N.B. chronic absenteeism numbers are high — but one district sees promising improvement

The problem of chronic absenteeism in schools is growing, according to a document released by the province earlier this week.

And it's an issue that the Anglophone North School District has been trying to urgently address.

"Last July and August, when we kind of looked back at our absenteeism, we were hitting about 48-per-cent chronic absenteeism," said district superintendent Dean Mutch.

That percentage isn't far off from the rest of the province, which is why Mutch said he was not surprised to see the numbers released by the government.

Dean Mutch, Anglophone North superintendent, said his plan targeted kids who were missing school without reason. (Kim Harris Photography/Submitted by Dean Mutch)

An action plan released Tuesday aimed at addressing issues in the anglophone education system said in the 2022-2023 school year, just over 37 per cent of New Brunswick children in kindergarten to Grade 5 were chronically absent.

That number increases to 45 per cent for middle and high school.

According to the document, chronic absenteeism is when a child misses more than 10 per cent of scheduled school days, approximately equivalent to four weeks over the school year.

We understand kids get sick, we understand there's hospital appointments, all that. But it was a group of kids that we couldn't put our thumb on— why are they missing school? - Dean Mutch, superintendent, Anglophone North School District

The plan says an absence intervention model will be developed to help schools respond to children who are "identified as at-risk for increased absences."

But Mutch has already been doing something similar in Anglophone North.

He said they developed a plan in August, which was introduced to staff and teachers and agreed upon.

Since implementing that plan, he said chronic absenteeism in his district has dropped to around 29-30 per cent from 48 per cent.

The plan

Mutch said the plan targeted kids who were missing school without reason.

"We understand kids get sick, we understand there's hospital appointments, all that," he said. "But it was a group of kids that we couldn't put our thumb on — why are they missing school?"

The plan required teachers to call the child's home after five missed days, not necessarily consecutive, to see if something was going on and if there was anything they could do to help.

At 10 missed days, the principal made the same call and might suggest a meeting with the parent.

After 15 days, he said the discussions would become a bit more serious.

Mutch said the calls were to establish a relationship with the schools, to say to parents, 'We want your child in school. We want to bring them back, what can we do?' So once they kind of got that, they understood what I was trying to do."

He said in late fall, when flu season hit, there was some concern from parents that they had to send their children to school "or else I'm going to get a phone call."

Mutch said it was important to explain that if children are sick it's OK to keep them home.

"The key to it was my staff — I cannot say that enough," said Mutch. "The teachers, I asked them to do this back in August. I stood in front of them on opening day, I said 'This is my one ask.'"

When the school year finishes in June, Mutch said he will take a look at the data gathered and see what worked and what didn't.

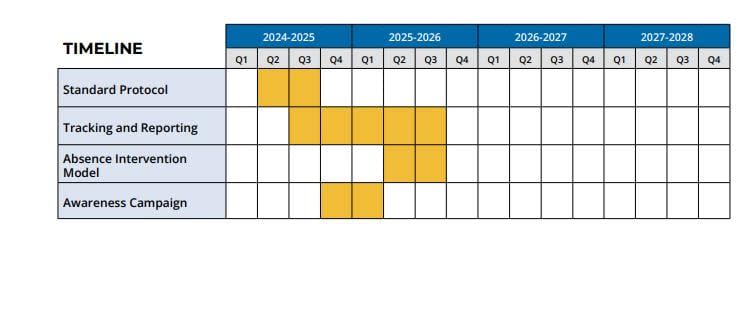

A chart from the province outlines the timeline for a plan aimed at addressing chronic absenteeism in the anglophone education system. (Government of New Brunswick)

But overall, he's happy with the program, his staff and the parents of the students.

Mutch said he thinks this plan was especially important, but not not just because kids are missing out on crucial lessons and assignments.

"It's not just about coming to school and learning, it's coming to school to see your friends, hanging out, getting to know how to act around other people," he said.

"It's that area that I really want kids in school for."