SLO climbing gym’s employees can’t afford to live in the city — and neither can its owner

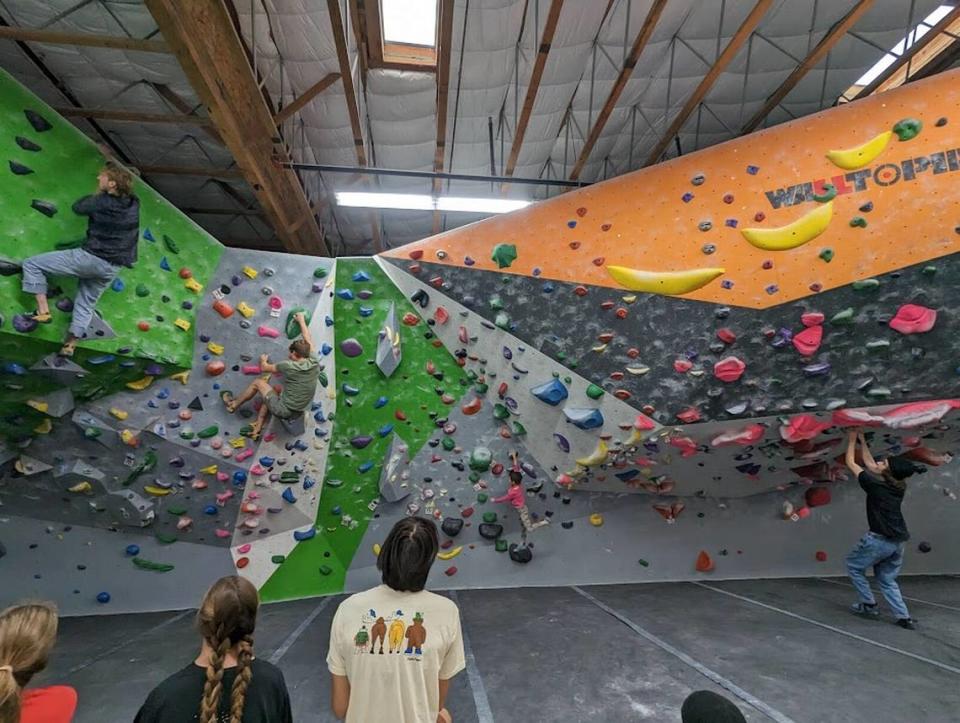

The Pad Climbing gym has been a fixture in San Luis Obispo’s rock climbing scene for the past two decades, but according to owner Kristin Tara Horowitz, running the gym has been anything but an easy trek.

An avid climber, Horowitz translated her love of the sport into the foundation of her business, which is currently San Luis Obispo County’s only dedicated climbing gym.

However, despite that passion, Horowitz said she is rarely able to enjoy the benefits of owning her own climbing gym.

Horowitz said she and her employees are experiencing the same problem as many other San Luis Obispo County businesses: Almost none of her employees can afford to live near their place of work, or, in some cases, meet the high costs of living synonymous with San Luis Obispo County.

In Horowitz’s case, it’s been more than two months since she last set foot in her gym, much less actually had the chance to scale one of its many walls and climbing surfaces.

“It is sad — I really thought I would be a good climber and I would know everybody in the community, and I barely know my employees,” Horowitz told The Tribune in an interview on May 11. “I barely know the people that haven’t been here for a long time. I just don’t have the ability to stay in a relationship and also run my family and also do my job.”

Long commutes hurt ability to form community, SLO gym owner says

Horowitz said 2022 was the first profitable year in The Pad’s history, largely because the gym started as a nonprofit for its first 15 years of existence.

Originally founded in 2002 by Horowitz’s husband, Yishai Horowitz and co-founders Paul Hatalsky and Julie Workman as SLO-Op, a co-operative nonprofit bouldering gym, the business went for-profit under The Pad name in 2017, according to its website.

The business’ San Luis Obispo location at 888 Ricardo Court has been open since then, and is the only one of its kind in the county, Horowitz said.

The Pad operates three gyms, located in San Luis Obispo; Henderson, Nevada; and two locations under a single gym umbrella in Santa Barbara, with a staff of around 35 employees per gym that operate them 24 hours a day, seven days a week, Horowitz said.

Unable to find housing near their business in San Luis Obispo, Horowitz said she and her husband were forced to look to neighboring cities to find the most affordable homes available.

In the decade since the couple bought their Los Osos home — a 1,000 square-foot house originally built in 1972 as a People’s Self-Help Housing low-income unit — Horowitz said she’s seen the cost of living rise “dramatically” in San Luis Obispo.

She and her husband “couldn’t believe (they) could afford it,” and only qualified for the home with a U.S. Department of Agriculture rural housing loan, she said.

However, owning a home effectively locked them into living in Los Osos long term, a situation that became more untenable the longer they lived there.

“I have small children,” Horowitz said. “I have no free time to go enjoy myself in my own gym anymore. I can’t work out here, I can’t climb here, because it’s an hour round trip.”

Horowitz said it’s now more expensive to live out of San Luis Obispo than it is to live in the city, and even with her home’s value doubling over the years she’s lived there, flipping her Los Osos house still wouldn’t give her enough to move her family closer to the gym.

Though Horowitz owns the business and works as its CEO, she and the company’s higher-ups don’t make much more than the gym staff, the majority of whom work on minimum wage, she said.

“We’ve intentionally not taken large salaries, No. 1 to make sure that we survive everything, but two, I want to stay tied to my employees and be in a certain peer group, so that I’m never making too much more than my employees are,” Horowitz said.

High cost of living makes retaining climbing gym employees hard

At one point, Horowitz said, the challenge became so severe she considered buying employee housing for her workers.

“We looked at trying to buy a property that was deed-restricted to employee housing,” Horowitz said. “But the employees don’t want that because they don’t want their employment having to be tied to their housing, which makes sense — no matter how benevolent an owner you want to be, you’re still going to be someone’s landlord.”

Since the gym reopened in the years following the COVID-19 pandemic, Horowitz said the majority of her full-time employees live with their families and roommates.

Most live in subpar rentals in the area, while other groups of employees live together to keep prices down, she said.

In some of the more extreme cases, Horowitz said she’s had employees temporarily living in The Pad’s driveway and inside the gym when they were between homes.

That briefly worked because of The Pad’s round-the clock access, showers and restrooms, but was not a sustainable living situation, Horowitz said.

“I’ve had three full-time employees move in the last two years out of state so that they could afford to buy a place,” Horowitz said. “The majority of my full-time employees that are still here live with their families or with roommates.”

Heidi Gue, 19, moved to the San Luis Obispo area with her family around two years ago from Kentucky, and currently works at The Pad on its gym staff.

Gue said she still lives with her parents, but not by choice. Despite working two jobs before eventually going full-time at The Pad, Gue said she’s only now able to move out of her parents’ home.

“I remember when you found out that I had a second job and you were like, ‘Oh, I didn’t know that,’” Gue said to Horowitz. “I could see it in your face that you were a little disappointed that I had to work two different jobs.”

More housing solutions needed to alleviate problems, owner says

Horowitz said she isn’t the first business owner to face employee housing issues, and won’t be the last.

Though Horowitz said she applauds the city and county of San Luis Obispo’s current efforts to make housing more abundant and affordable, there won’t be much relief for business owners and their employees’ housing problems until local governments take “bigger risks” in addressing the issue.

“The quality of life here will start to degrade the more expensive it gets if we don’t allow people who serve us to live here,” Horowitz said. “That is the No. 1 problem.”

At the very least, if the city and county government want to keep their citizens invested in local businesses and amenities, it’s necessary to add more incentives to build workforce housing, Horowitz said.

More incentives for remote work might also help alleviate housing problems, she said; because her business’ non-gym staff all work remotely, they don’t occupy any office space. Those now-vacant office buildings and the land they sit on could be a candidate for reuse as housing, she said.

Expansions of the city’s transit system — specifically its bus lines within town and between others areas of the county — would lower the number of car-dependent residents, allowing for parking spaces to be reclaimed as housing lots, Horowitz said.

A less car-dependent San Luis Obispo would also mean employees who are still boxed out of living in the immediate area would face lower transportation costs while the housing to support them grows, Horowitz said.

Despite San Luis Obispo’s cost-of-living problems, Gue said the skills learned and experience gained by working in a good company culture will help her long-term.

“I think that the fact that it is so expensive here will definitely drive a lot of people away,” Gue said, “but I don’t think people ever want to leave.”