhard Richter from the 1950s and ’60s. The history of modern abstract painting and its often anxious relationships to both the material world and photography is embedded in Barth’s work.

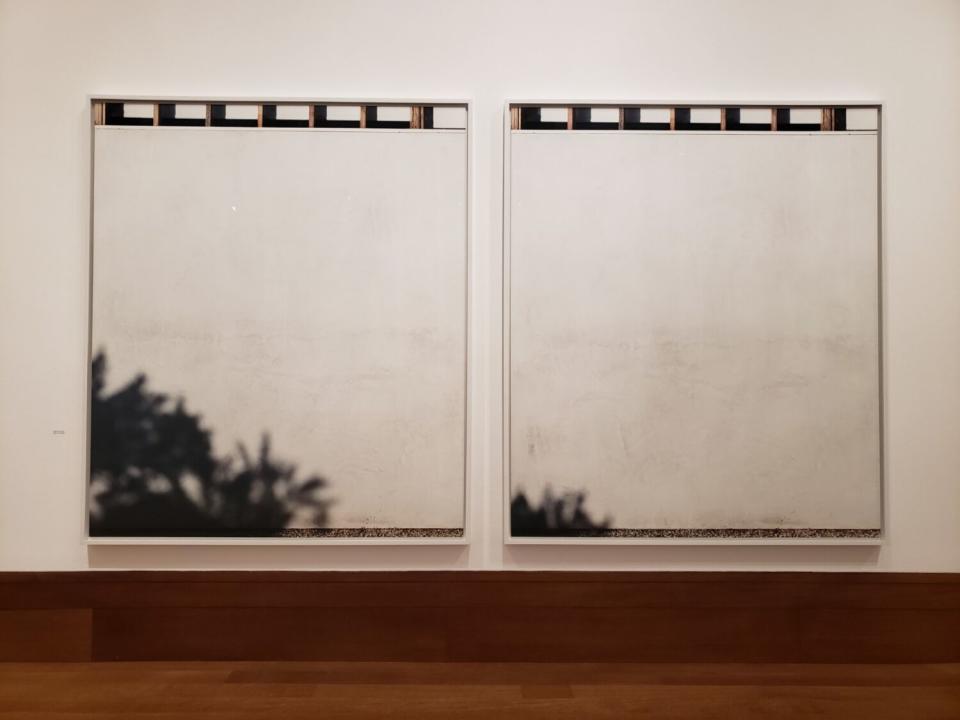

Other photographs with crisp close-ups of the drawers and doors of all-white cabinetry further engage the rectilinear structure of Malevich and Mondrian paintings, as well as those of Robert Ryman, whose white-on-white abstractions pare down painting into endless permutations of the basic elements of white paint applied to a flat surface affixed to a wall. Recent Barth still-life pictures of vessels on a tabletop refract the light, holding it within volumes while you remember the clusters of bottles and bowls in the paintings of Giorgio Morandi.

Even Jackson Pollock turns up — in a wholly unexpected place. A quartet of large horizontal photographs, titled “… and to draw a bright white line with light,” presents a ribbon of illumination that flows across sheer curtains in the artist’s living room. The glowing band of luminosity makes a disembodied linear drawing in space.

The radical liberation of painting achieved by Pollock in the late 1940s came from what would prove to be his hugely influential technique of “drawing in space,” which the artist performed with a paint-loaded brush hovering above a canvas spread out on the floor. Where the paint fell from his brush to the canvas below became the work of art; the drip paintings are a communion of natural happenstance and precise artistic control.

In a witty move, one Barth picture in the group includes a glimpse of her own hand reaching in to manipulate the curtain and artfully arrange the shape made by the elastic line of light. It’s one of the few times a human body part turns up among the 60 mature pictures in “Peripheral Vision,” which surveys the past three decades of her work. (Getty curator Arpad Kovacs smartly included an enlightening separate gallery of student work in which Barth, now 64, experiments with photographs of her body.) Not only is she the wizard behind the curtain pulling the levers of what we see, like some imaginative earthbound magician stranded in a fantastical Oz, but the hand of the artist, flaunted in considerations of painting but rarely in photographs, is dutifully acknowledged.

The show’s one disappointment is that almost all the photographs are roped off by wire stanchions erected low to the floor. (I think of them as tripwires.) They line room after room. Talk about drawing in space! It’s a visual annoyance, especially for an art so visually acute.

No doubt the decision resulted from concern about protecting the work’s pristine surfaces. Barth's pictures are almost never framed behind glass, as most art museum photographs are. Barth typically mounts her prints on wood panels a few inches deep, emphasizing their reality as physical objects. They’re not merely images of other things but are things in their own right — more like paintings than conventional photographs.

It’s a relief to come upon an extraordinary group of roughly life-size pictures of light falling across the exterior stucco wall of Barth's home studio. These monumental photographs, each more than 6 feet tall, are framed behind glass, so installed without the intrusive stanchions.

The artist’s affiliation with the Getty dates to 2000, when she was among 11 artists commissioned to make work related to the museum’s collection for “Departures,” a marvelous 10th-anniversary exhibition. Keying off Claude Monet’s light-drenched painting of snow on a field of Giverny haystacks, the first series in which the Impressionist artist concentrated on the shifting illumination of a single subject, Barth produced a gorgeous series of pictures of light moving across her living room wall above the top edge of a sofa. Their luminous display of fluid yellow hues is suitable for the Golden State.

They’re also quietly humorous. A wobbly luminous rectangle sliding across the wall is art to hang over the sofa.

Household subjects are Barth’s stock in trade. Like the bookcase, curtain, cabinetry or studio wall photographs, these living-room sofa pictures underscore how close to home almost all her chosen images are. Brilliant Light and Space art does not require a mythologizing retreat into the remote desert to drop a couple hundred million dollars into tearing up an extinct volcano to produce revelatory perceptual knowledge, as James Turrell’s "Roden Crater" project presumes to do. Domestic experience is rich and fruitful.

Speaking of which, the emergence of the Light and Space movement in the 1960s marked the simultaneous rise of Los Angeles as a distinctive cultural wellspring — the first suburban art world, neither densely urban nor remotely rural. There really hadn’t been anything like it in the annals of modern art before.

Where did this new, revelatory ethos come from? Usually, its concurrence with the socially spooked, post-Sputnik rise of the aerospace industry in late '50s and early '60s Southern California is offered as explanation. Public and private experiment in the Cold War’s suddenly urgent “space race” was rapidly opening up new perceptions of the world and its place in the expanding universe — including inquisitiveness about the nature of perception itself.

Amid such inquiries, art and an embrace of new materials formed a natural spinoff. Translucent sculptural objects and atmospheric environments engaged a viewer’s participatory perception, often through the use of industrial materials like fiberglass, acrylic, neon and polyester resin.

Certainly, there is truth to that. But, culturally speaking, it may be a lesser factor. The absorbing Getty retrospective, in addition to cementing Barth’s artistic reputation, has made me wonder whether it isn’t the post-World War II saturation of camera vision newly dominating daily American life that created the dynamic that gave birth to Light and Space art — one that would surely be felt most intuitively in the lens-driven movie and television capital of the world.

The ubiquitous camera operates as the machinery of light and space, churning out daily perceptual experience that we all share. Barth, brilliantly unraveling its myriad mysteries, is the shrewd and savvy photographer of Light and Space.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.