Biden can control Trump's security clearance -- for now

Former President Donald Trump is the presumptive Republican presidential nominee. He is also now a convicted felon, a New York state judgment that concerns a hush money conspiracy before he became president.

Normally, a major party nominee gets access to highly classified information, including a version of the President's Daily Brief on intelligence. A president-elect gets even more. And the sitting president has more access and authority over the nation's secrets than anyone else.

A criminal conviction, however, normally disqualifies someone from a security clearance -- a license to read documents marked "SECRET" or "TOP SECRET."

So what to do about a nominee who is also a felon -- who may get elected?

As a law professor who teaches and writes about secrecy and who earlier in my career handled classified information while working for the U.S. intelligence community and a U.S. Senate committee, I would never have expected this dilemma.

The good news is that the law has several clear answers.

Presidents get access to classified information because of the office they hold, not because they meet criteria in executive orders and administrative rules. The president technically does not even have a clearance. Practically and legally speaking, the president also sits at the apex of the executive branch's massive secrecy apparatus. So if Trump is reelected, he would have expansive access to classified information and control over it. And control over secrets and clearances available to others.

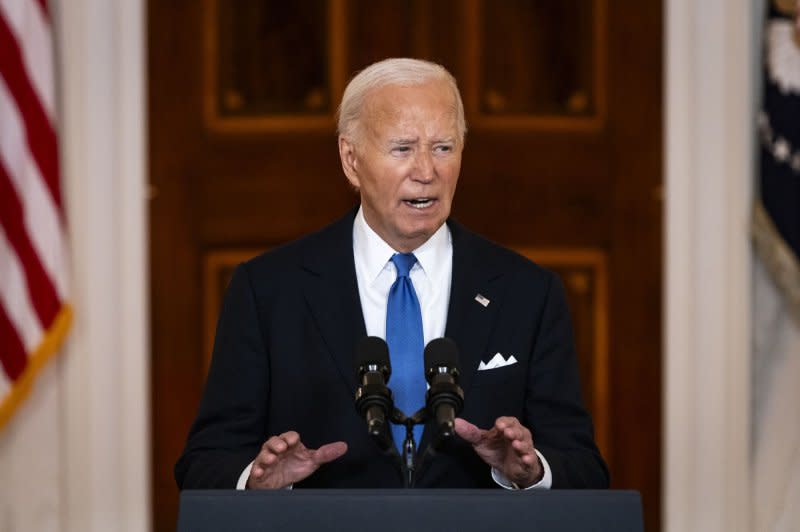

Joseph R. Biden is the current president, and therefore legally he decides whether his opponent gets the usual access to classified information.

Ultimately, whether Trump's 34 felony convictions and other questionable conduct disqualify him from classified information access is identical to the question before voters: Should Trump again be president?

The U.S. secrecy system

Most U.S. government employees and contractors do not have a security clearance. If their record suggests trustworthiness, those with a "need to know" can receive this license to access the several levels of classified information, called "Confidential," "Secret" and "Top Secret."

Federal investigators carefully screen applicants for national security positions and security clearances. To assess a candidate's trustworthiness, investigators interview the candidate, review their filings and search databases. Some investigations involve a polygraph of the candidate and interviews of people they know. Once a clearance is granted, investigators continue to monitor clearance holders.

Key factors the investigators consider include loyalty to the United States, respect for rules and the rule of law, psychological stability, good judgment and good character in terms of trustworthiness and integrity. Substance abuse, marital infidelity or financial problems can suggest poor judgment and vulnerability to blackmail or other kinds of coercion.

The president's broad power

The president oversees the country's entire national security secrecy system. The president has the authority to read all classified documents, to classify and declassify almost any piece of information and to oversee the security clearance system. There is no other government official who decides whether the president should have access to the nation's secrets.

The Supreme Court has held that authority over classification and clearances flows in part from the power the Constitution gives the president. In a dangerous international security environment, the president needs to be able to know secret information about foreign threats, communicate confidentially with foreign colleagues and subordinates and act with what Alexander Hamilton called in the Federalist Papers "secrecy, and dispatch."

Like the president, members of Congress get access to classified information by virtue of election, not by going through the regular security clearance process.

The dilemma is obvious: Trump is running to lead a national security enterprise that surely would have denied him a security clearance if he had to follow the rules that apply to his former and potential future subordinates.

If someone has a criminal conviction or a civil judgment involving fraud, they generally cannot get clearance. Such court rulings suggest problems following rules, which are integral to protecting classified information, plus disrespect for the law and dishonesty.

I cannot imagine any reasonable background investigator would see past the staggering evidence against Trump in this regard.

Under the "SMICE" rubric, for example, Trump is all red flags. SMICE stands for sex, money, ideology, crime and contraband, and ego.

First, there is extensive evidence that Trump committed sexual misconduct. Trump's 34 felony counts were connected to his hush money payments to a porn star with whom Trump had sex in 2008 while his current wife was pregnant.

Even marital infidelity on its own can endanger a clearance, because it suggests disloyalty and deception. It creates a dirty secret, creating risk of blackmail.

Trump's infidelity to all three of his wives is well documented. In 2005, Trump bragged on tape about his sexual assaults, saying that he will "just start kissing" women without consent, knowing that "when you are famous they let you do anything." Last year, the writer E. Jean Carroll won a civil judgment against Trump for raping her in the 1980s.

Second, one of the most common reasons for clearance denial or suspension is credit card debt or other financial problems. They create a motive for taking bribes or doing business deals in exchange for leaking secrets or other disloyalty.

Trump's businesses have recorded six bankruptcies. The fraud judgment immediately put Trump's finances again in jeopardy. There is considerable evidence that his business finances are linked with foreign governments, particularly Russia.

Third, Trump also has extreme ideological views. Trump has told violent militias to "stand back and stand by." The U.S. House Jan. 6 committee found in 2022 that Trump was part of a "multi-part conspiracy" to overturn the lawful results of the 2020 presidential election, an effort that included the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Trump also allegedly retained thousands of pages of classified documents after the end of his term in office -- at which point his authority to have them expired. He also opposed lawful government efforts to retrieve them.

Trump's record still matters

If he were treated like everyone else, Trump would never get a clearance. But the voters could restore his classified information authorities by returning him to the White House.

The ocean of red flags in Trump's record could still matter in two ways.

One is that, on that basis, Biden could break with tradition and not allow Trump as a major-party nominee to get intelligence briefings during the campaign or as president-elect.

And Trump's criminal conviction, plus other evidence of his lack of trustworthiness and commitment to the rule of law, could inform voters when they head to the polls.

Dakota Rudesill is an associate professor law and senior faculty fellow at Mershon Center for International Security Studies at The Ohio State University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.